Giant Family Tree of 13 Million People Just Created

The researchers, who sifted through 86 million profiles of people on the public genealogy site Geni.com, were interested in how human migrations and marriage choices had changed over the past 500 years.

"Through the hard work of many genealogists curious about their family history, we crowdsourced an enormous family tree — and boom — came up with something unique," the study's senior author, Yaniv Erlich, a computer scientist at Columbia University, said in a statement. Erlich is also the chief science officer of MyHeritage, a genealogy and DNA testing company that owns Geni.com, the platform that hosts the data used in the study. [Genetics by the Numbers — 10 Tantalizing Tales]

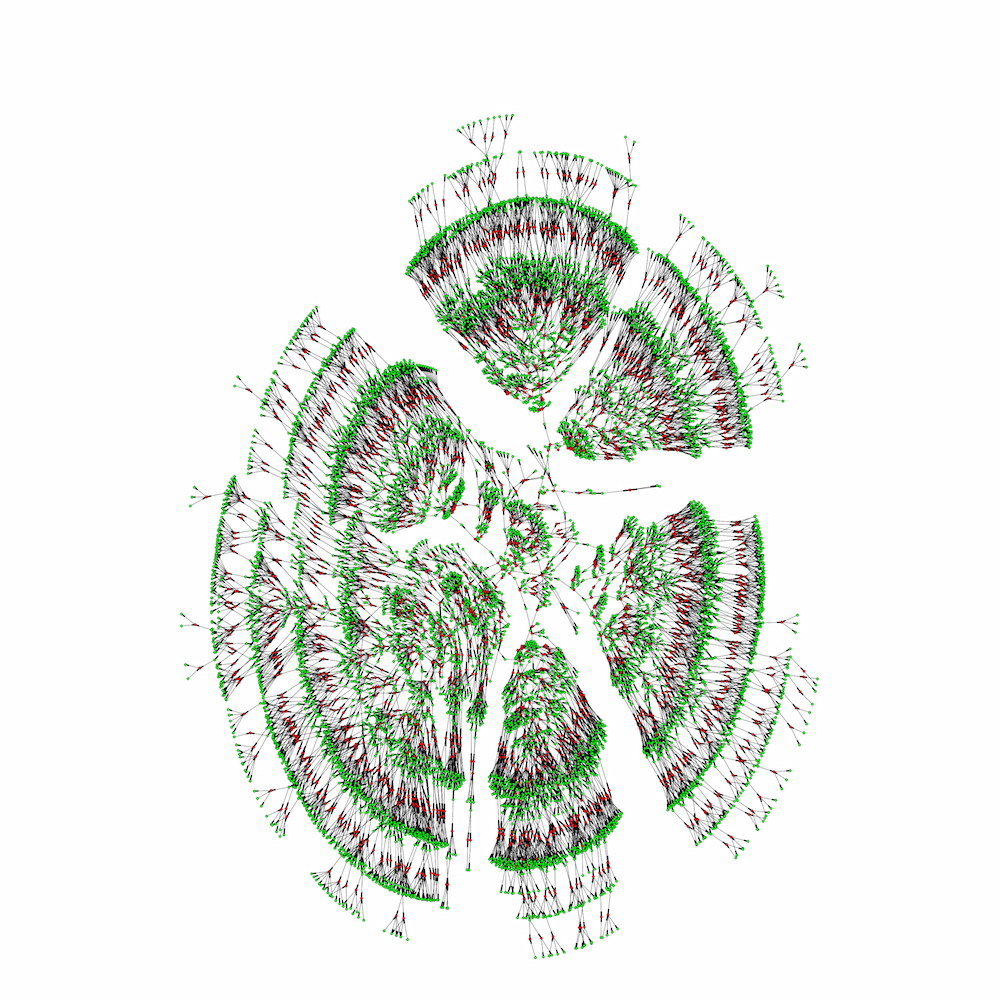

Budding tree

After downloading the 86 million profiles, the researchers used mathematical graph theory to organize and double-check the accuracy of the information. In addition to smaller family trees, they put together the giant one of 13 million people, connected by ancestry and marriage, spanning an average of 11 generations. If the data had gone back another 65 generations, the researchers could have identified the group's common ancestor and completed the tree, the researchers noted.

To confirm that the Geni data was representative of the general U.S. population, the researchers compared the Geni profiles with about 80,000 publicly available death certificates of people from Vermont, from 1985 to 2010. Overall, the two data sets had highly similar socio-demographics — meaning that the Geni-made family tree was a good representation of people in the United States, the researchers said.

The tree is, "to my knowledge, by far the largest set of families to date," Mark Stoneking, a professor of biological anthropology at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. This study shows "the power of leveraging personal ancestry data to get all sorts of novel information, [which] nobody really thought of before," Stoneking added.

Marriage mysteries

The newly created family tree shows that as times changed, so did the distance people traveled to find a marriage partner. Before 1750, most people in the United States married someone who lived within 6 miles (10 kilometers) of their own birthplace. But 200 years later, people born in 1950 tended to travel farther to find that perfect someone — on average tying the knot with someone who lived about 60 miles (100 km) from where both of the spouses were born, the researchers found.

"It became harder to find the love of your life," Erlich joked.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moreover, between 1650 and 1850, it was common for fourth cousins to marry. Nowadays, it's culturally taboo in the U.S. to marry someone so closely related to you, which may explain why marrying seventh cousins is more common today, the researchers said.

The family tree also revealed this curious tidbit: From 1800 to 1850, even though people traveled farther than usual to find a partner — almost 12 miles (19 km) on average — they were still more likely to wed someone who was a fourth cousin or closer, than it was for them to marry a more distant relative, the researchers discovered. This debunks the idea that when people travel greater distances, they say "I do" to people who are less related to them. [10 Wedding Traditions from Around the World]

Instead, it was likely changing social norms that prompted people to stop marrying their close relatives.

"We hypothesize that changes in 19th-century transportation were not the primary cause for decreased consanguinity," the researchers wrote in the study. "Rather, our results suggest that shifting cultural factors played a more important role in the recent reduction of genetic relatedness of couples in Western societies."

In addition, over the past 300 years, women in North America and Europe tended to migrate more than men did, the researchers found. However, when men migrated, they journeyed much farther, on average, than women did, the study authors found.

Life span decoded

The researchers took a gander at how genes influence longevity. They analyzed data from 3 million relatives born between 1600 and 1910 who had lived past the age of 30. This data set excluded twins, as well as people who died in the U.S. Civil War, World War I and World War II, or in a natural disaster.

Genes accounted for 16 percent of longevity variation, the researchers learned after comparing each person's life span to those of their relatives, as well as the degree of separation between such relatives. This is on the low end of previous estimates, which generally range from 15 percent to 30 percent, the researchers said.

The finding shows that people with good longevity genes may live an average of five years longer than people without those genes. But, "that's not a lot," Erlich said. "Previous studies have shown that smoking takes 10 years off of your life. That means some life choices could matter a lot more than genetics."

The 13-million-person family tree is available for academic research at FamiLinx.org, a website created by Erlich and his colleagues. The data on FamiLinx is anonymized (although, in 2014, Erlich noted that it's not terribly difficult to identify people in anonymous profiles, Live Science previously reported), but people can check Geni.com to see whether a family member has added them to the site. If you find yourself on Geni.com, there's a good chance you made it onto the giant family tree, the researchers said.

The study was published online today (March 1) in the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.