1.6-Billion-Year-Old Breath of Life Frozen in Stone

A nondescript series of pockmarks in rock is actually the captured breath of microbes from 1.6 billion years ago.

The fossils come from fossilized mats of microbes found in central India. Most of the microbes are cyanobacteria, according to new research published Jan. 30 in the journal Geobiology. These ancient microbes, among the oldest life on Earth, were photosynthesizers — like modern plants, cyanobacteria turned sunlight into energy, exhaling oxygen as a byproduct. Their ancient exhalations oxygenated Earth's atmosphere beginning around 2.4 billion years ago, paving the way for life as we know it today.

Cyanobacteria also excreted minerals that hardened into layered mats called stromatolites. Stromatolites are found in a few places today, notably Shark Bay in Western Australia and in a remote patch of freshwater in Tasmania, but they once dominated Earth's shallow seas. Swedish Museum of Natural History biogeologist Therese Sallstedt and her colleagues studied some of these mats from a thick sedimentary layer called the Vindhyan Supergroup, which may contain fossils of some of the oldest animal life on the planet. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

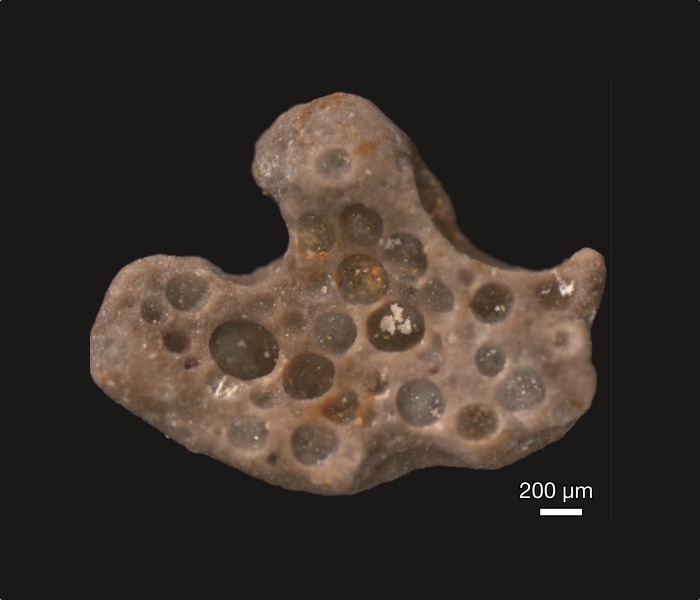

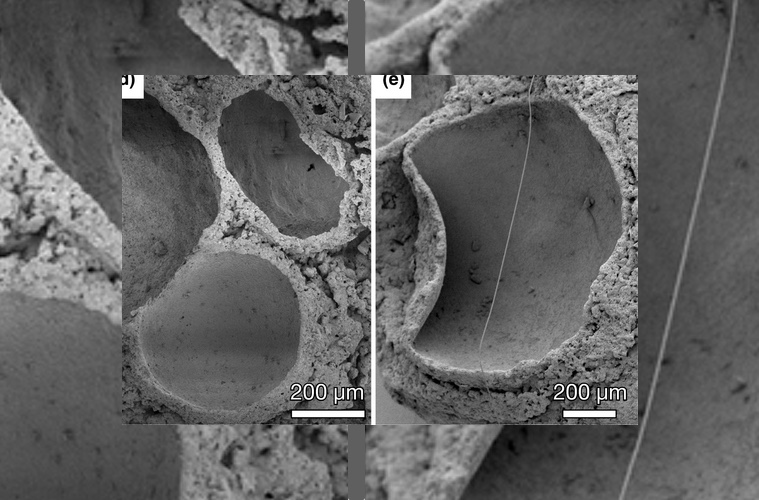

Amid the rock layers, the researchers found tiny spherical voids. Bubbles like this have been found before, the researchers wrote in their new paper, both in fossil microbial mats and in microbial mats that thrive today in hydrothermal water.

The bubbles are tiny, just 50 to 500 microns in size (for comparison, a human hair is about 50 microns in diameter). Some of the spheres are compressed, as if the once-flexible mats were squished before they became locked in stone. The mats also contain filament structures that are probably the remains of cyanobacteria, the researchers reported.

The bubbles indicate that the mats were filled with oxygen produced by the microbes inside, the researchers wrote. These particular stromatolites contain high levels of calcium phosphate, putting them in a category known as "phosphorites." The discovery of oxygen bubbles within these phosphorites suggests that cyanobacteria and other oxygen-producing microbes may have played a larger role than researchers realized in constructing this type of microbial mat in ancient shallow oceans, Sallstedt and her colleagues wrote.

Original article on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.