Bizarre, Parasitic 'Fairy Lantern' Reappears in the Rainforest After 151 Years

A strange plant that needs no sunlight and sucks on underground fungi for nutrients has turned up in Borneo, Malaysia, 151 years after it was first documented.

Thismia neptunis is what's called a "mycoheterotroph," meaning it's part of a group of plant species that has given up photosynthesis entirely, in favor of living as parasites. They grow no functional leaves and do most of the work they need to survive underground. T. neptunis is most easily identified by its sexual organ: a small, 3.5-inch (9 centimeters) flower it pokes out of the ground, that looks like it might belong on an alien planet or perhaps deep in the ocean.

Instead, it grows in the wet dirt of a rainforest alongside a river in an area called Matang massif. [Gallery: Scientists at the Ends of the Earth]

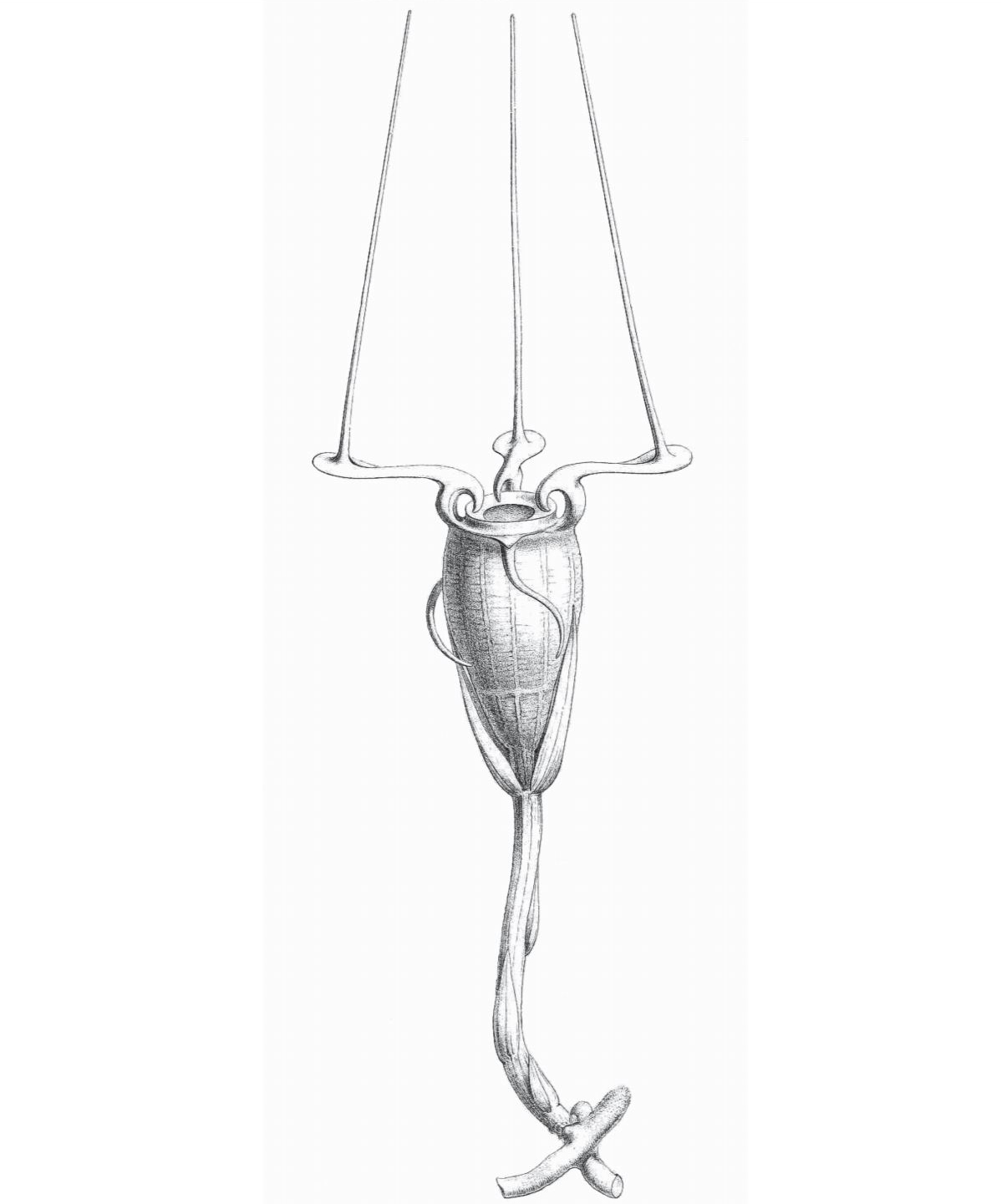

The Italian botanist Odoardo Beccari first documented the little flowering weirdo in 1866, making beautiful drawings of its unusual shape that helped modern researchers identify specimens they found in the same region in 2017.

"To our knowledge, it is only the second finding of the species in total," the team of Czech researchers wrote in a paper published Feb. 21 in the journal Phytotaxa.

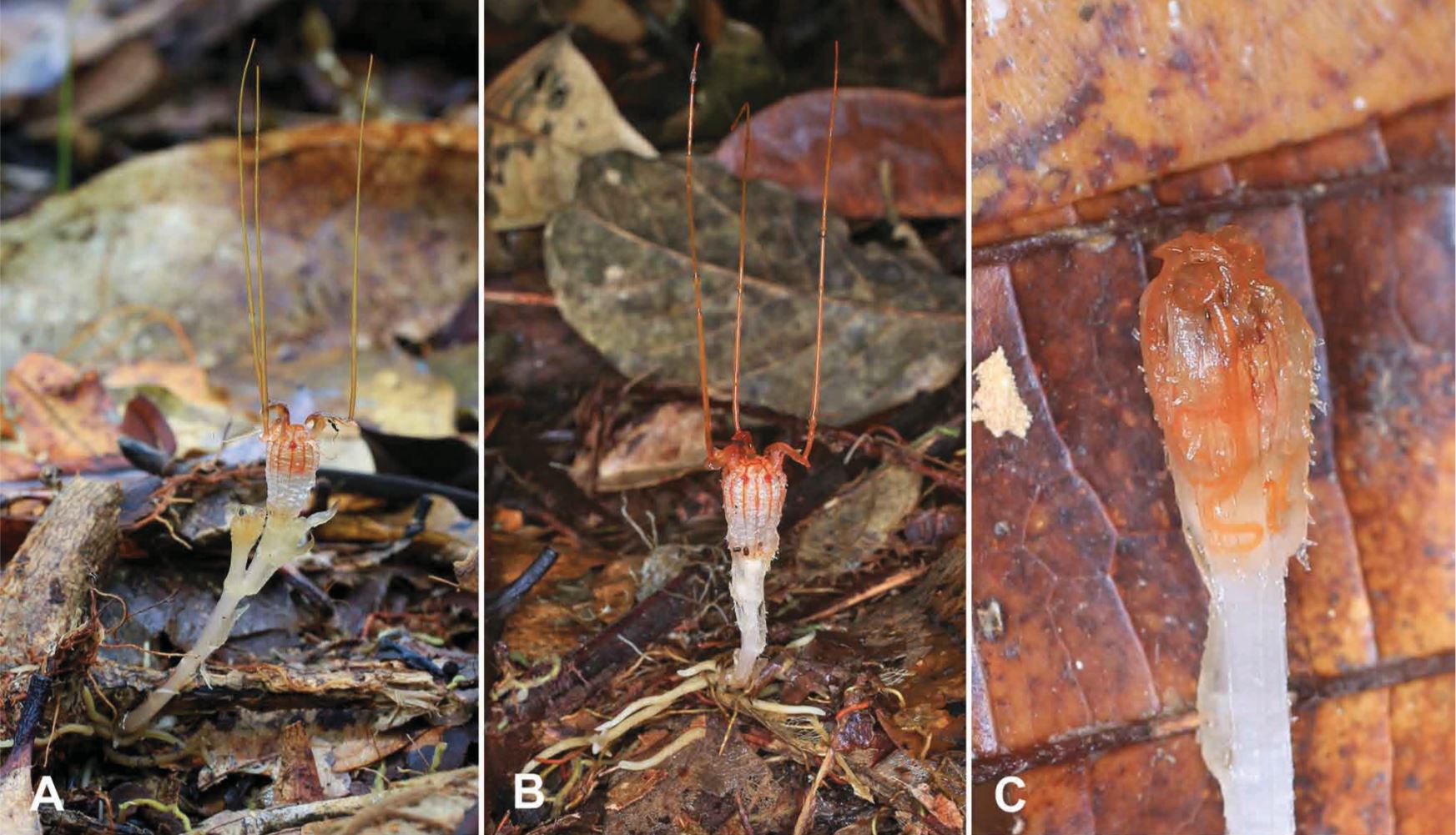

The flower is small enough to overlook, but strange once noticed. It belongs to the genus Thismia, a group of closely related plants colloquially referred to as "fairy lanterns." And the Czech team's photographs reveal that it looks remarkably similar to Beccari's original drawings.

Its smooth stem, "whitish or creamy," the researchers wrote, pokes up from a simple system of roots designed to goad nutrients from underground fungi. Its bulb has the shape of a bruised and swollen thumb — only it is sickly pale, striped with red, and has an opening at the tip like the mouth of a sea-worm. The most dramatic part of the flower is the trio of "red, hairy" appendages sticking straight up like a shrimp's long antennae from flat protrusions around the bulb — part of its pollen-producing organ.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers said they don't know precisely how the plant pollinates, but they did find two species of dead fly inside the flower, which they said might act as pollinators.

Mycoheterotrophs like T. neptunis are the gentler of the two sorts of parasitic plants that shun sunlight. The fungi they drink from do attach to nearby photosynthesizing plants, but the mycoheterotrophs don't invade those plants directly. That separates them from haustorial parasites, which sink hungry roots directly into the plants they live on, according to a fact sheetfrom botanists at Southern Illinois University[JB1] .

The researchers wrote that their rediscovery of T. neptunis is part of a broader pattern of biologists discovering new and long-lost species of plants in rainforests in the last decades, even as rainforests all around the world are shrinking and threatening collapse.

It's unknown, they wrote, the breadth of T. neptunis' range, or how that range has shifted since 1866. Beccari didn't leave detailed information on precisely where he found the flowers, though he was staying in a cabin near where the researchers spotted it recently.

The researchers wrote that the discovery makes them more hopeful that they might encounter two more plants Beccari described from his time in Malaysia that haven't been seen since, because the region of rainforest where he worked (and where T. neptunis was found) has remained largely undisturbed.

Originally published on Live Science.