This Is One of the Tiniest Ancient Birds, and It Lived Alongside Giant Dinosaurs

About 127 million years ago, tiny birds the size of grasshoppers lived alongside some of the biggest animals to walk the Earth, including the long-necked sauropods, a new study finds.

When it was alive, this less-than-2-inch-long (5 centimeters) chick would have weighed just 0.3 ounces (8.5 grams) — about the weight of one-fifth of a golf ball. That makes it one of the smallest birds from the dinosaur age on record, the researchers said.

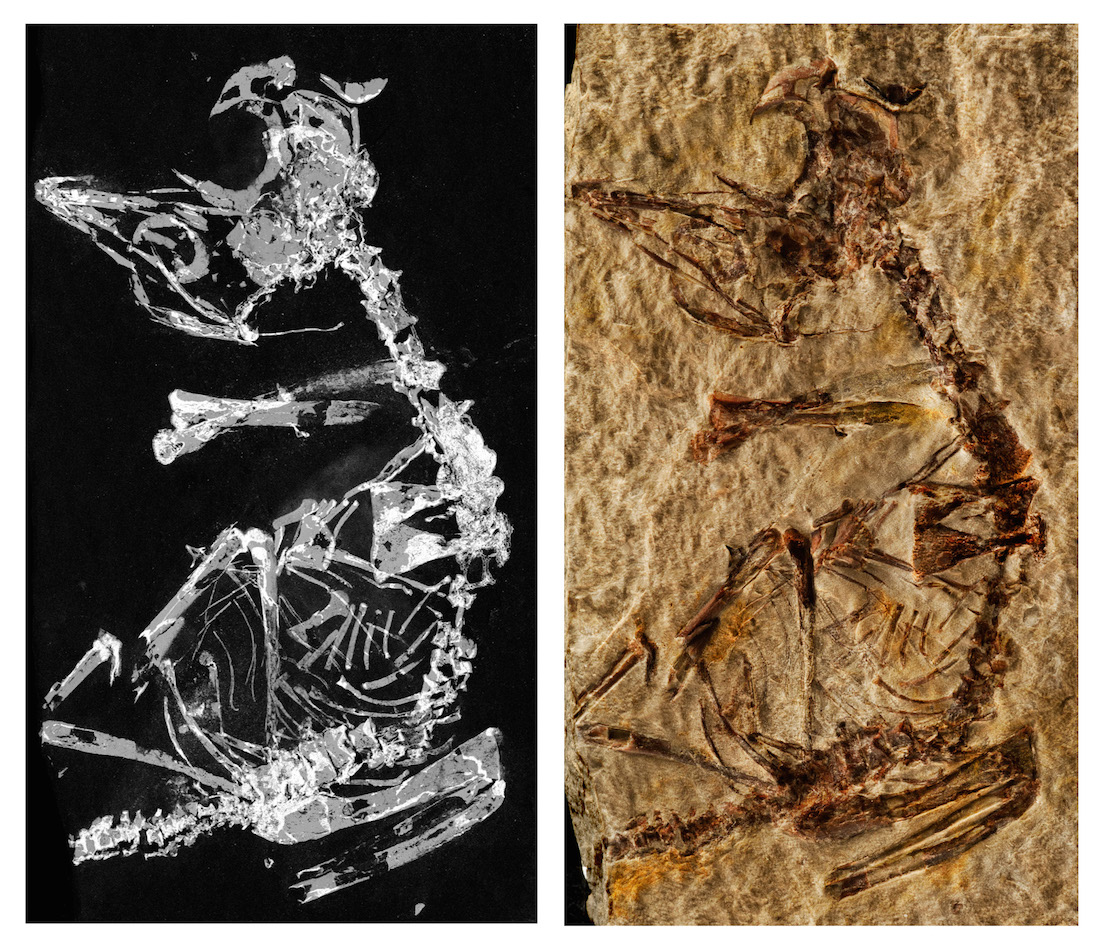

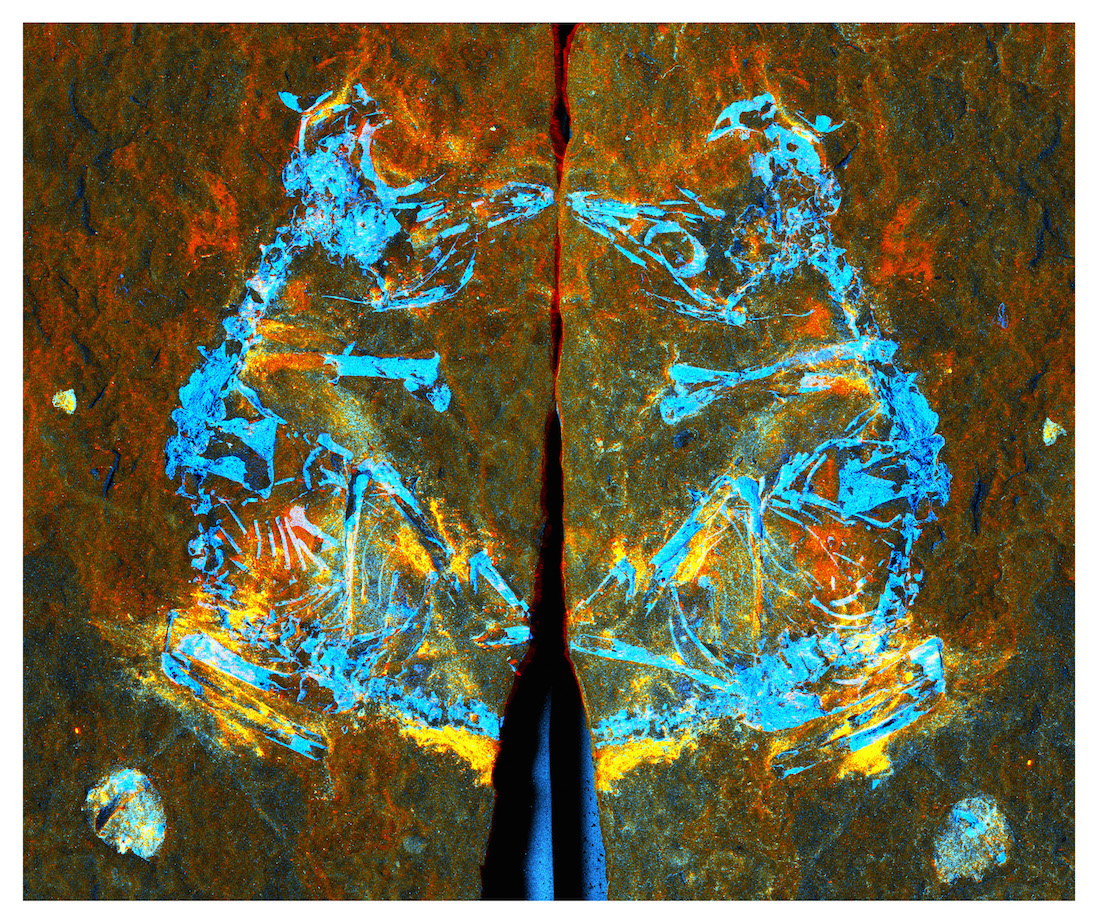

Nearly all of the little bird's fossilized skeleton had been preserved, making it a paleontological treasure that provides insight into how this bird's group —Enantiornithes, a now-extinct subclass of birds that tended to sport teeth and clawed fingers on their wings — grew after hatching from their eggs. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

It's still unclear whether the bird is a newfound species, or whether it belongs to a previously identified species, such as Concornis lacustris or Iberomesornis romerali, which are other enantiornithine birds found in the same location, the Las Hoyas fossil site in central Spain, the researchers said.

But the bird's lack of a name didn't stop researchers from studying it. The team members used synchrotron radiation to image the tiny specimen at the submicron level, they said. (A micron, or micrometer, is one-millionth of a meter. For comparison, a strand of human hair has a diameter of about 50 to 100 microns.)

"New technologies are offering paleontologists unprecedented capacities to investigate provocative fossils," study lead researcher Fabian Knoll, a paleontologist at the University of Manchester's Interdisciplinary Centre for Ancient Life and ARAID-Dinopolis, a paleontology museum in Spain, said in a statement from the University of Manchester.

The analysis revealed that the tiny bird died shortly after it hatched from its egg. In addition, the chick's sternum (the breastplate bone) hadn't yet developed into hard, solid bone, and it was still made mostly of cartilage, the researchers found. This means that the Cretaceous-period chick likely couldn't fly at the time it died, they said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moreover, the patterns of ossification (bone hardening) in the bird are quite different from those of other young enantiornithine birds discovered over the years, suggesting that the developmental strategies of these ancient avians was more diverse than previously thought, the researchers said.

But, although this newfound bird probably couldn't fly, it wasn't necessarily dependent on its parents for food and care, the researchers said. While some modern chicks are "altricial," meaning they need their parents' help, others, like the chicken, are "precocial," or mostly independent.

This tiny bird was hardly the only feathered creature scurrying about 120 million years ago. Fossil remains show that a water bird coughed up the first bird pellet on record at about this time. Furthermore, researchers have also found fossilized rods and cones in a bird's eye dating to about 120 million years ago, indicating that at least some ancient birds could possibly see in color, Live Science previously reported.

The new study about the tiny bird, which is now housed at the Museum of Paleontology of Castilla-La Mancha, in Cuenca, Spain, was published online today (March 5) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.