Man's 'Missing' Brain Was Actually a Large Air Pocket Inside His Head

Falls are a common problem among older adults, but for one 84-year-old man in Northern Ireland, a brain scan revealed a highly uncommon cause for his falls: A part of his brain appeared to be missing.

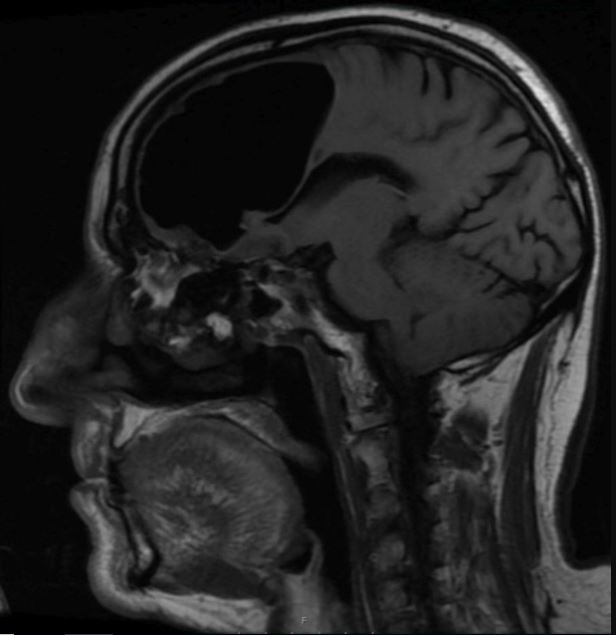

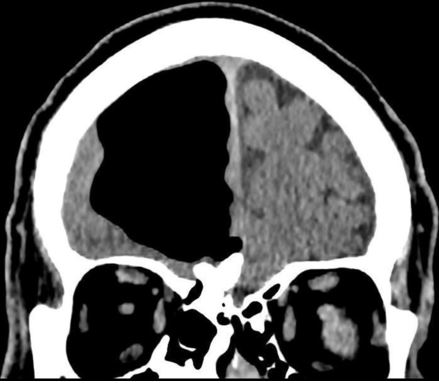

The stunning scan revealed a large, black space behind his forehead, where the front of his brain should have been.

His physician, Dr. Finlay Brown, a general practitioner in Belfast, first reviewed the brain scan while waiting to hear back from radiologists. (Typically, radiologists provide a report that accompanies a scan, detailing what the image shows.)

"Immediately, I could see the abnormality and wondered if the patient had failed to tell us about a previous brain surgery in his younger years" or if the patient was born with a brain abnormality, Brown told Live Science. When doctors were told that neither of these scenarios applied to the patient, they were "left very curious as to the cause of these findings," Brown said. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

It turned out that the patient had a pocket of air inside his skull, called a pneumatocele, which was compressing his brain tissue. These air pockets are seen more commonly in patients who have facial trauma or infections, or who have had brain surgery, according to a report of the case, published Feb. 27 in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

Brown said he had never seen a case of brain pneumatocele tied to symptoms of falling, and he decided to publish this case to emphasize "the importance of thorough investigation of even the most common of symptoms," Brown said. "Because every now and then, there will be a rare [or] unknown causation of these that could be overlooked," he said.

When the patient first spoke with his doctors, he told them told that, in addition to his frequent falls, he felt weakness in his left arm and leg. But he was otherwise feeling well, and his initial physical exam was normal.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But when the man was sent for a CT scan, the doctors discovered the 3.5-inch (9 centimeters) air pocket in his right frontal lobe. An MRI scan also revealed an osteoma, or benign bone tumor, in a part of the skull that separates the brain from the nasal cavity, called the ethmoid bone.

The doctors determined that the osteoma wore away part of the ethmoid bone, which allowed air to be pushed, under pressure, into his brain, "creating a 'one-way valve' effect," the report said.

The MRI also revealed that the patient had experienced a small stroke related to the air pocket in his brain.

Doctors told the man that they could perform brain surgery to release the air from the cavity, which would allow his brain to resume its normal shape, as well as a separate surgery to remove the osteoma.

But as with any surgery, there would be some risks for the patient. For example, decompressing the brain area could have led to more problems, and the surgery might not have helped the patient's symptoms, Brown said.

Given the risks and potential benefits, the patient decided not to have the surgery. He was treated with a statin and anti-clotting medication to lower his risk of having another stroke, Brown said.

Twelve weeks after his hospital stay, the patient remained well and no longer felt weakness on his left side, the report said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.