Why Did These Medieval European Women Have Alien-Like Skulls?

Why were medieval women with egg-shaped skulls buried in Bavaria? A DNA analysis reveals their origins.

The discovery of mysterious, 1,500-year-old egg-shaped skulls in Bavarian graves has stumped scientists for more than half a century, but now some genetic sleuthing has helped them crack the case: The pointy skulls likely belonged to immigrant brides who traveled to Bavaria from afar to get married, a new study explains.

The finding indicates that these long-headed brides, who lived in the sixth century A.D., likely traveled great distances from southeastern Europe — an area encompassing the region around modern-day Romania, Bulgaria and Serbia — to what is now the southern part of modern Germany.

The long trek was certainly arduous, but the reward was great: Wedlock helped cement strategic alliances in medieval Europe, the researchers wrote in the study. [In Images: An Ancient Long-headed Woman Reconstructed]

Great migration

When the women with the alien-like skulls were alive, Europe was undergoing profound cultural change. The Roman Empire dissolved as the "barbarians" — the Germanic peoples that include the Goths, Alemanni, Gepids and Longobards — moved in and took over the region,the researchers wrote in the study. The foreign brides were buried in the cemeteries of one of these groups — the Baiuvarii — who lived in what is now modern-day Bavaria.

The discovery of the remains of these women perplexed archaeologists for decades. It's only possible to create pointy skulls, scientifically known as artificial cranial deformation (ACD), in early childhood, when the skull is soft and malleable. But archaeologists couldn't find any children with egg-shaped skulls in the cemetery. Moreover, the women were buried with local grave artifacts, rather than foreign ones, suggesting they had adapted to local culture.

Egg-shaped skulls are perceived as the ideal of beauty in some cultures, and may be a sign of status or nobility, the researchers noted.

These observations prompted scientists to wonder whether the women had migrated from elsewhere, perhaps from Eastern Europe, where cranial deformation was practiced as early as the second century A.D. in Romania; from Asia, the home of the nomadic Huns, a culture that also carried out cranial shaping; or from the local area, meaning that the Baiuvarii had adopted the head-changing practice themselves.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To solve the mystery, the researchers in the new study looked at the DNA of 36 adults — 14 who had egg-shaped skulls — from six Bavarian cemeteries. They also looked at the DNA of a local Roman soldier and two medieval women from Crimea and Serbia, where the mysterious women may have originated.

DNA deep dive

The pointy-skulled women were genetically very different from the other Baiuvarii, the researchers found.

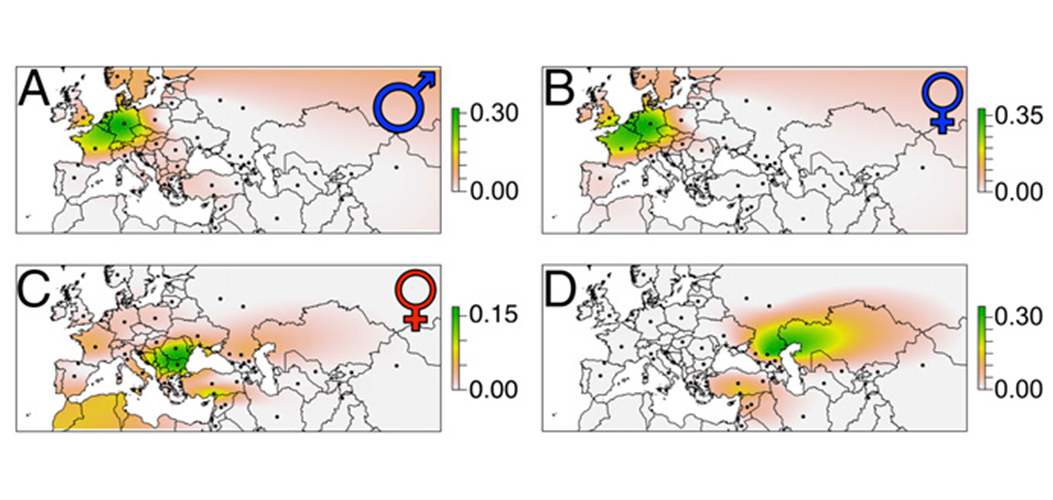

The men and women with normal skulls, with the exception of two individuals, had similar ancestry traced to northern and central Europe, the researchers said. In contrast, the women with deformed skulls largely hailed from southern and southeastern Europe. At least one of the women had East Asian ancestry.

Armed with this knowledge, it's fair to say that "adult females with deformed skulls found in Medieval Bavaria likely migrated from southeastern Europe, a region that not only contains the earliest known European burials of males and females with ACD but also the largest accumulation," the researchers wrote in the study.

Given the diversity of the women with alien-like skulls, it's possible that some came from southeastern European tribes, such as the Gepids, and Asian tribes, such as the Huns, the researchers noted. Or, perhaps all of the women came from southeastern Europe, which was already a melting pot of local and Asian tribes, they said. [In Images: Deformed Skulls and Stone Age Tombs from France]

The DNA analysis revealed that the pointy skulls weren't the foreign brides' only visible difference. The majority likely had brown eyes and blond or brown hair, while the normal-skulled people tended to have genes for blond hair and blue eyes.

The study was published online yesterday (March 12) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.