Oklahoma Turns to Nitrogen Gas for Executions

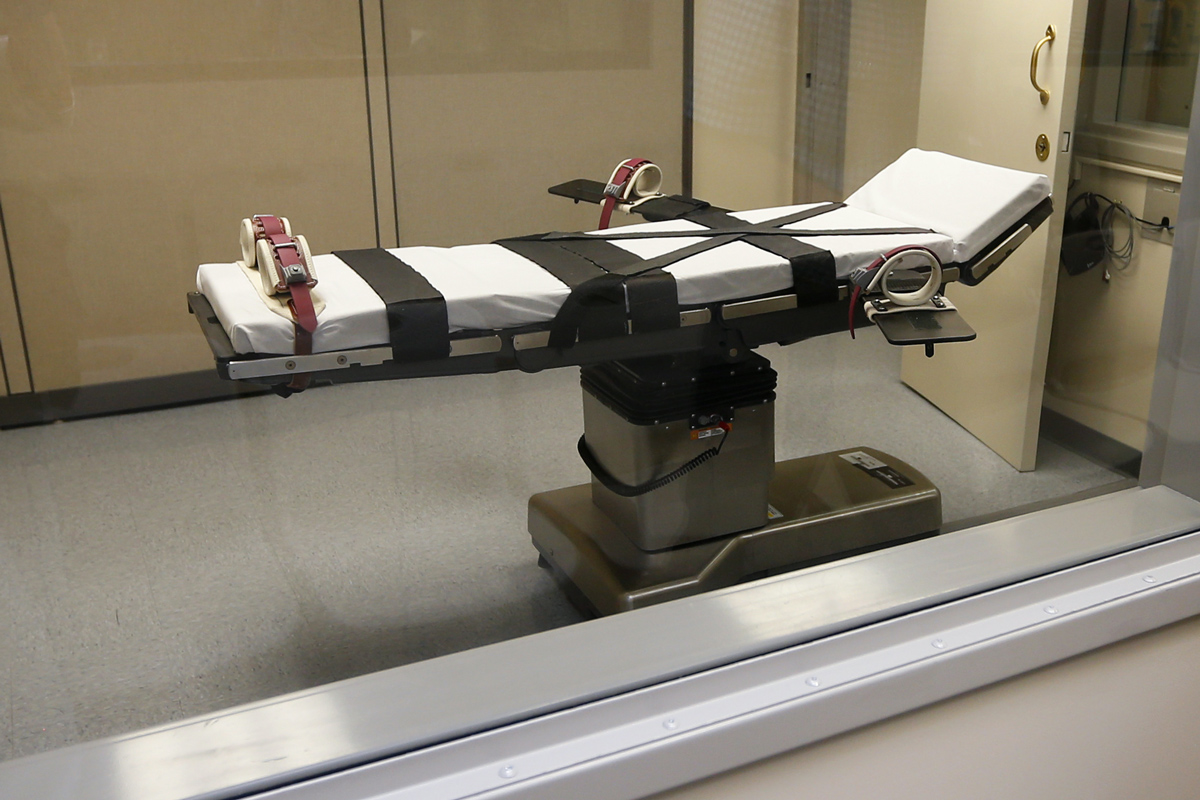

After an ongoing shortage of execution drugs that has left states scrambling, Oklahoma authorities have announced that it will use nitrogen gas to execute death-row inmates.

Death by nitrogen inhalation could potentially skirt the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of "cruel and unusual punishment," because inhaling this inert gas can render people unconscious within a breath or two. However, Oklahoma has yet to detail an execution protocol for using nitrogen gas, according to The Washington Post, and it's likely that any new execution method will be challenged in court.

"This method has never been used before and is experimental," Dale Baich, an attorney representing 20 of the state's death-row inmates, told the Post. "Oklahoma is once again asking us to trust it as officials 'learn-on-the-job,' through a new execution procedure and method." [Mistaken Identity? 10 Contested Death Penalty Cases]

The trouble with executions

Capital punishment has become increasingly challenging for states to carry out in recent years, as drugmakers have refused to sell their products to states for use in executions.

Because of this, prison officials have experimented with new drugs, and the results have sometimes been grisly. In Oklahoma in 2014, the execution of Clayton Lockett went terribly awry when prison officials used an untested three-drug injection to kill him. Lockett failed to slip into unconsciousness and spent more than 40 minutes writhing and mumbling before dying of a heart attack. In 2015, Oklahoma executed inmate Charles Warner with the wrong drug, using vials of potassium acetate either instead of or alongside the approved drug, potassium chloride. In his final moments, Warner complained that he felt like his body was on fire. Oklahoma has not carried out an execution since.

That same year, the state officially adopted nitrogen gas as a backup method of execution. Now, the state's attorney general and corrections director have announced that the gas will be the primary method of carrying out executions in Oklahoma due to the difficulty of getting lethal injection drugs.

How nitrogen kills

Nitrogen is an inert gas — meaning it doesn't chemically react with other gases — and it isn't toxic. But breathing pure nitrogen is deadly. That's because the gas displaces oxygen in the lungs. Unconsciousness can occur within one or two breaths, according to the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nitrogen inhalation doesn't cause the same panicked feeling that suffocation does, because the person continues to exhale carbon dioxide. Rising carbon dioxide in the blood is what triggers the respiratory system to breath. These levels are also responsible for the burning and pain that happens when you hold your breath for too long. Because the carbon dioxide levels in the blood never rise with nitrogen inhalation, these symptoms don't occur.

Hypoxia, or a lack of oxygen, kills pretty quickly. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, brain cells start dying within 5 minutes of oxygen deprivation starting. Death follows rapidly.

In the report favoring nitrogen as an execution method supplied to Oklahoma state legislators in 2015, the authors cited a 1961 study. That research found that human volunteers who hyperventilated, or rapidly breathed, pure nitrogen fell unconscious within 20 seconds. However, the World Society for the Protection of Animals lists nitrogen inhalation as "not acceptable" for animal euthanasia because loss of consciousness is not instantaneous, and dogs euthanized by nitrogen gas have been observed convulsing and yelping after falling unconscious.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.