Move Over, 'Tomb Raider': Here Are 11 Pioneering Women Archaeologists

Pioneering Women Archaeologists

Pistol-packing Lara Croft returned to theaters on March 16 in the film "Tomb Raider." Croft, played by Alicia Vikander, follows in the footsteps of her adventure-seeking father by traveling to distant lands and exploring remains of ancient civilizations, to piece together the events that led to his mysterious death.

In the context of prior "Tomb Raider" video games and comics — as well as the 2001 film about her exploits — Croft is often referred to as an archaeologist. But in the new movie's story she lacks a scientist's formal training in excavating sites and artifacts. Even the title of the film reflects a colonialist approach to archaeology that is considered highly unethical by archaeologists today, experts told Live Science.

However, there are plenty women who conducted truly groundbreaking archaeological work. Some of their pioneering contributions date back more than a century, and women today continue to forge new paths in the field by challenging how scientists investigate and interpret clues from the past.

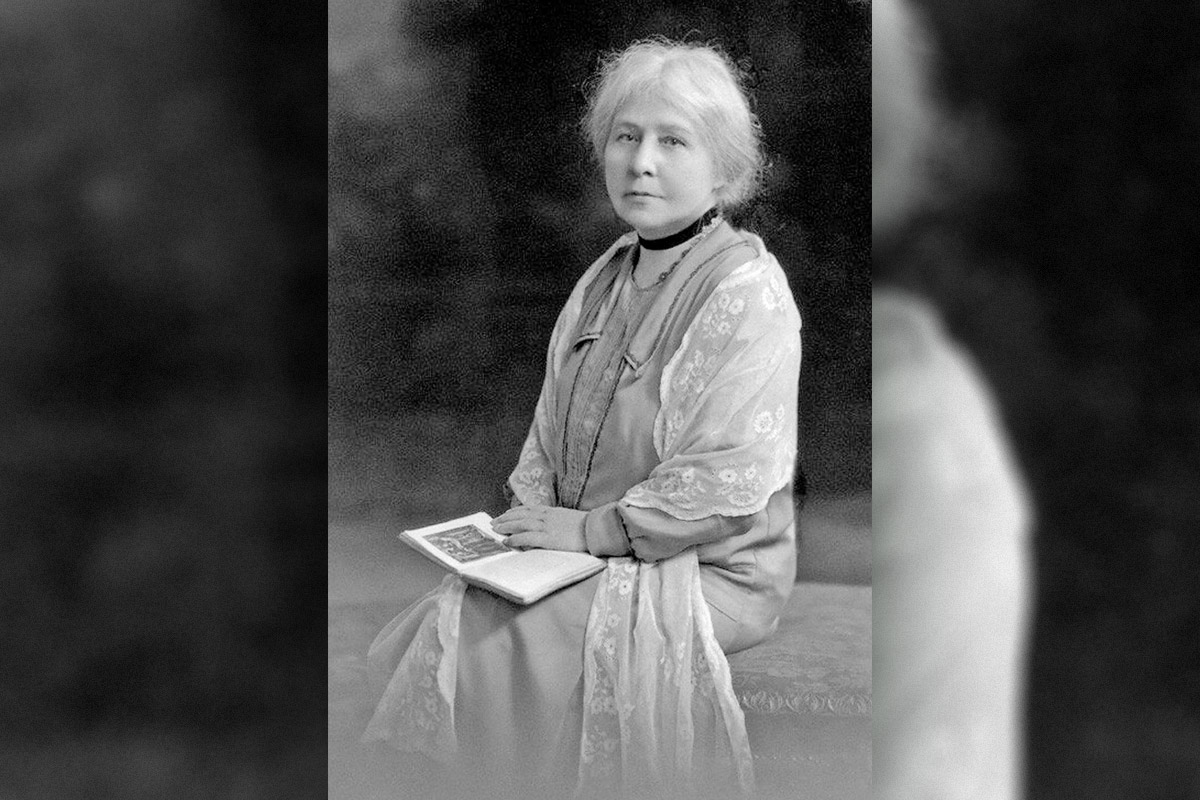

Margaret Murray (1863-1963)

British archaeologist and scholar Margaret Murray emerged in the late 19th century as a formidable figure in the developing specialty of Egyptology. In 1899 she became the first female lecturer in archaeology in the U.K., teaching at the University College London, and she led excavations in Malta, Menorca and Palestine, according to a study published in 2013 in the journal Archaeology International. Murray also collaborated with and mentored other women archaeologists, and she supported the civil actions of the suffragette movement in the U.K. — in a passage from her autobiography, "My First One Hundred Years" (William Kimber, 1963), Murray recounted that "young males, even though brilliantly clever, should not pit their wits against an organisation [sic] run by women."

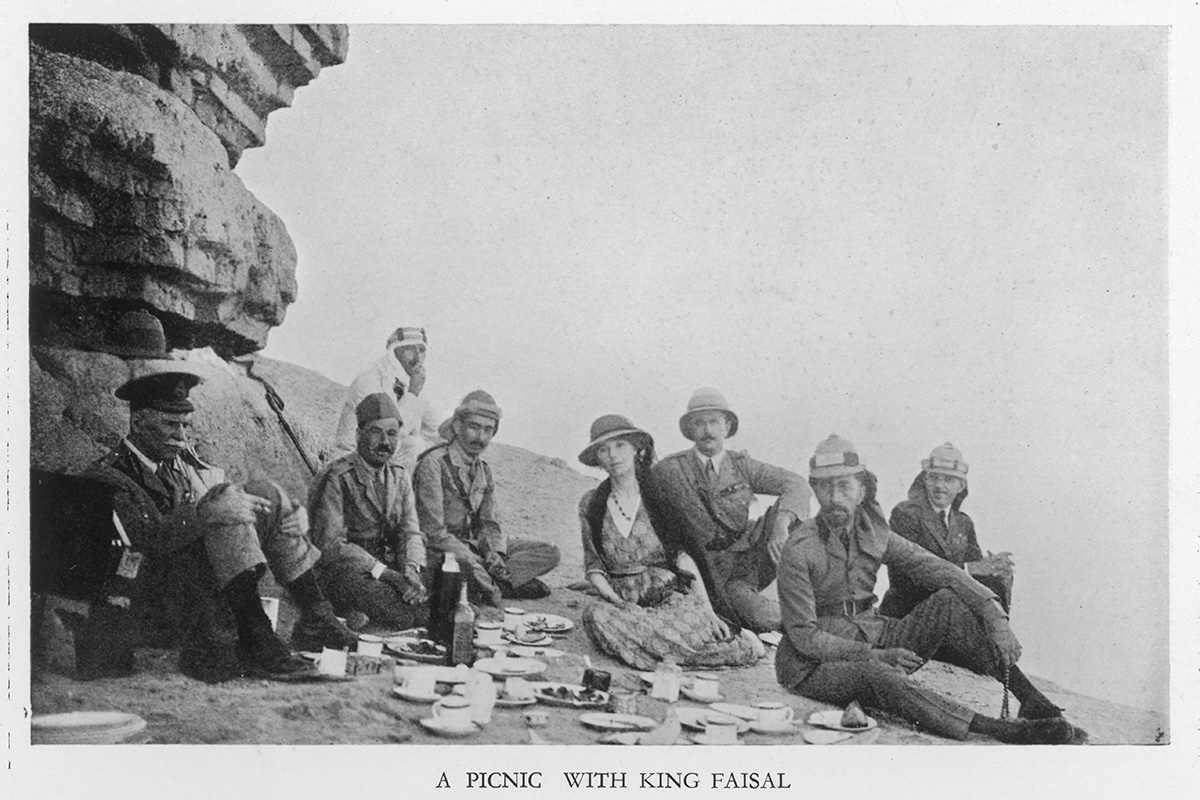

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926)

Born in the north of England, Gertrude Bell was the second woman to graduate from Oxford University in the U.K., a feat she followed up by traveling extensively throughout the Middle East visiting archaeological sites and exploring remote desert locations, according to Newcastle University's Gertrude Bell Archive. Along with her colleague T.E. Lawrence — better known as "Lawrence of Arabia" — she was considered to be one of the foremost European experts on Arab culture in the Western world, during the early 20th century. Bell led archaeological digs in Syria and Iraq, and wrote about her expeditions in highly-respected and popular accounts, according to an exhibit of her books, photos and papers presented at Yale University in 2011.

Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888-1985)

Wealth and race closely guarded the gateway to archaeology for many decades — and continue to play a part in the field's accessibility — and London-born Gertrude Caton Thompson's privilege enabled her to travel extensively with her family as a young woman, piquing her interest in archaeology with visits to historic sites in Rome and Egypt, according to a profile on Trowelblazers, an organization that offers resources for women and underrepresented groups in archaeological, geological, and palaeontological sciences. Caton-Thompson began her archaeological pursuits at age thirty-three, leading Neolithic and Paleolithic excavations in Egypt, Yemen and Zimbabwe, and her 1929 Zimbabwe dig was excavated entirely by women. Her methods, which included meticulous soil scrutiny and noting objects' positions relative to each other, revolutionized the way that sites were surveyed and studied.

Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968)

Paleolithic archaeologist Dorothy Garrod's work uncovered important findings about early human origins — including the first evidence of the Middle Stone Age, and the first evidence of dog domestication — and she was also the first to use aerial photographs for archaeological work, according to Michigan State University's Digital Encyclopedia of Archaeologists. Garrod's excavations encompassed 23 sites in seven countries, including Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq, Lebanon, Bulgaria, France, Gibraltar and Great Britain, and she faced the intense physical challenges of field work with humor, writing about an excavation in 1934, "There was considerable consternation as there had been predictions of a cloudburst, an earthquake and the end of the world," according to a diary excerpt published online by the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K.

Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978)

Excavator of the ancient city of Jericho, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon chose a career in archaeology after working on Gertrude Caton-Thompson's 1929 Zimbabwe excavation, according to a review of the biography "Dame Kathleen Kenyon: Digging Up the Holy Land" (Routledge, 2008) by Miriam Davis; the review was published in 2008 in the journal Archaeology. Kenyon used a then-novel technique called stratigraphic analysis — peering downward through layers of soil and rock — to better understand how materials accumulate on a dig site, and she was awarded the honor Dame of the British Empire in 1973 for her archaeological and academic achievements, according to Michigan State University's Digital Encyclopedia of Archaeologists.

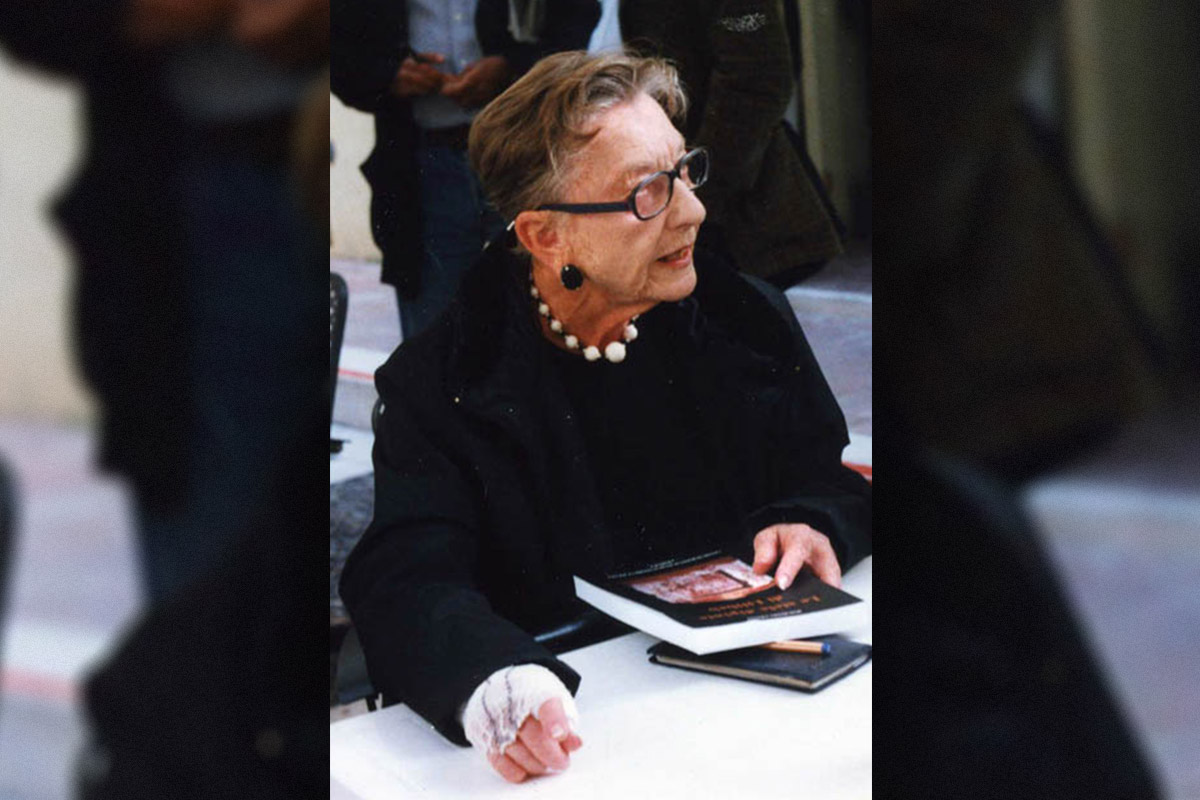

Honor Frost (1917-2010)

Honor Frost was the first to usher in an era of underwater archaeology, using her skills as a diver to pioneer the excavation and reconstruction of submerged shipwrecks, according to an obituary published by the Guardian in 2010. Frost got her start in archaeology working under Kathleen Kenyon in Jericho in 1957, and she later moved on to explore sites in Lebanon, working with Beirut's Institut Français d'Archéologie. Beginning in the 1960s, Frost incorporated archaeology with her love of deep-sea diving, leading dives and organizing excavations of sites and shipwrecks in the Mediterranean that included the discovery of the lost palace of Alexander and Ptolemy in the Port of Alexandria, the Honor Frost Foundation says.

Gudrun Corvinus (1932-2006)

Paleontologist, geologist and archaeologist Gudrun Corvinus researched and excavated sites across Asia and Africa, and her discoveries informed the understanding of vertebrate paleontology and Paleolithic archaeology, according to an editorial published online in 2008 in the journal Quaternary International. In the 1970s, Corvinus was part of the team in Ethiopia that discovered "Lucy," the partial skeleton of a human ancestor known as Australopithecus afarensis that lived 3.2 million years ago. She later discovered Paleolithic sites in Ethiopia that were determined to be "among the oldest archaeological evidence in the world," and unearthed numerous Paleolithic sites in India, Nepal and Tibet, according to the editorial.

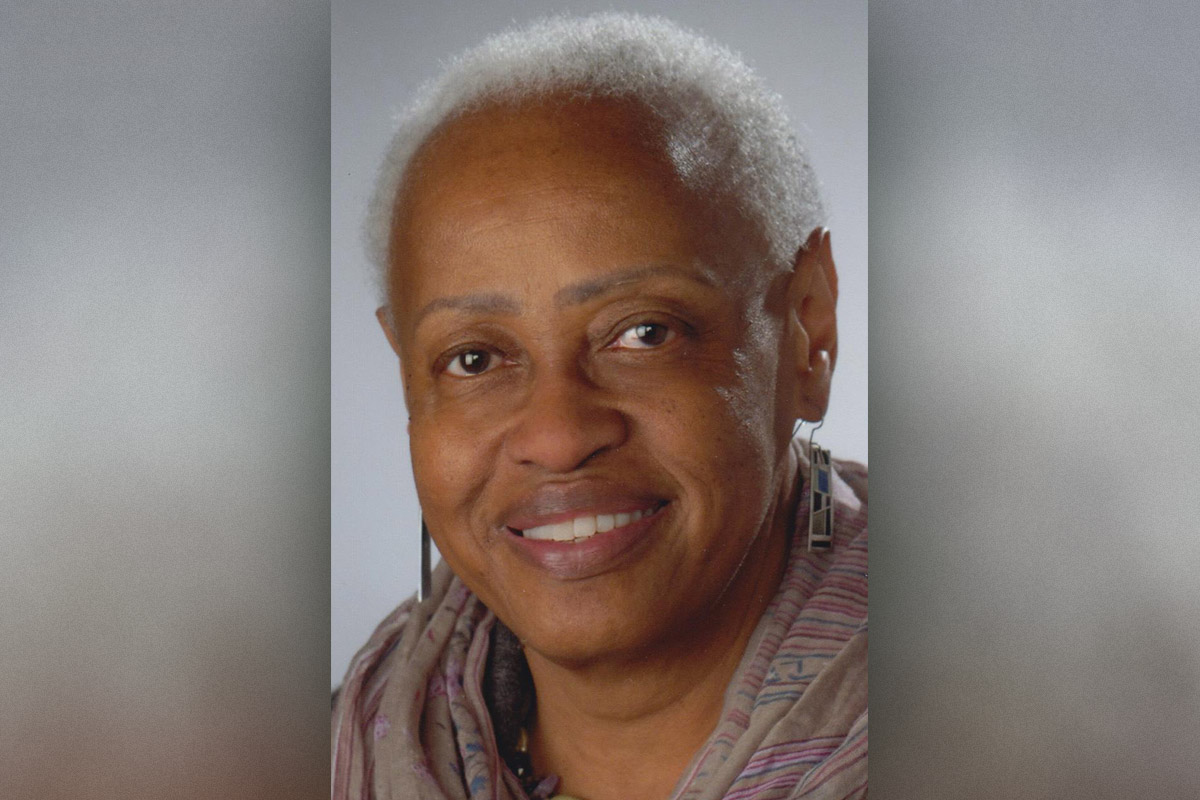

Theresa Singleton

Writer and archaeologist Theresa Singleton was born in South Carolina and studied archaeology at Oxford University in the U.K. and at Florida State University, where she was a pioneer of historical archaeology in North America, according to an article published in 2014 in the journal Historical Archaeology. Her work uncovered important findings representing the African Diaspora, particularly African-American history and culture under slavery, and life in communities of African-Americans descended from former slaves. In 2014 she became the first African-American recipient of the Society of Historical Archaeology's J.C. Harrington Award — the organization's highest honor — for her contributions to the field, Syracuse University representatives announced in a statement released that year.

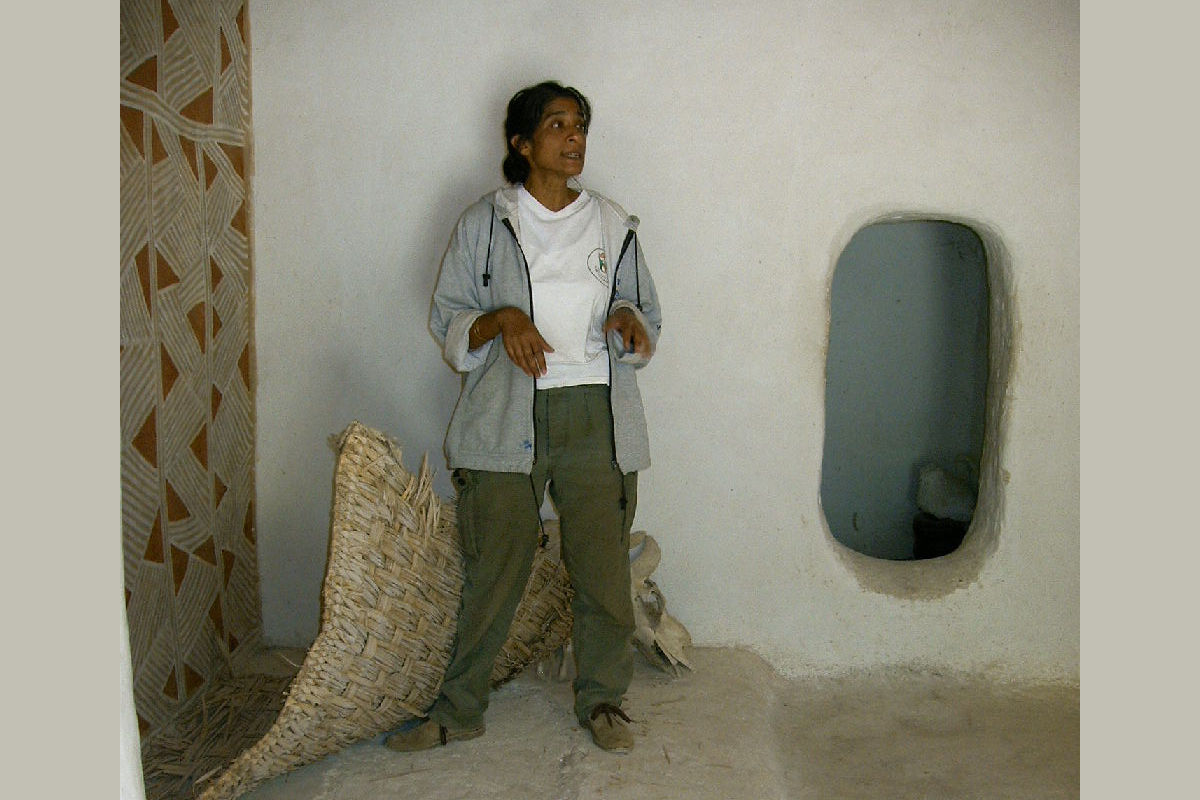

Shahina Farid

Born in London to parents who emigrated from Pakistan, Shahina Farid began volunteering on local dig sites when she was still in her teens, and studied archaeology at the University of Liverpool, according to a profile on the Trowelblazers website. Farid has contributed to archaeology projects in Turkey, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, as well as in London, and has published more than 40 scientific articles about her work. For two decades, she also served as field director for the Çatalhöyük project — excavation of a Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlement in southern Anatolia dating from about 7,500 B.C. to 5,700 B.C. — where she managed an international team of over 200 scientists, volunteers and students.

Alexandra Jones

Alexandra Jones is a modern ambassador for archaeology. She uses her background in teaching and in historical archaeology to perform outreach on platforms such as the PBS archaeology show "Time Team America," and with her own organization, Archaeology in the Community, which she founded in 2006, according to a Trowelblazers profile. Jones studied biology at Howard University in Washington, D.C., intending to pursue a career in medicine. But she opted for degrees in history and anthropology, and then later received a degree in historical archaeology from the University of Berkeley in California. "I am passionate about empowering future generations through the knowledge and perspectives only archaeology can provide," Jones told Howard University's Howard Magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.