Trash in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Has Quadrupled, Maybe Even 16-upled

This story was updated March 22 at 2:44 p.m. EDT.

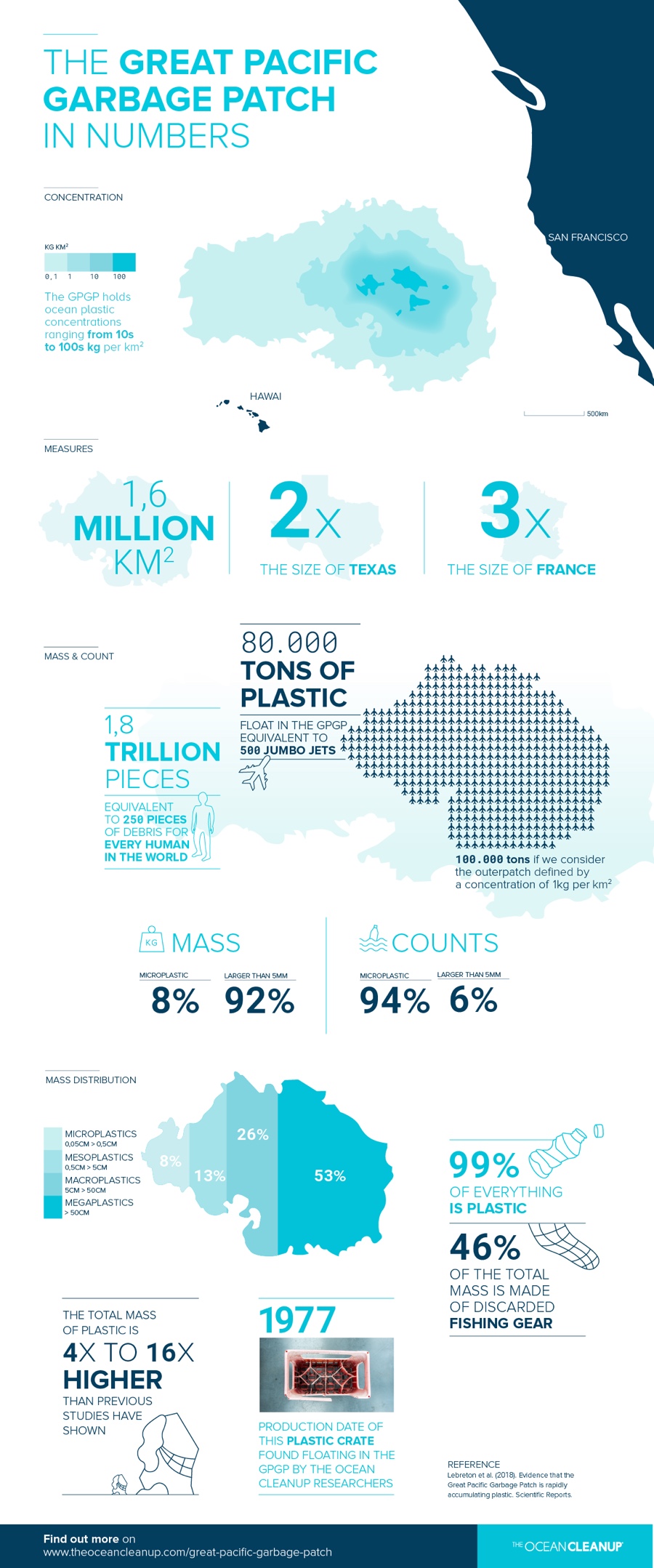

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is getting denser. The enormous plastic soup floating in the vast North Pacific spans more than 617,000 square miles (1.6 million square kilometers), and its density is now between four and 16 times greater than previous estimates, scientists have found.

Researchers made the discovery by looking at the accumulation of plastic trash in the Pacific between California and Hawaii. They found that the patch has more than 87,000 tons (79,000 metric tons) of plastic in it. That equates to 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, or roughly 250 pieces for every person on the planet, the researchers said.

Moreover, the concentration of tiny pieces of plastic, known as microplastics, has exponentially increased since the 1970s, like a person adding more pulp to a glass of orange juice. In the 1970s, the patch housed 2.28 lbs. of plastic per square mile (0.4 kilograms per square kilometer), but by 2015, that number had grown to 7.02 lbs. of plastic per square mile (1.23 kg per square km), the researchers found. [In Images: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch]

The researchers also looked at the size of the plastics in the water. While debris larger than 2 inches (5 centimeters) across accounted for more than 75 percent of the total weight of the plastics, there were far more microplastics, which represented the majority of the 1.8 trillion pieces inside the patch, said Laurent Lebreton, the lead researcher of the Ocean Cleanup Foundation and the lead author of the study. The foundation aims to develop technologies that can extract the plastic from the garbage patch.

"Plastic pollution in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is more severe than expected," Lebreton told Live Science in an email, adding that the study results "are alarming and support the urgency of the situation and the necessity to take action rapidly."

By air and sea

The Ocean Cleanup was founded by Dutch inventor Boyan Slat in 2013, when he was just 18 years old. The new study was paid for, in part, by a crowdfunding campaign in 2014 that raised more than $2 million, according to Slat, who is the study's second author.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to thanking their donors, the researchers also tipped their hats to Taylor Swift, a fisherman who helped construct the mega nets used during the first expedition and deployed onboard the RV Ocean Starr. Funnily enough, Swift owns the Taylor Swift gmail address, and "regularly receives love (and hate) letters in his mailbox," for the singer, Lebreton said.

Once the foundation had the money and equipment, its scientists conducted reconnaissance missions into the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between 2015 and 2016 to get a more accurate picture of the plastic out there, Lebreton said. These missions included 652 net tows carried out by 18 vessels, as well as a reconnaissance trip on a C-130 Hercules aircraft

After collecting water samples, "we also carried out laboratory experiments to quantify, characterize and understand physical properties of buoyant plastic collected at sea," Lebreton said. "Finally, we developed a numerical model to supplement our field data, allowing us to provide more insights on the patch's dynamics and composition." [Infographic: Take a Tour from the Tallest Mountain to the Deepest Ocean Trench]

The results showed that plastics made up 99.9 percent of the debris in the patch. Fishing nets accounted for at least 46 percent of the plastic, the researchers found. Smaller items had broken into fragments, but researchers still managed to identify quite a few objects, including containers, bottles, lids, packaging straps and ropes. Fifty items even had discernable dates, including one from 1977, seven from the 1980s, 17 from the 1990s, 24 from the 2000s and one from 2010.

"Debris were predominantly made of hard, thick polyethylene and polypropylene fragments and derelict fishing gear," Lebreton said.

Whose plastic is it?

The plastic in the patch comes from both land and marine sources, as well as from the 2011 Tohoku tsunami that hit Japan.

"On land, implementing better waste management practices and diverting consumption away from single-use plastics [such as water bottles] may help stem the tide of plastic at sea in the coming years," Lebreton said. "In the ocean, developing better technologies for the fishing and aquaculture industries to retrieve lost gear may also help mitigate the problem."

These plastics can harm marine life, which can get tangled up in the debris. Animals can even chow down on small bits of trash, which can lead to starvation because the plastic takes up room in their stomachs but offers no nutritional value. The plastics can also contaminate the animals with persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which were found in 84 percent of the ocean plastic collected by the trawls, Lebreton said.

Outside take

The fact that the garbage patch is growing is also supported by research coming out soon by Capt. Charles Moore, who discovered the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 1997.

He noted that the large disparity in the density of the patch now compared with previous estimates — that is, four to 16 times higher than previously thought — is due to different methods researchers have used to calculate the patch's innards in the past. Some researchers have looked at larger pieces of plastic, which led them to underestimate the density of the patch, he said. In contrast, others measured as many plastic bits as possible, especially the microplastic pieces, which gave a more realistic view of the patch's magnitude, said Moore, who was not involved with the new study.

Despite these differences, the key point is that research shows the patch is getting denser as time marches on. "We are destroying [the oceans] with our trash," Moore told Live Science.

The study was published online today (March 22) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to clarify that the garbage patch is getting denser, not larger in size.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.