Oldest Human Footprints in North America Discovered: Here's What They Reveal

About 13,000 years ago, two shoeless adults and a child squished their bare feet through wet clay near the water's edge, leaving footprints that still exist today.

The footprints, recently unearthed by anthropologists on an island in British Columbia, Canada, are the oldest known human track marks in North America, according to a new study, and provide more evidence that humans were thriving on the Pacific Coast of Canada at the end of the last ice age, said study lead researcher Duncan McLaren, an anthropologist at the Hakai Institute and the University of Victoria, in Canada.

The footprints — 29 in all — were so well preserved that McLarenand his colleagues could assign modern-day U.S. shoe sizes to the prehistoric individuals: a junior size 8; a junior size 1 (or a woman's size 3); and a woman's size 8 or a man's size 7. [In Photos: Stone Age Human Footprints Discovered]

The researchers made the remarkable discovery on Calvert Island, located off the western coast of British Columbia, about 62 miles (100 kilometers) north of Vancouver Island.

At the end of the last ice age (about 11,700 years ago), the North American Cordilleran Ice Sheet ended along the Pacific coastline, leaving "refugia," or iceless areas where plants and animals could survive. Calvert Island fell right into one of these refugia, prompting modern-day researchers to dig there, looking for artifacts. However, excavations in refugia aren't always easy, as today much of the region is covered with dense temperate rainforest, the researchers wrote in the study.

Moreover, the geography there was different at the end of the last ice age because more of Earth's water was frozen in huge glaciers. This explains why sea levels were as much as 9.8 feet (3 meters) lower about 14,000 to 10,000 years ago on Calvert Island than they are today, McLaren said.

The first footprint

"We were testing this shoreline, below the beach in the intertidal zone, when the first footprint was discovered," McLaren told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This was in 2014, when the team — which included members of the Heiltsuk First Nation and the Wuikinuxv First Nation — unearthed a single human footprint about 24 inches (60 centimeters) below the beach's surface on Calvert Island. Two pieces of ancient wood found by the footprint dated to between 13,300 and 13,000 years ago, according to radiocarbon analyses, the researchers found.

Encouraged, the researchers returned to the island during the 2015 and 2016 field seasons, eventually uncovering 28 more human footprints from the same period.

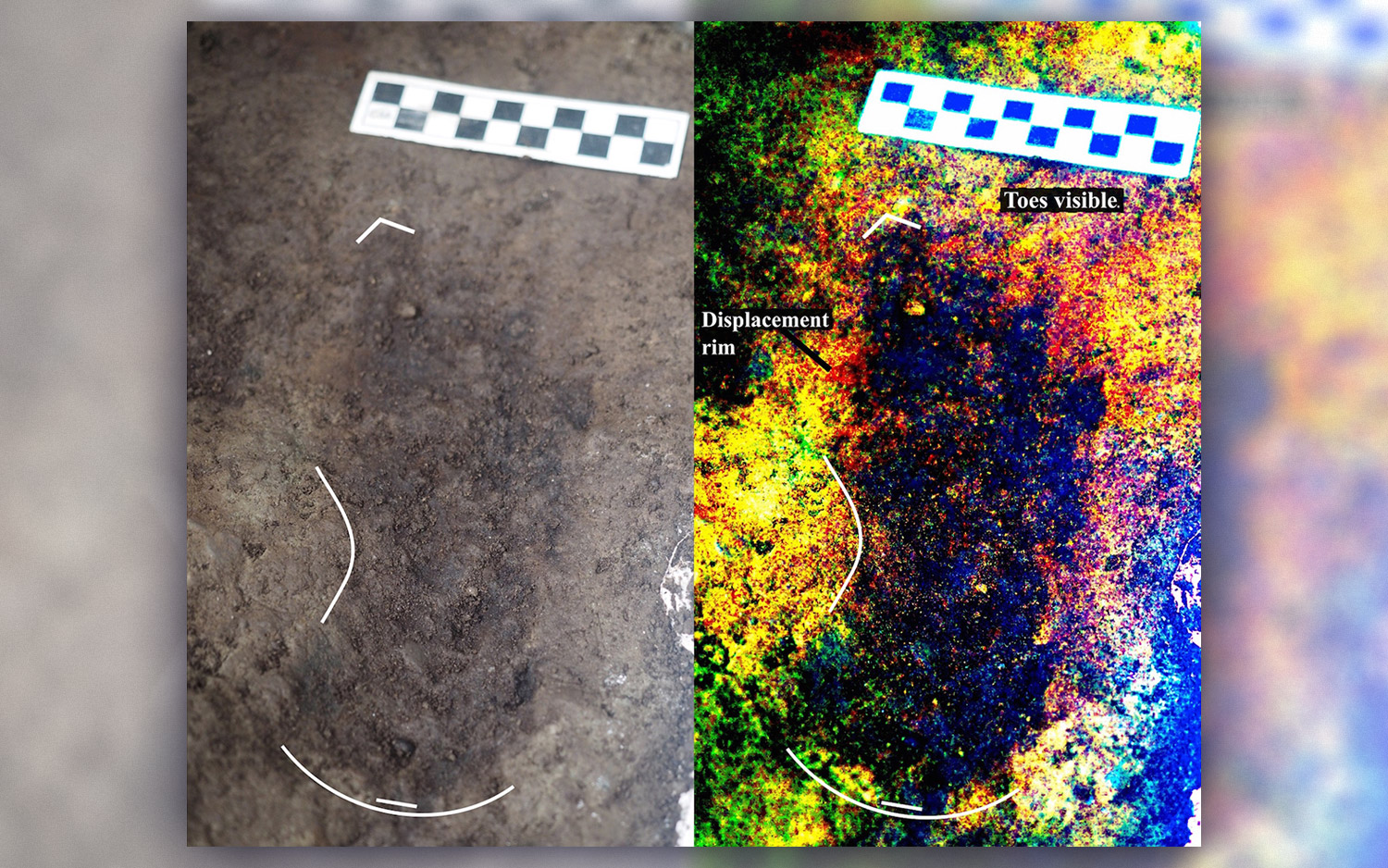

Normally, footprints last only a moment. But in this case, "they were impressed into a wet clay that hardened and then was filled by sand, likely washed in from the beach below," McLaren said.

Not a bear

The 29 footprints have clear arch, toe and heel marks, so the scientists are "certain that they were left by human feet," they wrote in the study. But given that British Columbia is home to bears, and the hind paw of black and grizzly bears can leave footprints similar to a human's, they had to ask the question: Are these bear tracks?

A thorough analysis reveals that "no," these are likely not bear tracks, the researchers said. [Photos: These Animals Used to Be Giants]

"The tracks excavated on Calvert Island have a clearly defined arch, lack characteristic claw marks, are not triangular in overall shape … lack a long third [toe] and they are overall narrower than bear tracks," the researchers wrote in the study. In addition, they couldn't find any bear pawprints at the site.

In fact, "overall, nonhuman tracks of any kind are lacking from the area that was excavated," the researchers wrote in the study.

Prehistoric boating

Calvert Island was still an island during the last ice age, indicating that prehistoric people used boats to reach it, McLaren said. It's possible the footprints were left "by a group of people disembarking from watercraft and moving toward a drier central activity area to the north or northwest," the researchers wrote in the study.

The oldest documented site of prehistoric people along the west coast of North America is Manis Mastodon, on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state. At Manis Mastodon, researchers found a bone point lodged into a mastodon rib that's dated to about 13,800 years ago. The oldest known human-inhabited site in Canada is younger — a group of artifacts, including a stone weapon, found at Charlie Lake Cave in British Columbia dates to about 12,500 years ago, the researchers said.

The new finding is "encouraging for future researchers who might employ similar methods to identify archaeological sites along the Pacific Coast," said Kevin Hatala, an assistant professor of biology at Chatham University, in Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

"Ultimately, the data seem to show indisputable evidence for human presence along the Pacific Coast of Canada," Hatala told Live Science. "This is important because archaeological sites from this time and place have been quite rare."

The study was published online today (March 28) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.