Lise Meitner: Life, Findings and Legacy

Lise Meitner was a pioneering physicist who studied radioactivity and nuclear physics. She was part of a team that discovered nuclear fission — a term she coined — but she was overlooked in 1945 when her colleague Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. She has been called the "mother of the atomic bomb," even though she did not directly have anything to do with its development. Element No. 109, meitnerium, was named in her honor.

Life and findings

Lise Meitner was born on November 7, 1878, in Vienna, the third child in eight in her Jewish family.

Because of Austrian restrictions on female education, Meitner wasn't allowed to attend college; however, her family could afford private education, which she completed in 1901. She went on to graduate school at the University of Vienna. Inspired by her teacher, physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, she studied physics and focused her research on radioactivity. She became the second woman to receive a doctorate degree at the university in 1905.

Shortly thereafter, physicist Max Planck allowed her to sit in on his lectures — a rare gesture for him; before then, he had rejected any women wanting to attend his lectures. Meitner later became Planck's assistant. She also worked with Hahn, and together they discovered several isotopes.

In 1923, Meitner discovered the radiationless transition. Unfortunately, she didn't receive much credit for the finding. It is called the Auger effect because Pierre Victor Auger, a French scientist, discovered it two years later.

Meitner and Hahn were research partners for around 30 years. During their research, they were one of the first to isolate the isotope protactinium-231, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. The pair also studied nuclear isomerism and beta decay and each of them headed a section in Berlin's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. In the 1930s, Fritz Strassmann joined the team, and the trio investigated the products of neutron bombardment of uranium.

In 1938, after Germany annexed Austria, Vienna-born Meitner fled Nazi Germany and moved to Sweden, where it was safer for the Jewish people like herself, even though she was a practicing Protestant. She found herself at the Manne Siegbahn's institute in Stockholm, but she never seemed welcomed. Ruth Lewin Sime later wrote in her book, "Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics," "Neither asked to join Siegbahn's group nor given the resources to form her own, she had laboratory space but no collaborators, equipment, or technical support, not even her own set of keys to the workshops and laboratories." Meitner was considered separate "from the institute's own personnel" instead of the brilliant scientist she was. It is believed that Siegbahn's prejudice against women in science played a large part in her treatment.

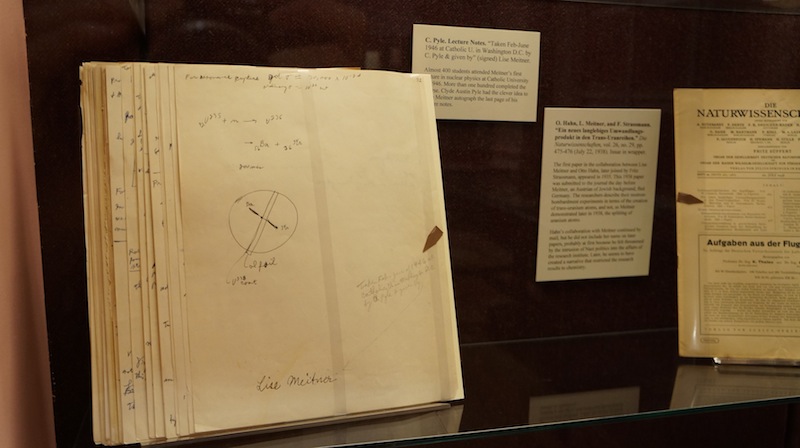

On November 13, 1938, Hahn met secretly with Meitner in Copenhagen, according to Sime. She suggested that Hahn and Strassmann perform further tests on a uranium product they suspected was radium. The substance was actually barium, and they published their results in the journal Naturwissenschaften in January 6, 1939.

At the same time, Meitner joined forces with her nephew Otto Frisch, and in January 1939, they came up with the term "fission." Fission is when an atom separates and creates energy. They also explained the process in a paper that was published in the journal Nature on February 11, 1939. Frisch would later write about his aunt, "Boltzmann gave her the vision of physics as a battle for ultimate truth, a vision she never lost."

"It was Lise Meitner who explained these experiments as splitting atoms. When this paper appeared, all the leading physicists at the time immediately realized, here was a source of great destructive energy," said Ronald K. Smeltzer, a curator of the Grolier exhibition, a look at extraordinary women in science.

Actually, the report alarmed those leading physicists. Albert Einstein was persuaded to write a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning him of the destructive potential. This effort eventually led to the establishment of the Manhattan Project. Meitner turned down an offer to work on the development of the atomic bomb, according to Sime. Nevertheless, after World War II she was dubbed "the mother of the atomic bomb," even though she had nothing directly to do with the bomb.

Awards

Though her research was revolutionary, Meitner was given very little acclaim. In 1945, Hahn received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission. Meitner was completely overlooked in the award. In 1966, all of the collaborators, Hahn, Strassmann and Meitner, were awarded the U.S. Fermi Prize for their work. Meitner retired to England in 1960 and died October 27, 1968, in Cambridge, England.

Impact

Today, many consider Lise Meitner the "most significant woman scientist of the 20th Century." Meitner is known for her important findings in nuclear physics, which compare with another famous female scientist, Irène Curie.

In 1992, the heaviest known element in the universe, element 109, was named meitnerium (Mt) in her honor.

Additional Resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.