Here's How to Track the Chinese Space Station's Uncontrolled Plunge to Earth

This story was updated March 30 at 5:24 p.m. EDT.

It's time to grab the popcorn: The Chinese space station Tiangong-1 is plummeting back to Earth this weekend, and anyone with an internet connection can track the fiery demise live online.

Tiangong-1 is expected to re-enter Earth's atmosphere sometime between late Saturday (March 31) and late Sunday (April 1), the European Space Agency reported, according to Live Science.

The show will likely be spectacular, and people can track its re-entry by pulling data from two websites. [In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth]

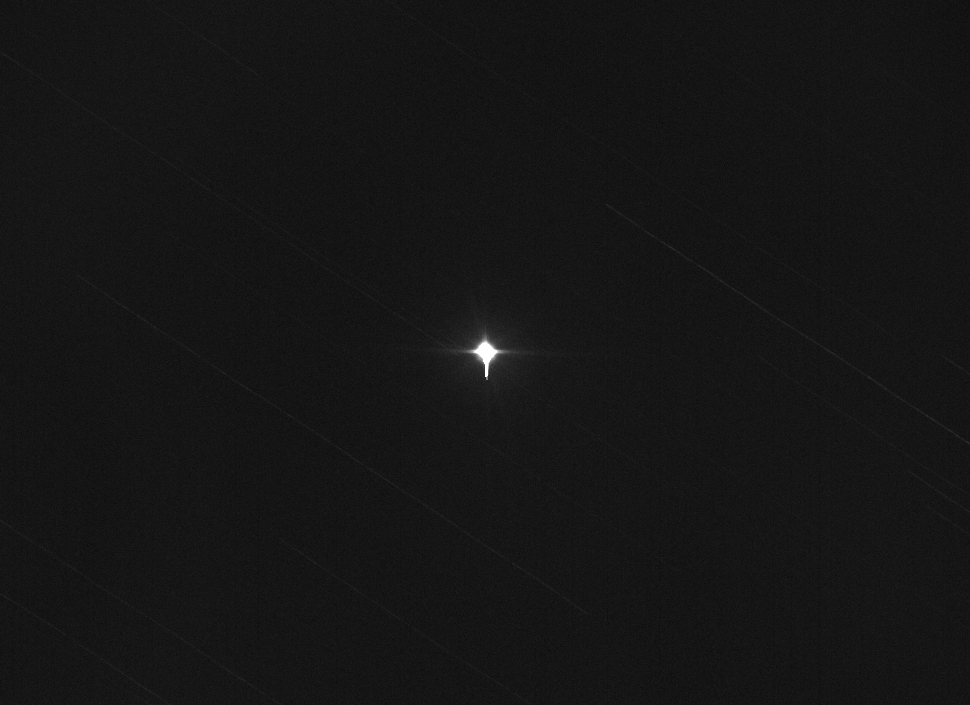

Online enthusiasts already glimpsed a live feed of the space station from the comfort of their homes, thanks to the Virtual Telescope Project in Italy and the Tenagra Observatory in Arizona. The team posted the video here, and even captured this dazzling photo of Tiangong-1 on March 28.

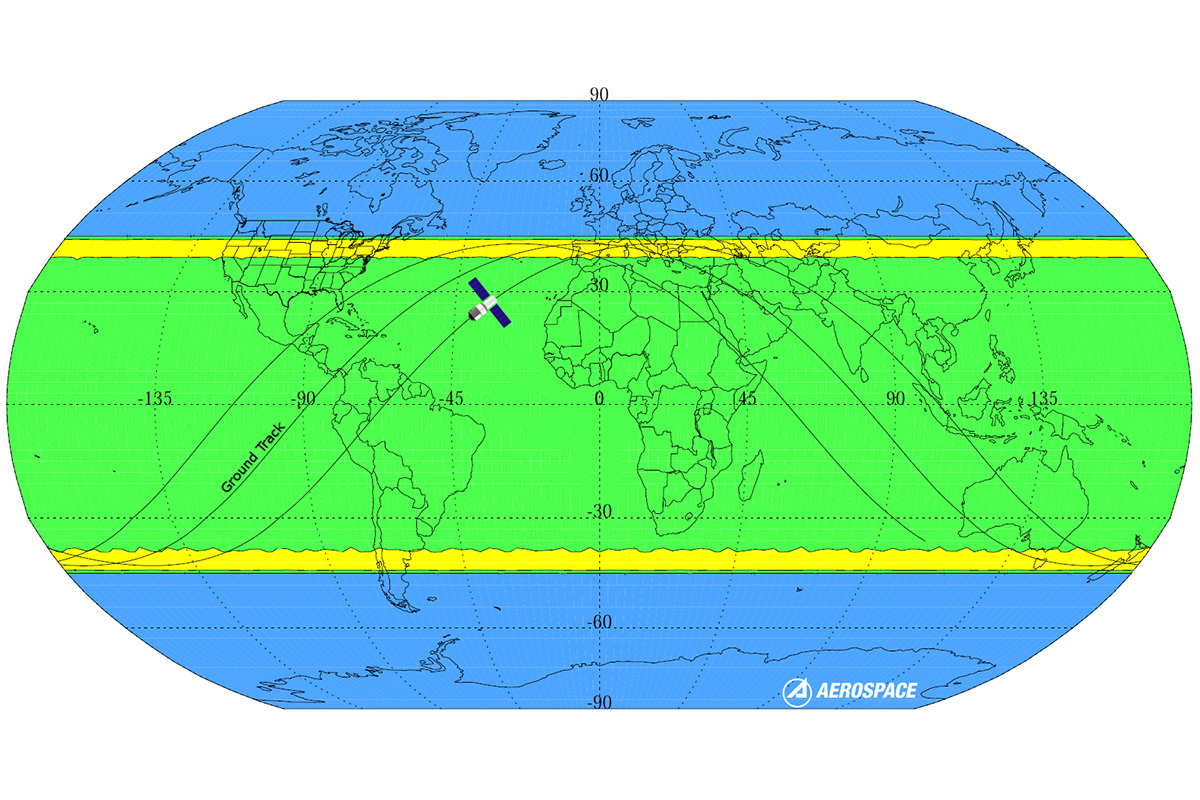

Star gazers hoping to see the Chinese space station this weekend can check Aerospace Corp., a nonprofit research organization in California that advises on military, civil and commercial space operations. By clicking on the site's "Where is Tiangong-1 now?" dashboard, people can see a digital view of Tiangong-1, as well as it's time to re-entry.

In addition, people can go to n2yo.com, a site that provides live tracking of satellites. Its useful maps will also help people zero in on Tiangong-1's location. Just be ready to have the sites loaded when Tiangong-1 is expected to make its uncontrolled descent toward the planet at about 3:15 p.m. UTC (11:15 a.m. EDT) on Sunday, give or take 11 hours, according to Aerospace Corp.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

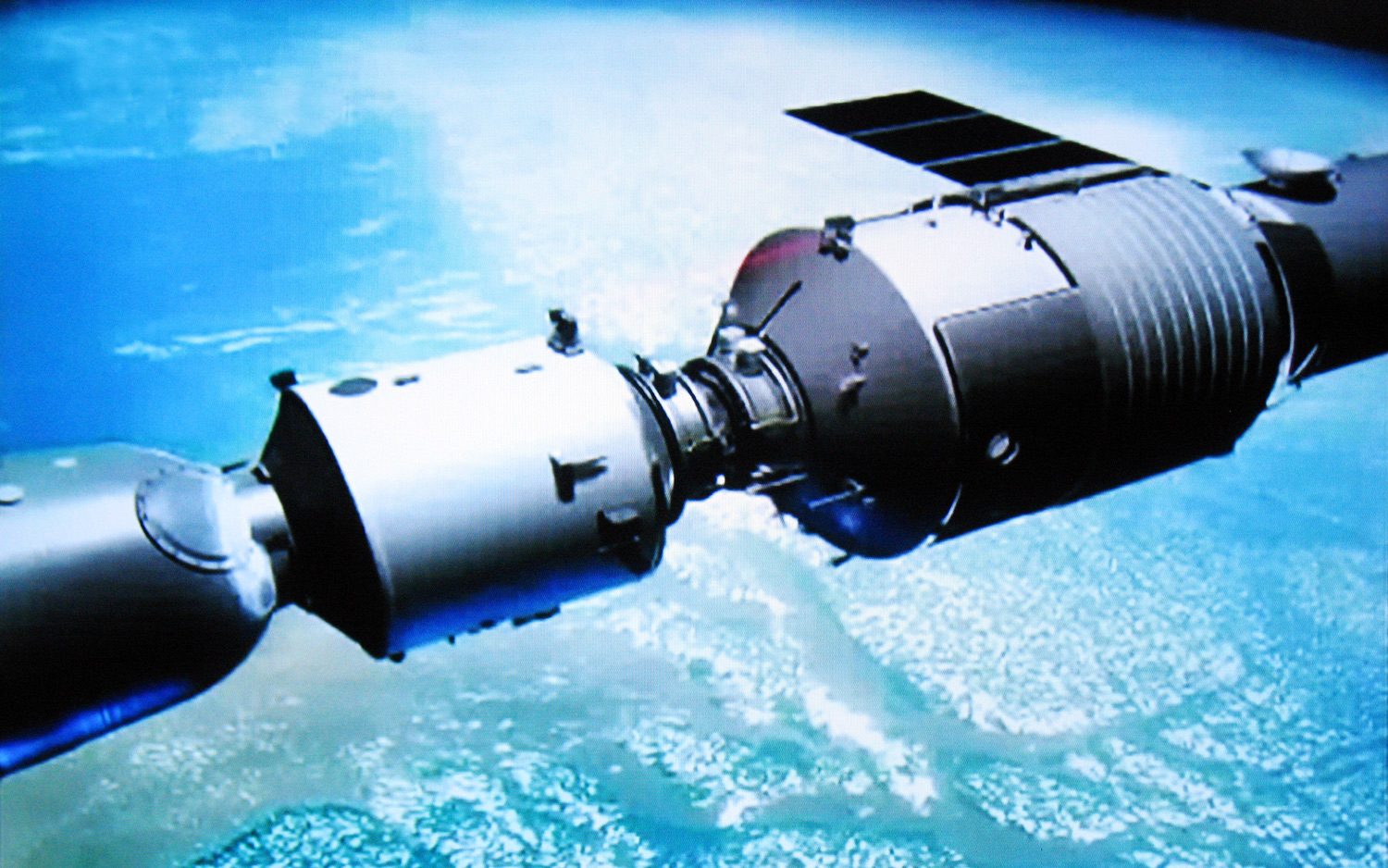

Tiangong-1 blasted into outer space in September 2011 and is China's first space station. It measures about 34 feet (10 meters) long and weighs 18,740 lbs. (8,500 kilograms), Aerospace Corp. reported. After China sent one uncrewed and two crewed missions to Tiangong-1, the country's space agency announced in March 2016 that the spaceship had stopped sending data to Earth.

Tiangong-1 lacks a heat shield, so it will begin to burn up from the incredible friction it encounters as it re-enters the atmosphere. It will also rapidly decelerate and break apart as it tumbles into the thick atmosphere, Live Science previously reported.

However, a few bits may make it through the atmosphere and reach the ground or water. But don't be alarmed; only certain parts of Earth are at risk, and the risk of getting hit in these parts is about 1 in 292 trillion, or about 1 million times smaller than the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot, Aerospace Corp. said.

However, if you're lucky enough to come across some Tiangong-1 debris, here's some advice: Don't touch it. The space station parts could be covered in hazardous materials, such as noxious fuel, and they could have dangerously sharp edges, Robert Z. Pearlman, a space historian and editor of collectSPACE.com, previously told Live Science.

Moreover, it's not finders keepers. China owns the space station unless it says otherwise, no matter where the debris lands, Pearlman noted.

In other words, enjoy tracking Tiangong-1 crash into Earth this weekend, but don't expect to find anything. In the off-chance you do, steer clear of it.

Editor's Note: This article has been to clarify that the watch-live event has ended, but that people can still track Tiangong-1 online.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.