Antarctica's Underwater Ice Is Retreating 5 Times Faster Than It Should Be

When you imagine an Antarctic glacier melting, you probably envision great walls of ice avalanching into the ocean in jagged, splashing chunks. This is certainly happening — but it's only half the story.

At the same time, hundreds of feet inland and deep underwater where even remote-controlled submersibles cannot venture, the warming ocean is also chipping away huge swaths of Antarctica's frosty underbelly. According to a new study published yesterday (April 2) in the journal Nature Geoscience, ice is receding deep below eight of Antarctica's largest glaciers at an alarming rate — roughly five times faster than it should be. If this marine ice recession continues, it could lead to a total collapse of the world's largest ice sheet, the study found. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

"Our study provides clear evidence that retreat is happening across the ice sheet due to ocean melting at its base," lead study author Hannes Konrad, a climate researcher at the University of Leeds in England, said in a statement. "This retreat has had a huge impact on inland glaciers, because releasing them from the sea bed removes friction, causing them to speed up and contribute to global sea level rise."

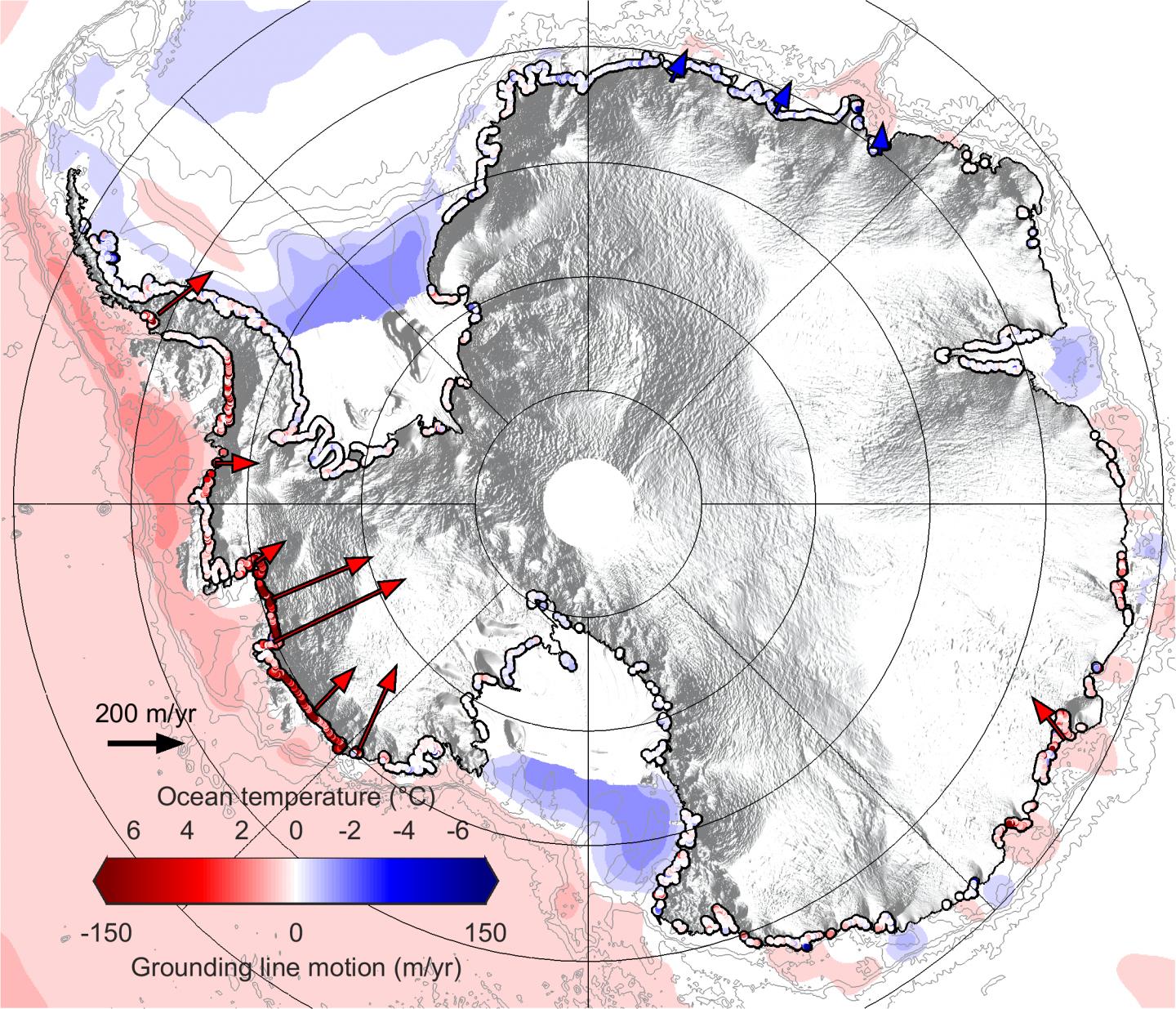

In the new study, Hannes and his colleagues at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) at the University of Leeds used a combination of satellite imagery and buoyancy equations to map out the invisible retreat of underwater ice across roughly 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) of Antarctica's coastlines — roughly one-third of the continent's total perimeter.

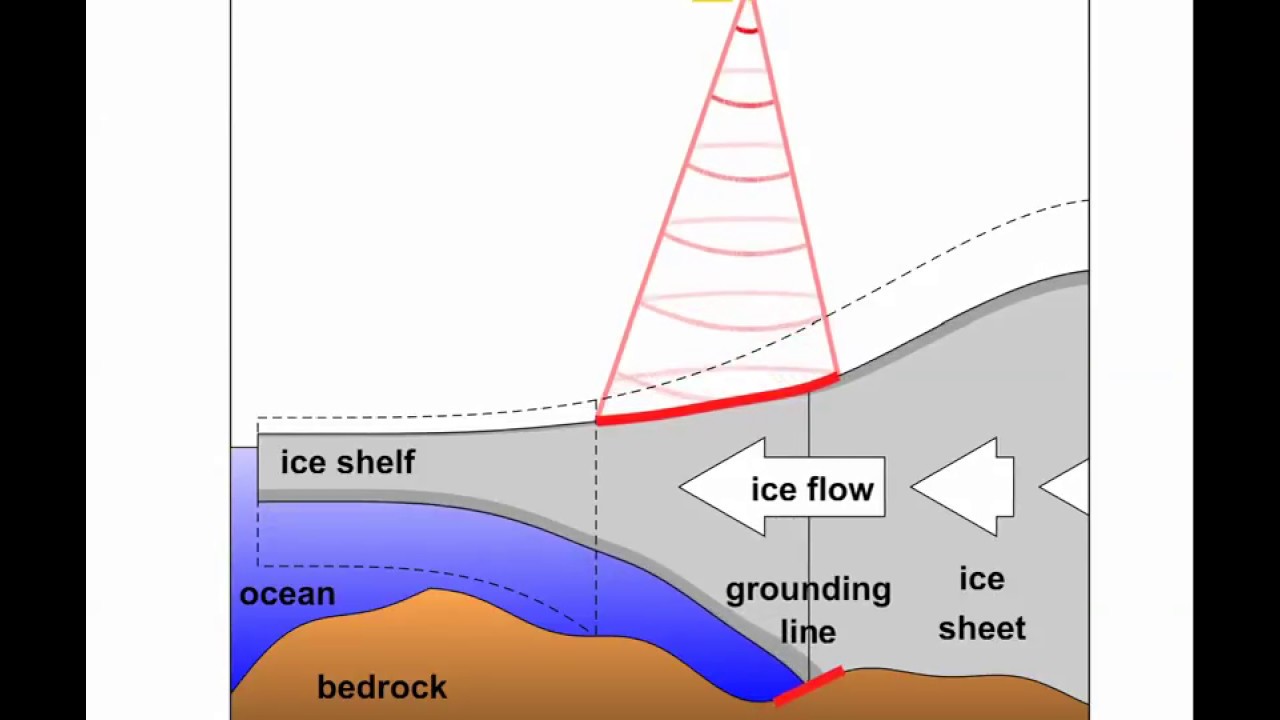

The researchers focused on a geographic feature known as grounding lines — a vertical line projected upward from the underwater edge where glacier ice finally meets with solid ocean bedrock. On one side of this line, solid sheet ice sits atop the ocean floor like a sturdy continent; on the other side, ice swoops outward like a precarious ledge, which can float more than 0.6 miles (1 km) above the ocean floor. The further inland a glacier's grounding line retreats, the faster inland ice can flow into the attached ice shelf — and ultimately into the sea.

Some grounding line retreat is expected in the centuries following an ice age, the researchers wrote, but current levels are far outpacing normal melt rates. Typically, grounding lines should retreat about 82 feet (25 meters) a year, they said. However, some of the studied regions — particularly in western Antarctica — have been receding at up to 600 feet (180 meters) per year. In total, the researchers found that, between 2010 and 2016, warming ocean temperatures melted away about 565 square miles (1,463 square km) of underwater ice from Antarctica — roughly the area of the city of London, England.

The good news is, only about 2 percent of the entire Antarctic grounding line retreated at such high rates, and some parts of the continent aren't seeing a retreat at all. The bad news is, these if these accelerated rates don't slow down, they could lead to parts of Antarctica's inland ice sheet totally collapsing into the ocean. According to a 2017 study, such a collapse would likely put the world on track for experiencing worst-case-scenario sea level rise of 10 feet (3 meters) by 2100.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Further study of Antarctica's grounding lines is needed to understand why some regions of the continent are receding so drastically while others stand still. According to the researchers, the methods developed for their new study should make future observations of this invisible melting ice much easier.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.