Most Distant Star Ever Seen Is 9 Billion Light-Years Away

Astronomers have observed a star that's so far away, its light took 9 billion years to reach us here on Earth — about 4.5 billion years before our solar system even existed.

And while scientists have peered at even more distant galaxies, which are visible due to light from their billions of stars, this helium-burning orb, nicknamed Icarus, is the most distant ordinary individual star an Earthling has observed, according to a statement from the University of California, Berkeley. (An ordinary, or main-sequence, star is one that is still fusing hydrogen to create helium; about 90 percent of the stars in the universe fit this bill, including the sun.)

"You can see individual galaxies out there, but this star is at least 100 times farther away than the next individual star we can study, except for supernova explosions," Patrick Kelly, a former UC Berkeley postdoctoral scholar who is now at the University of Minnesota, said, referring to the explosive and superbright deaths of massive stars.

So, how'd they achieve the stellar feat? The astronomers from UC Berkeley used a method called gravitational lensing, which is based on the idea that a massive object bends the fabric of space-time itself, and the more massive the object — think a sumo wrestler on a squishy mat — the bigger that curvature. Going with that sumo-wrestler analogy, the resulting dent in the mat affects the paths of other "things" that make their way over it. Light beams, for instance, that pass over the curved space-time (or the dented mat) will be bent in particular ways. Turns out, astronomers can see the resulting distorted image from such gravitational lensing, and that image is magnified. [8 Ways You Can See Einstein's Theory of Relativity in Real Life]

For astronomers looking for that "sumo wrestler" in space, the best contender would be a weighty cluster of galaxies.

"Mass bends the paths of light that travels near it," Kelly said. "If a background source is well aligned, the cluster can bend a greater fraction of its light towards Earth, magnifying it and making it appear brighter," Kelly said.

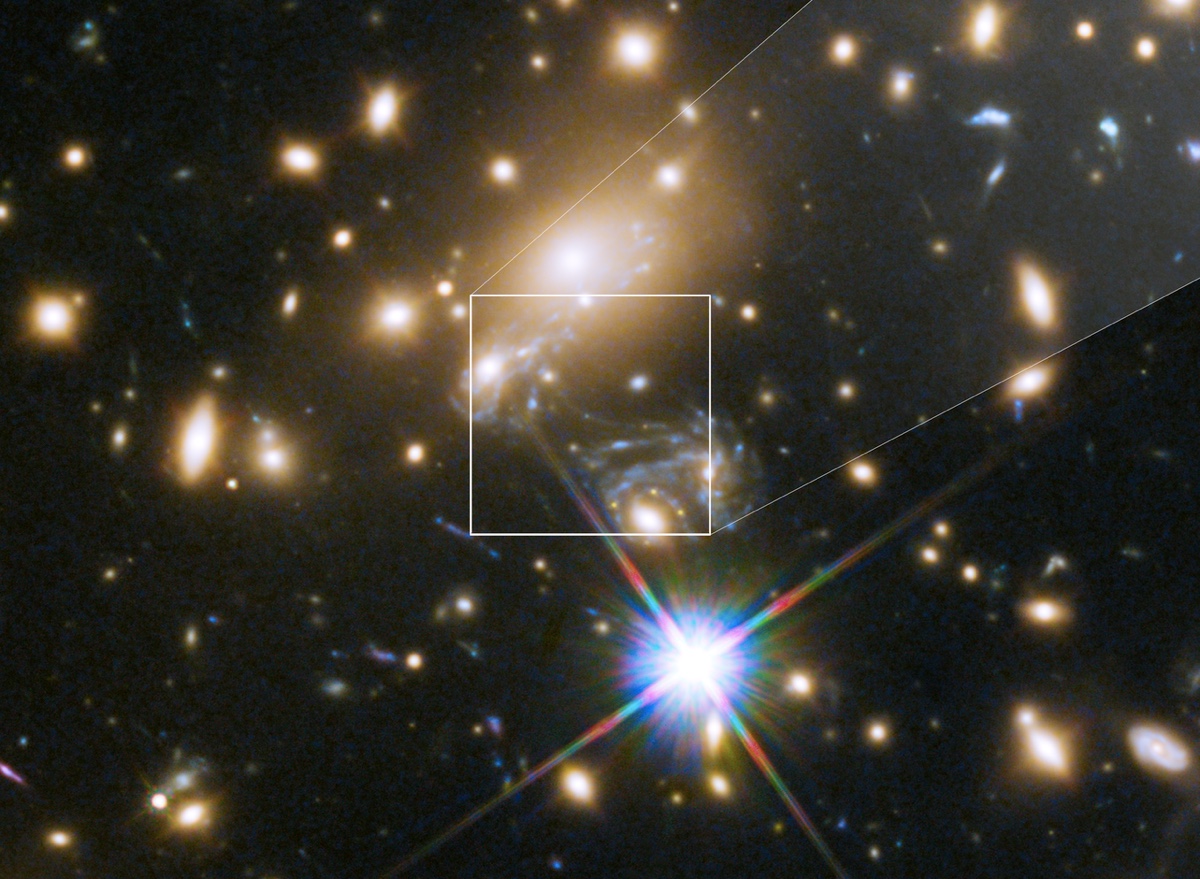

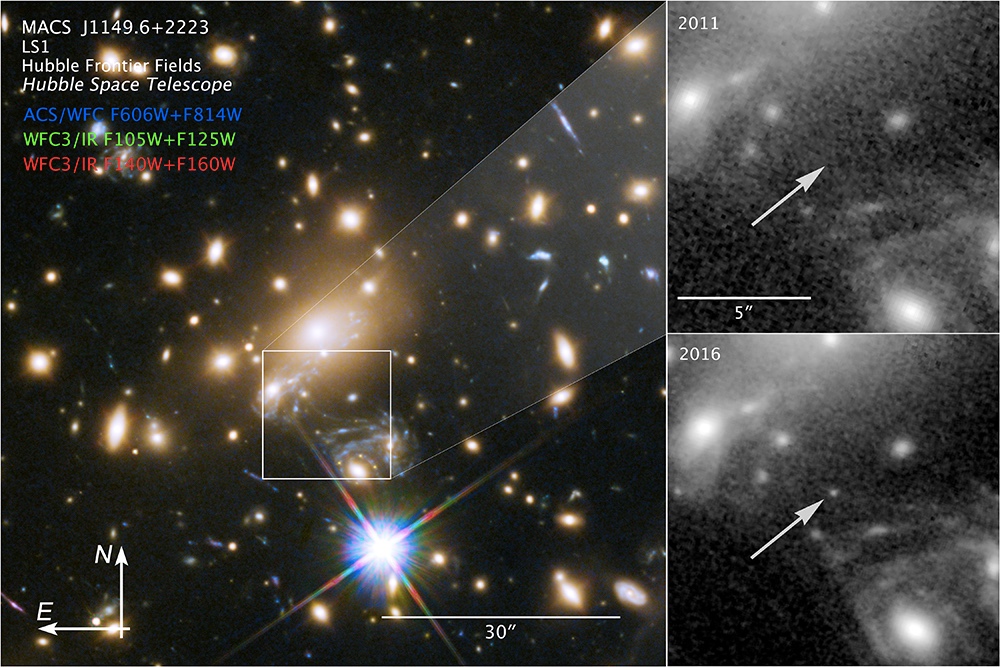

Kelly, who was the lead author on a new study describing the findings, spotted the faraway star Icarus while looking at Hubble Space Telescope images of a supernova (one he discovered in 2014) that had been shot through a gravitational lens — in this case, a galactic cluster called MACS J1149+2223 — in the constellation Leo. He was focusing on the supernova called SN Refsdal when he noticed the bright light and suspected this object was even more highly magnified than the supernova in that cluster. (MACS J1149+2223 is located 5 billion light-years from Earth.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And they were right. Another "lens" — this time, a sun-size star — had passed directly between Icarus and the Hubble Space Telescope's trained eye. [7 Everyday Things That Happen Strangely in Space]

Usually, the cluster magnifies Icarus by a factor of about 600.

"In May of 2016, however, a star in the MACS J1149+2223 galaxy cluster also temporarily became aligned," and it had the effect of boosting the magnification of Icarus to 2,000 times, Kelly told Live Science.

So, the star's gravitational lens had a multiplying effect.

"They effectively worked together — the cluster actually makes the star in the cluster act like a much more powerful lens," Kelly said.

By back-calculating how those lenses would have impacted Icarus' light, the astronomers figured out the star is a blue supergiant that's hotter and more massive than our sun. And the star may be hundreds of thousands of times brighter than our sun as well, though still so far away that gravitational lensing was key to its observation.

Kelly and his colleagues detailed their discovery online April 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to indicate the Icarus is most likley burning helium in its core, not hydrogen as was previously stated.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.