500 Million Years Ago, a Sea Worm Hosted a Poop Picnic for His Shelled Friends

About 500 million years ago, a large predatory sea worm munched on some dinner and left behind a pile of turds. Then, the worm left its burrow on the seafloor, and some shelled critters came along, poked at the droppings and died — fossilized for eternity around the poopy picnic.

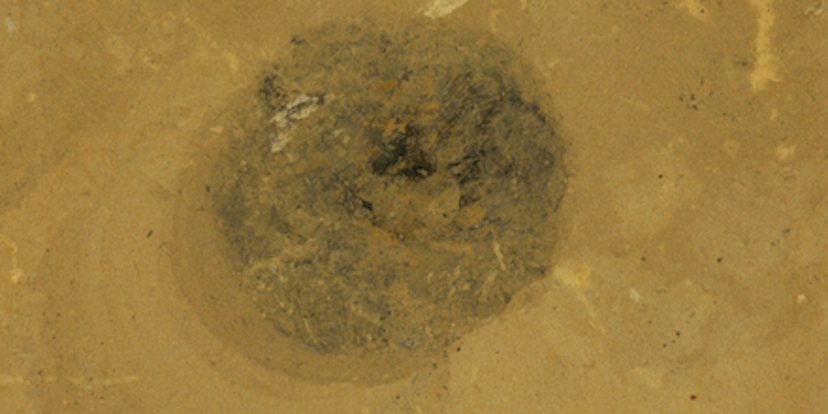

Researchers realized they were looking at a Cambrian period buffet when they discovered a fossil containing the sea worm's fossilized excrement and the remains of conically shelled sea critters known as hyoliths, according to a new study published online yesterday (April 3) in the journal Palaios.

In addition to this remarkable find, the researchers unearthed other sea worm coprolites (fossilized poop) that other Cambrian creatures, including trilobites, had fed on. These animals were "opportunistic coprovores [dung eaters] drawn to the organic-rich fecal mass," the researchers wrote in the study. [Cambrian Creatures Gallery: Photos of Primitive Sea Life]

The scientists found the ancient burrows in the Rockslide Formation of the Mackenzie Mountains in northwestern Canada. They noticed the ancient sea worm's burrows in a layer of "greenish, thinly laminated, locally burrowed, slightly [chalky] mudstone," the researchers wrote in the study.

"This is rare, because feces decompose very easily — it's not a very stable product from animals," study lead researcher Julien Kimmig, the collections manager at the Kansas University Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, said in a statement. "These were preserved because the worms lived in burrows about 4 inches [10 centimeters] deep. They were hunting out of these burrows. We have something that acted very similar to a modern Bobbit worm."

In fact, the 500-million-year-old sea worm might be a distant relative of today's Bobbit worm (Eunice aphroditois), which buries itself under sediment on the seafloor and ambushes prey.

"Bobbit worms are big worms that live in the ocean today," Kimmig said. "They prey on fish, live in burrows [and] have really big predatory appendages, and they hide in the burrow until a fish or other prey comes by — then they grab it, drag it into their burrow and eat it."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even though the researchers didn't find the remains of the mysterious Cambrian sea worm, its fossilized feces and burrows suggest that it was "likely one of the biggest predators in its environment," ranging from 6 inches to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) long, Kimmig said. It was as wide as a penny, with a 0.75-inch (2 cm) diameter, he added.

The finding shows how ancient food webs worked, but many questions remain, Kimmig and study co-researcher, Brian Pratt, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Saskatchewan, who found the fossil site in 1983 during his doctoral research, said in the statement.

"This tells us [that] animals develop a variety of feeding strategies early on, and they developed them fairly quickly," Kimmig said. "[But] we have a lot to learn about the early ecosystems and how they forced animals to adapt. When you have different predators along the open sea bottom, if you're not careful, you'll get eaten fairly easily."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.