Scientists Find Very Young Cells in Even Very Old Brains

Your brain keeps making new nerve cells, even as you get older.

That's a big deal. For decades, researchers believed that aging brains stop making new cells. But recent research has offered strong evidence to the contrary, and a new paper published today (April 5) in the journal Cell Stem Cell tries to put the notion to bed entirely. Aging brains, the researchers showed, produce just as many new cells as younger brains do.

"When I went to medical school, they used to teach us that the brain stops making new cells," said lead study author Dr. Maura Boldrini, a neurobiologist at Columbia University. [10 Surprising Facts About the Brain]

But, Boldrini told Live Science, researchers began to suspect that was wrong: Studies in mice showed that even the older mice produced new nerve cells. And early studies in humans started to turn up similar results.

This study, though, is the first to thoroughly track the brain's cell production over the course of a typical human lifetime.

Boldrini and her colleagues studied 28 brains that came from the corpses of healthy people ages 14 to 79. And these donated brains were unusual in this kind of research: The researchers knew a whole lot about them.

("Healthy" is, of course, a relative term. The brains were dead. But they didn't show evidence of any major disorders. And they didn't come from drug users. They also didn't come from people who had been treated with antidepressants, which researchers believe can actually stimulate cell growth.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They came from a library of donor brains assembled at Columbia that had all been preserved using the same methods and that had detailed medical histories attached to them.

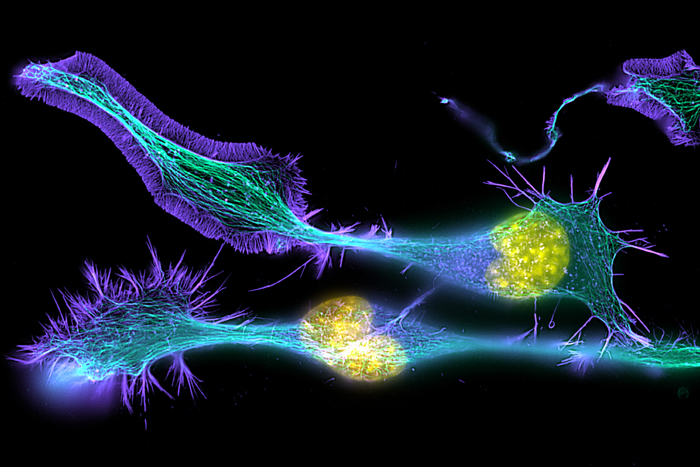

Boldrini and her colleagues sliced the hippocampi, an area of the brain important for learning and memory, into slivers, and counted the number of newly formed cells — those that had yet to fully mature — under a microscope.

This part turned out to be especially challenging. "People who study mice with tiny brains, it's easy," Boldrini said. "You cut them up, look at the cells, and you count them."

But human brains are bigger and more complicated. Boldrini and her colleagues used specialized computer software to count the cells under a microscope.

The older brains weren't completely unchanged. While they had as many new cells as younger brains, they seemed to be making fewer new blood vessels, and not forming new connections between brain cells as quickly.

It's important to note that the science of brain-cell formation in old age is far from mature. As recently as March 7, a paper published in the journal Nature challenged this idea that older brains keep making new nerves. In studies of sick and healthy brains, the authors found a sharp decline in the production of new brain cells, beginning around adolescence, with no new nerve cells detected in the brains of adults.

Boldrini suggested that the difference between her team's results and those of the Nature paper could have been traced to the brains the different groups were examining, and the methods used to examine them. The brains described in the Nature paper, she said, came from a wider range of people with different health conditions, including epilepsy, and may have been preserved using different techniques. Those preservation techniques, she said, may have destroyed evidence of new cells.

Because all the "healthy" brains in the Columbia study exhibited new cell growth, Boldrini and her team suggested that the continued ability to produce new cells in the hippocampus might be a key feature of brains that remain healthy into old age.

Originally published on Live Science.