Could Beasts Like Frankenstein's Monster Exist in Real Life?

WASHINGTON — People are fascinated by monstrous creatures, and popular culture and folklore are populated by bizarre beasts, from electrically reanimated corpses and giant, hairy humanoids to blood-guzzling vampires and amorous fish-men.

Are any of these monsters even remotely possible in the real world?

Not every monster is scientifically plausible, but many do have their foundations in the natural world's real-life "monsters," a group of experts reported here March 31 during the Future Con panel "Ack, Real Monsters." They weighed in on what makes a monster and introduced the audience to some terrifying examples of animals that are just as strange and alarming as their fictional counterparts. [Our 10 Favorite Monsters]

So, what qualifies as a "monster," anyway? That was a question asked by panelist Tina Hesman Saey, a geneticist-turned-writer at Science News. Interpretations vary, but a study from the 1970s on the population density of aquatic monsters in Scotland's Loch Ness was quite specific on the subject, with the authors insisting that, to be considered a "monster," a creature would have to weigh at least 220 lbs. (100 kilograms), according to panelist Bethany Brookshire, a staff writer with Science News for Students.

"Anything smaller would not be 'suitably monstrous,'" Brookshire said.

Who's the real monster?

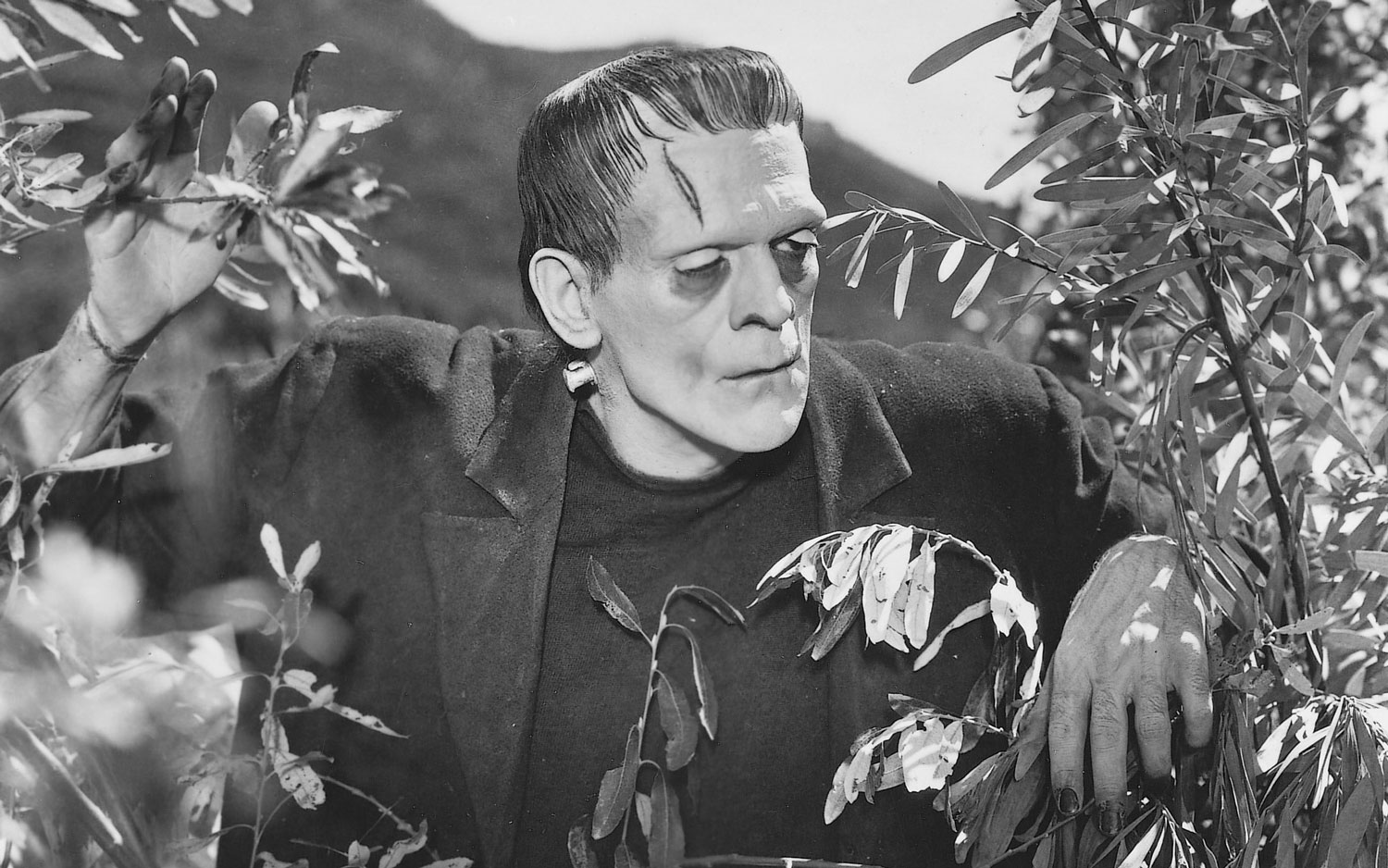

One of the more famous and enduring monsters introduced by the panel was Frankenstein's monster (often erroneously referred to as "Frankenstein," the name of its scientist creator). It originated in the book "Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus," written by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and published in 1818.

Stitched together from stolen body parts and shocked to life with electricity, the creature horrifies its master and is shunned and rejected by the people it meets. However, Dr. Frankenstein's ghoulish actions arguably make him much more of a monster than the hapless being he brought to life, Brookshire added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for the "science" that created the monster, electricity can certainly interact with isolated body parts to generate a muscular response, in a process known as galvanism, the panel members explained. But electrically generating life where none exists is simply not possible, they said.

In the novel, Dr. Frankenstein creates the monster out of bits and pieces of organs from an array of corpses. However, transplanted organs and body parts are often rejected by their host bodies; a creature whose entire body is made up of bits and pieces from an array of corpses would need to have a dramatically suppressed immune system so that all those body parts wouldn't reject one another, Saey told the audience. In fact, its immune system would have to be suppressed to the point where the creature could survive only in a protective bubble, she added.

"Heroic peeing"

But while Frankenstein's monster was abhorred, some monsters are thought to be quite charismatic — such as vampires, according to panelist Susan Milius, another writer for Science News. Much like mosquitoes, vampires have an all-blood diet. But if their habits were truly like those of the bloodsucking insects, people would probably see them as a lot less glamorous, Milius suggested.

"If you talk to scientists who study mosquitoes, you spend a lot of time listening to their thoughts on heroic peeing," she said. "If we brought more biological realism to vampire shows, they'd be peeing while they're eating." (The pesky insects must urinate while feeding on blood to rid themselves of excess fluid.)

But the monsters that are even more amazing than vampires are zombies, according to panelist Kali Holder, a veterinary pathology fellow at Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. And unlike some other monsters, real-life zombies abound in the natural world, created by parasitic creatures that hijack other animals' brains and turn them into mindless slaves with no control over their own bodies, save to fulfill the whims of their controllers, Holder said. [Mind Control: Gallery of Zombie Ants]

Lancet liver flukes (Dicrocoelium dendriticum), for example, lead ants on a forced march up blades of grass, where they're likely to be eaten by a sheep, because that's where the fluke needs to be to complete its life cycle, Holder explained. Another parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, affects rats, sending them scurrying out into the open instead of along walls and corners, and tweaking their brain chemistry so they're attracted to the smell of cat urine, she said. (T. gondii can reproduce only inside the feline's gut.)

Viruses are also very, very good at changing the behavior of the animals they infect, as are certain types fungus in the Ophiocordyceps genus, and wasps that perform a type of delicate brain surgery on cockroaches so they can steer them with the roaches' own antennae, the panelists told the audience.

A final question from the audience targeted what might be the next monster trend that we'd see in pop culture. Saey opted for portrayals of Bigfoot, while Milius argued that fungal spores had "great potential." And while Holder had already proclaimed her allegiance to Team Zombie, she enthusiastically cast her vote for more sea monsters, perhaps along the lines of the humanoid fish-man in the recent film "The Shape of Water" but with more of a deep-sea body plan.

"We need something with tentacles," she said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.