Glass 'Bread Crumbs' Could Lead the Way to Missing Crater

A spattering of miniscule glass "beads" found in the mountains of Antarctica may lead the way to an 800,000-year-old meteor impact crater.

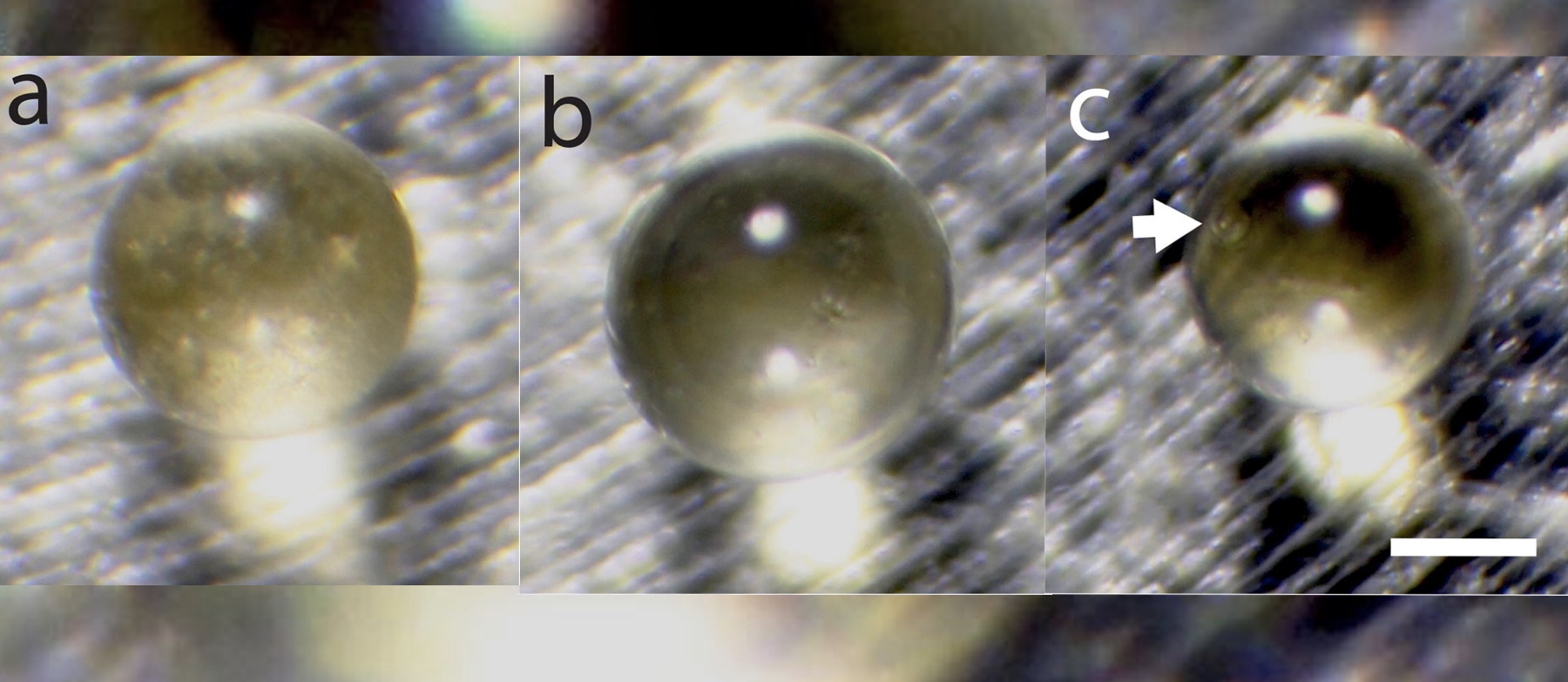

The tiny spheres, known as microtektites, are each no wider than a human hair. They were sprayed into the atmosphere by a 12-mile-wide (20 kilometers) meteor that hit the Earth and left a field of glassy debris over at least 8,700 square miles (14,000 square km) of Australia and southern Asia.

The crater formed by this impact, however, has never been found. The discovery of the tiny glassy debris from the impact in Antarctica could help lead the way to the mysterious impact point, researchers reported May 1 in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. The analysis of the potassium and sodium inside the spherules suggests they're the debris thrown farthest from the crater, study leader Matthew Genge, a senior lecturer in Earth and planetary science at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

When large meteors hit the Earth's crust, the impact melts rock and heaves it skyward, resulting in glassy objects called tektites that can scatter over large distances. Tektites from the mysterious impact of 800,000 years ago have been found from Australia to Southeast Asia and even in sediments in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Genge and his colleagues wrote in their new paper. [Crash! 10 Biggest Impact Craters on Earth]

The new study, however, focuses on the teeniest version of this glassy debris, microtektites found in Victoria Land, Australia. Researchers suspect the meteor impact happened somewhere in Southeast Asia, perhaps in what is today Vietnam, which would mean the microtektites traveled a whopping 6,835 miles (11,000 km) or so.

Researchers analyzed 52 of the pale yellow, bizarrely smooth spherules, finding that their composition overlapped with that of tektites found closer to the hypothetical impact site, but with some important differences. In particular, the levels of potassium and sodium in the Antarctica samples were lower compared with tektites from closer in the debris field.

Potassium and sodium concentrations drop dramatically under hot conditions, study co-author Matthias Van Ginneken of Vrije University in Belgium said in the statement. The microtektites in the study were thus hotter than the rest of the tektite debris, the researchers concluded. And hotter debris also travels farther from the point of impact.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Following the bread-crumb trail of debris from hotter to cooler should lead us to the crater," Van Ginneken said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.