85,000-Year-Old Finger Bone May Rewrite the Story of Human Migration Out of Africa

A sliver of bone the size of a Cheeto may radically revise our view of when and how humans left Africa.

The 85,000-year-old fossilized human finger bone, unearthed in the Saudi Arabian desert, suggests that early humans took completely different routes out of Africa than was previously suspected, a new study finds.

The finding is the oldest human fossil on record unearthed outside of Africa and the Levant (an area encompassing the Eastern Mediterranean, including Israel), and the oldest human remains uncovered in Saudi Arabia, the researchers said. [7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot]

Until now, many scientists thought that early humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago and then hugged the coastline, living off marine resources, said study senior researcher Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

"But now, with the fossil finger bone from the site of Al Wusta in Saudi Arabia, we have a find that's 85,000 to 90,000 years old, which suggests that Homo sapiens is moving out of Africa far earlier than 60,000 years ago," Petraglia told reporters at a news conference. "This supports a model not of a single, rapid dispersal out of Africa 60,000 years ago, but a much more complicated scenario of migration."

Definitely a human

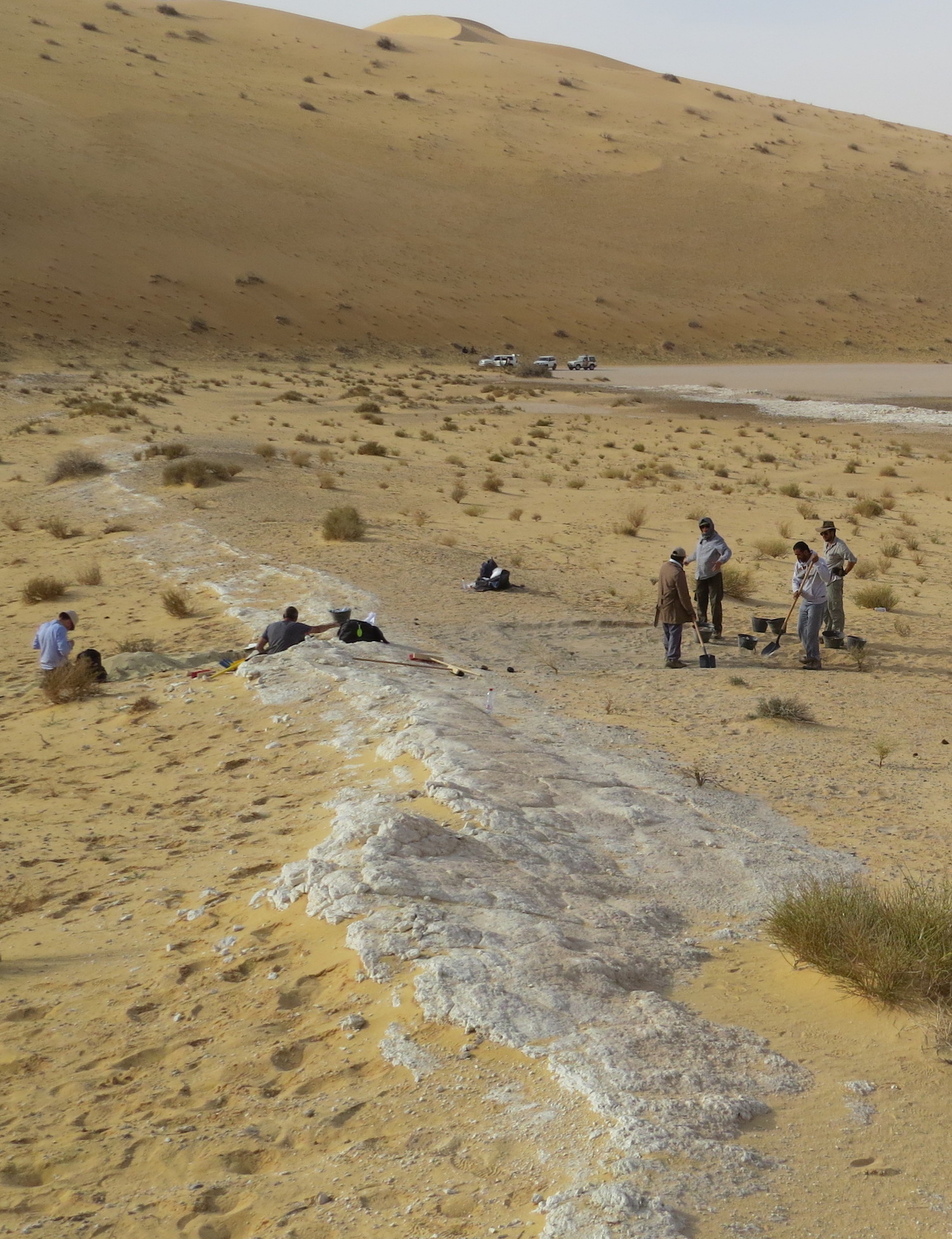

Study co-researcher Iyad Zalmout, a paleontologist with the Saudi Geological Survey, found the remarkable 1.3-inch-long (3.2 centimeters) fossil finger in the Nefud Desert in 2016, said study lead researcher Huw Groucutt, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford in England.

A basic visual examination suggested it belonged to Homo sapiens, Groucutt said. That's because humans have long and thin fingers compared with Neanderthals, who were also alive at that time, he said. However, the researchers had their colleagues do a micro-computed tomography (CT) scan to make sure.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After comparing the CT scan of the newfound fossil to several other species that have human-like fingers, including gorillas, Old World monkeys, Australopithecus afarensis, Australopithecus sediba and Neanderthals, the researchers determined it was human — likely the middle part of a human's middle finger, they said.

"All of these studies agreed that the fossil belonged to Homo sapiens," Groucutt said at the news conference. "The shape of Homo sapiens finger bones is just quite distinct compared to other species."

The finger bone likely belonged to an adult, but it's unclear if that individual was a man or a woman, he added. In addition, because the bone has mineralized into a fossil and has sat in an arid environment for thousands of years, it likely doesn't have any DNA left in it, Groucutt said.

Hippos and stone tools

Al Wusta may be a desert now, but about 85,000 years ago, it had a freshwater lake frequented by many animals, including hippopotamuses, Pelorovis (a now-extinct genus of wild cattle) and Kobus (a genus of African antelope), whose fossilized remains were found at the site. Moreover, the researchers uncovered human-made stone tools there.

But why were these African animals in Arabia at this time? It's possible that monsoonal rains, which had transformed the region into a humid, semiarid grassland crisscrossed with rivers and lakes, drew these animals from sub-Saharan Africa to Arabia, Petraglia said. [In Photos: Paleolakes Dot 'Green Arabia']

"And, of course, hunters and gatherers would have been following those animals," Petraglia said.

In fact, the remains of the Nefud Desert's other ancient lakes may sport even more evidence of early Homo sapiens who were likely following big-game animals out of Africa, the researchers said.

"We are one of two projects in Arabia that are working on this time period," but satellite images show that there are about 10,000 paleo lakes in the region, Petraglia said.

Out of Africa

This new finding is one of many that are helping scientists map early humans' trek out of Africa. In January, another group of researchers announced the discovery of a 194,000-year-old modern human jawbone in Israel's Misliya Cave, Live Science previously reported.

However, even though the finger bone is much younger than the jawbone, it's still a momentous find, Groucutt said.

"Humans repeatedly expanded into the Levant, into the doorstep of Africa, but we don't know what happened beyond that area," Groucutt said. While the Levant was then a wooded area with winter rainfall, Al Wusta, about 400 miles (650 kilometers) away, was a grassland that received summer rain. If ancient humans could leave one environment for the other, they must have been quite adaptable, the researchers said.

Moreover, the date of the fossil finger jibes with other archaeological evidence of ancient humans uncovered outside of Africa, the researchers said, including 70,000-year-old H. sapiens fossils found at Tam Pa Ling in Laos; 68,000-year-old H. sapiens teeth found in the Lida Ajer cave, in Sumatra; 80,000-year-old H. sapiens teeth from the Fuyan Cave in China; and the 65,000-year-old documentation of human presence in Australia.

"This discovery for the first time conclusively shows that early members of our species colonized an expansive region of southwest Asia and were not just restricted to the Levant," Groucutt said in a statement. "The ability of these early people to widely colonize this region casts doubt on long held views that early dispersals out of Africa were localized and unsuccessful."

The study was published online today (April 9) in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.