Prehistoric Sea Monster Was Nearly the Size of a Blue Whale

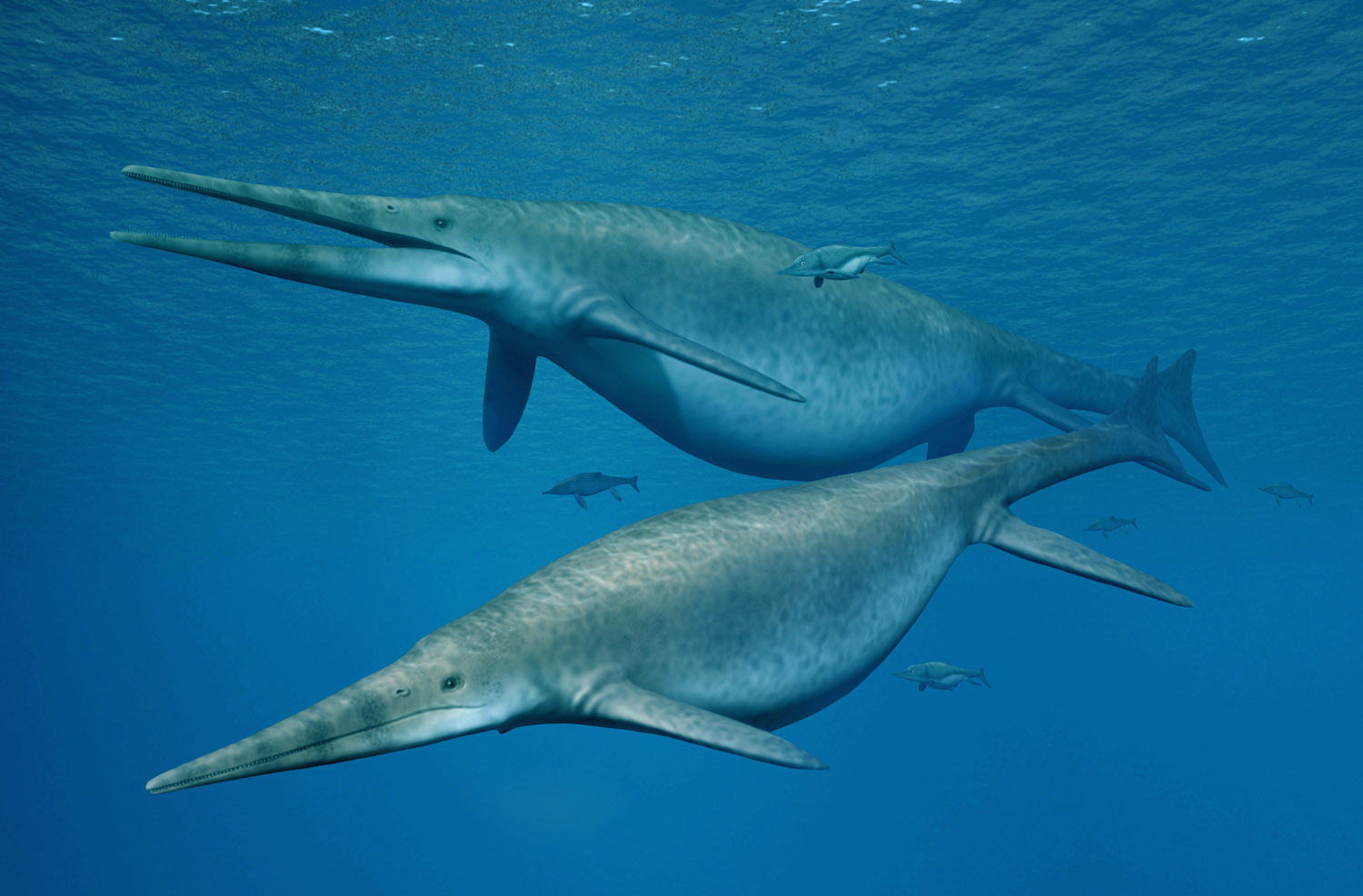

About 205 million years ago, a ginormous sea monster — so large it was nearly the size of a modern blue whale — swam through the ocean, fueling its colossal body by preying on prehistoric squid and fish, a new study finds.

The recent discovery of this creature's immense jawbone has helped researchers identify a previously unknown species and to solve a nearly 170-year-old mystery. In 1850, beachgoers in southern England found Late Triassic fossils by the shore that were so massive, they were thought to be the limb bones of giant dinosaurs, such as the long-necked sauropods.

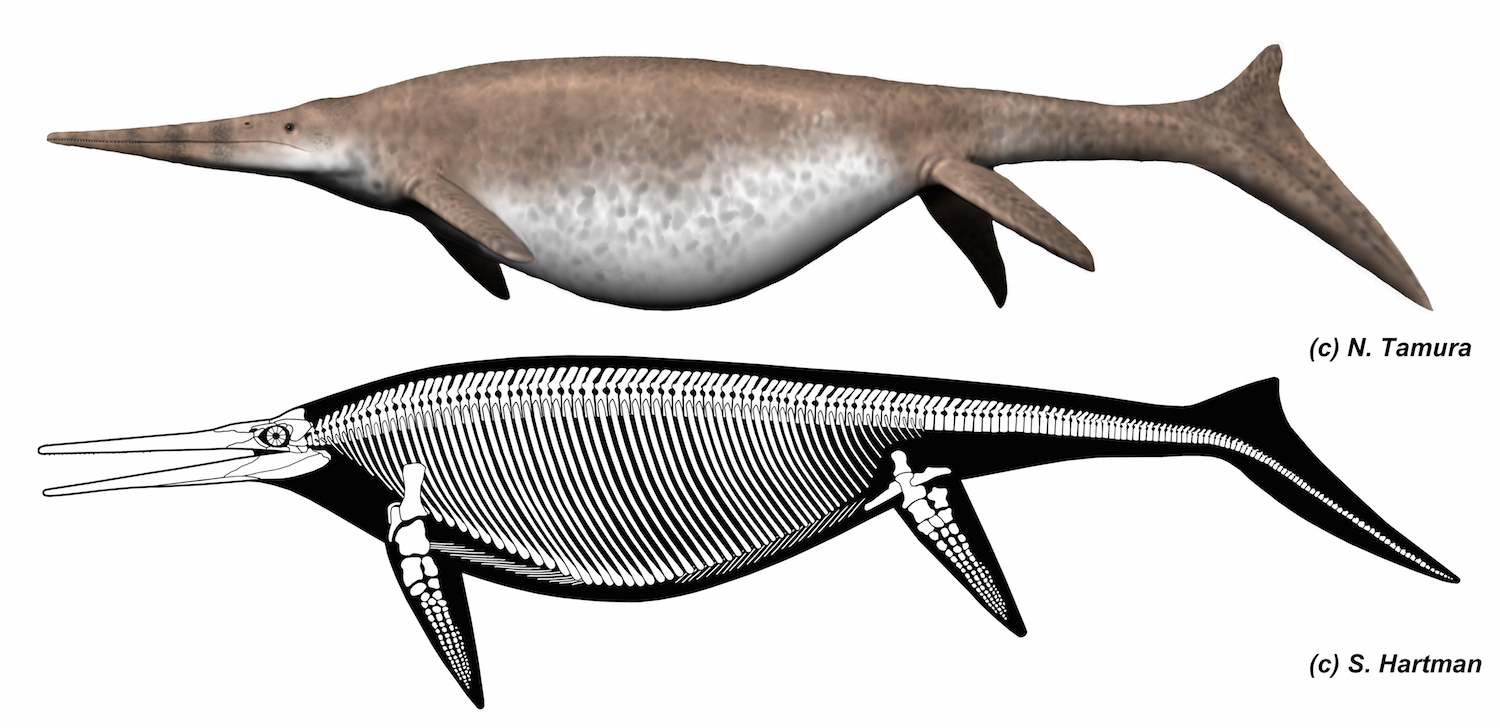

But now, thanks to the newfound jawbone finding, researchers think those bones likely belonged to the largest-known ichthyosaur (ik-thee-o-saur) ever found. These creatures, marine reptiles resembling modern-day dolphins, went extinct at the end of the dinosaur age, around 66 million years ago. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

In May 2016, while walking on a beach in Lilstock, England, study co-researcher and fossil collector Paul de la Salle found pieces of a jawbone that, when pieced together, measured an astounding 3.1 feet (96 centimeters) long.

After connecting with ichthyosaur researchers, including Dean Lomax, a paleontologist at The University of Manchester in England, and Judy Massare, professor emerita of geology at SUNY College at Brockport in New York, de la Salle determined that the specimen belonged to a giant ichthyosaur known as a shastasaurid from the Triassic, which lasted from 251 million to 199 million years ago. The researchers have yet to name the new species and are calling it the Lilstock specimen for now.

Based on the jawbone's length, the researchers estimated that the Lilstock ichthyosaur measured more than 85 feet (26 meters) long, making it the largest ichthyosaur on record — up to 25 percent larger than the previous shastasaurid record holder, Shonisaurus sikanniensis, a 69-foot-long (21 m) beast found in British Columbia, the researchers said.

"The Shonisaurus specimen is much more complete, including the back half of the skull, most of the backbone and ribs, some of the shoulder bones and part of the tail," Massare, the study's co-researcher, told Live Science. "A comparison with the back of the Shonisaurusjawindicates that our specimen is larger, but we know much less about it because it is just one bone."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The world was a very different place when the Lilstock ichthyosaur was alive. During the Late Triassic, the giant supercontinent, called Pangaea, was beginning to split up, said Lomax, the study's lead researcher. "What is now the United Kingdom would have been surrounded by a warm, tropical sea," he noted. "On land, it was very hot and dry, with desert-like conditions."

The jawbone discovery reveals more about the animals that lived in England's ancient tropical seas. And it's also solved the mystery of the so-called dinosaur bones.

"Due to Paul’s discovery, we have managed to unlock the mystery of these giant 'dinosaur limb bones' — they are bones from the mandible of giant ichthyosaurs," Lomax said.

The study was published online today (April 9) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.