Chimps Seen Sucking Brains from Monkeys' Heads

Chimpanzees are primarily plant eaters, though they enthusiastically eat animals when they can catch them, and monkeys are an especially desirable treat. But once the snack is in hand — and with so many delicious body parts to choose from — which do the predatory primates eat first?

Wonder no longer. Scientists have discovered that it all depends on the age of the unfortunate prey.

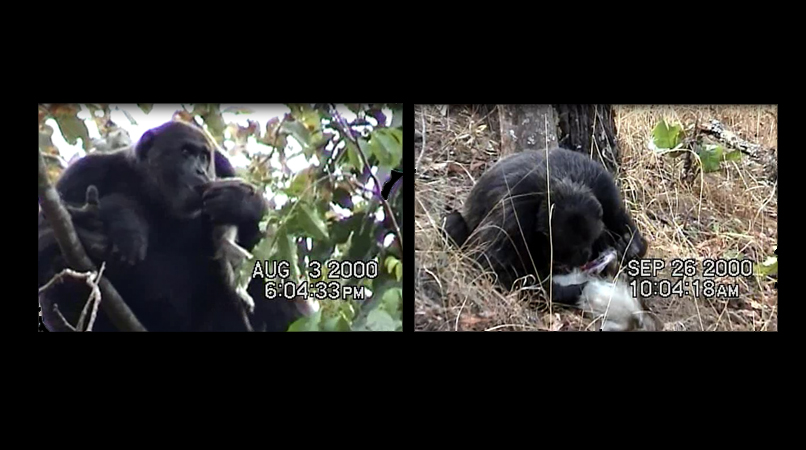

Researchers recently filmed chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in Tanzania's Gombe National Park excitedly munching on monkeys, hoping to learn more about the chimps' carnivorous eating habits. Whenever older monkeys were on the menu, chimps tended to initially harvest the organs — particularly the liver, which is rich in fat, the scientists reported in a new study.

But if a chimp was lucky enough to catch a youngster, they were almost certain to go straight for the tender, savory and nutrient-packed brain, biting right through the fragile skulls and devouring the juvenile monkeys headfirst. [Image Gallery: Lethal Aggression in Wild Chimpanzees]

Meat provides chimpanzees with important nutrients that they can't get from plants — such as vitamins A and B12, zinc, copper and iron — and their enthusiasm for meaty meals demonstrates how important flesh and fat are for their diet, according to the study.

Brains, especially mammal brains, are especially high in fat. They also contain certain fatty acids that are absent from plants and are known, at least in humans, to be important for brain function and for lessening the damage from some diseases, the study authors reported.

An "undertone of enjoyment"

Prior research suggested that chimps found monkey brains to be especially desirable; the scientists cited a chimpanzee study from 1973 that noted, "The brain is the only organ for which marked preference is regularly shown, and the eating of brain tissue is always a slow, meticulous procedure with a definite undertone of enjoyment."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, the team recorded 29 incidents of monkey-eating by eight chimpanzees, and found that if the monkey was a juvenile, the chimps first went for the head 91 percent of the time. For adult monkeys, the chimps also were interested in the brains, but they cracked the skulls first only 44 percent of the time.

Whenever a chimp caught a young monkey, they all typically used a similar method to kill and eat them, biting down on the head and pulling hard, "apparently trying to remove the body from the skull," according to the study.

"Twice, we observed the possessor sucking on the head, presumably extracting the brain," the scientists wrote.

The chimps killed and consumed adult monkeys, on the other hand, using various methods, though they were most likely to begin these meals with the viscera — internal organs in the body's main cavities — which were easier to access than the adult brains.

"This has important implications for our understanding of the nutritional benefits of meat-eating among primates, and highlights the need for future studies that measure the nutritional content of specific tissues and examine which are preferentially consumed or shared," the study authors concluded.

And when it comes to meat eating, it's not just other primates that chimps find delicious; they've been known to feast on rival chimpanzees, too. On rare occasions, their cannibalistic behavior can even extend to individuals within their own social group. For instance, scientists described an incident in 2017 in which a male chimpanzee in Senegal was attacked, killed and partly cannibalized by members of his former community.

Even chimpanzee babies aren't off-limits. In 2017, in another study, scientists reported a male chimpanzee in western Tanzania stealing and cannibalizing a newborn chimp moments after its birth — the first time that this behavior had been observed in these primates. This gruesome event could explain why pregnant female chimps typically isolate themselves from their social group when it's time for them to give birth, going on "maternity leave" to protect their babies, the researchers of that study concluded.

The new findings were published online Feb. 9 in the International Journal of Primatology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.