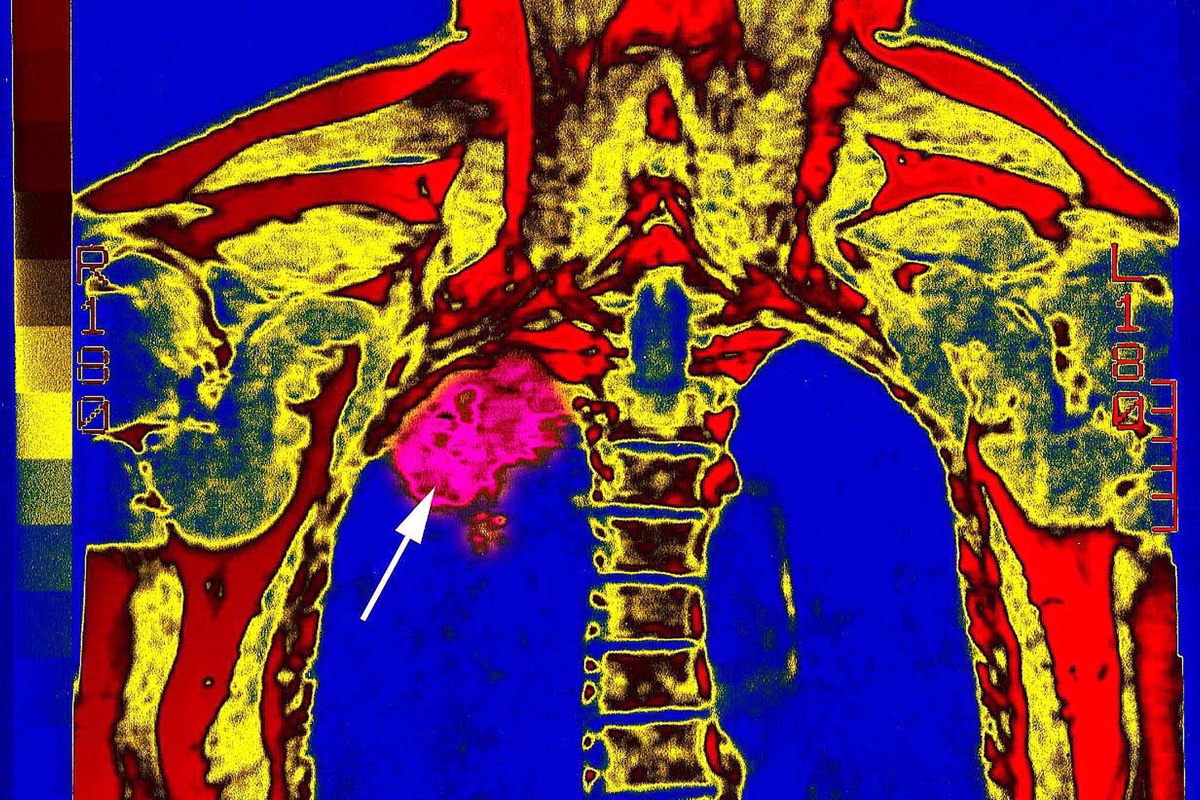

A New Lung Cancer Drug Is Shaking Up Treatment: How Does It Work?

A drug that acts on the immune system appears to help extend the lives of patients with advanced lung cancer when given alongside standard chemotherapy, a new study finds. But how, exactly, does this drug work to help fight cancer?

The study, which included more than 600 people, found that patients with a common type of lung cancer who received the so-called immunotherapy drug in combination with chemotherapy were 51 percent less likely to die over a period of 10.5 months compared with patients who received a placebo and chemotherapy (the control group).

In addition, the median "progression-free survival time," or the time patients went without their disease getting worse, was nearly nine months in the immunotherapy group, compared with five months in the control group.

The study, which was presented yesterday (April 16) at the American Association for Cancer Research meeting in Chicago, was met with excitement by experts, who said the findings may change the way some patients with lung cancer are treated.

How the drug works

The drug, called pembrolizumab and sold under the brand name Keytruda, helps the immune system detect and fight cancer cells, according to Merck, the drug's maker. Specifically, the drug makes it harder for cancer cells to "hide" from the immune system.

Usually, immune cells known as T cells detect threats in the body, such as infectious diseases, or even cancer. But cancer cells can hide from the immune system if they have a protein on their surface called PD‑L1. This protein tells T cells to stand down and not attack the cancer cells, according to Merck. The way PD‑L1 does this is by binding to another protein on the surface of T cells, called PD-1, which acts as a sort of "off switch," deactivating the T cells.

Pembrolizumab blocks this interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, and thus "allows our own immune cells to destroy the tumor cell," said Dr. Edwin Yau, an assistant professor of oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, who was not involved with the study. "By making these tumor cells sensitive to the immune system, not only do we see tumor shrinkage, but also [we see an] ongoing response due to the immune system's ability to continue to monitor for the presence of these tumor cells." [11 Surprising Facts About the Immune System]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yau noted, however, that pembrolizumab by itself works only in a minority of patients. But when given in combination with chemotherapy, the drug appears to be more effective.

"This is why the results from KEYNOTE-189 [the new study] are exciting, as the addition of chemotherapy to pembrolizumab appears to increase the number of patients who benefit from the immunotherapy," Yau told Live Science.

The results will likely change the standard treatment for patients with this type of lung cancer, known as metastatic nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer, or NSCLC, is the most common type of lung cancer. "Metastatic" means the cancer has spread beyond its original site, and "nonsquamous" means the cancer does not start in a type of cell in the lungs called squamous cells. Most NSCLCs are nonsquamous.

Instead of chemotherapy or immunotherapy alone, patients with this cancer would be given the combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy early in the course of their treatment, the new findings suggest.

Still, the drug has side effects — notably, about 5 percent of patients in the immunotherapy group experienced acute kidney problems, compared with 0.5 percent of patients in the control group. "The higher rate of renal toxicity will have to be taken into account and monitored," Yau said.

Several other questions remain, including whether patients with high levels of PD-L1 expression on their tumor cells who have already been found to benefit from this type of immunotherapy reap any extra benefits from chemotherapy, Yau said. "We eagerly continue to await longer-term follow-up of this study," he said.

The study, which was published online April 16 in The New England Journal of Medicine, was led by Dr. Leena Gandhi, director of the Thoracic Medical Oncology Program at Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.