Hurricane Irma Turned the Everglades into a Tree 'Graveyard,' NASA Lasers Reveal

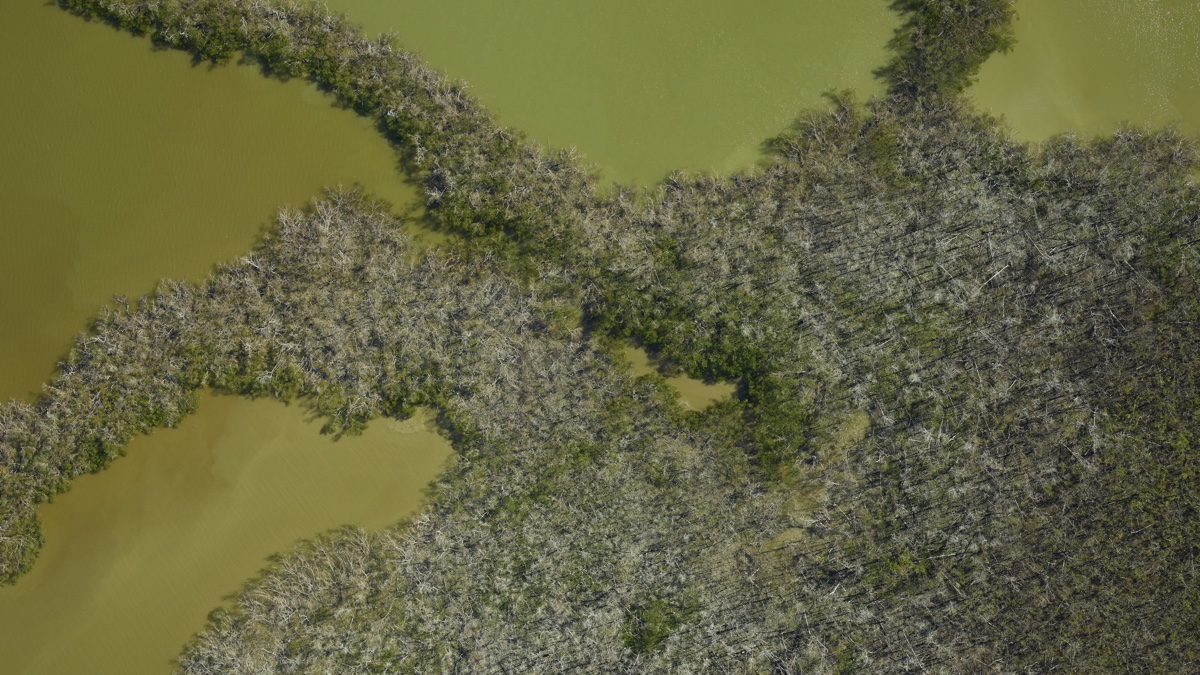

VIENNA — Hurricane Irma turned the vast mangrove forests of the Everglades into a tree graveyard, new NASA images reveal.

The mass tree casualties were revealed by light detection and ranging (lidar) surveys of the iconic swampland both before and after the massive storm. Irma shaved several feet off the average height of the canopy, and 60 percent of the mangrove forests had been badly damaged, NASA researchers found. [Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm]

"The only areas where there were less damages in the post-hurricane environment were the forests that were submerged along the margin of the water as the sea-level surge came in from the hurricane and actually protected those mangrove trees," Douglas Morton, an Earth scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, told reporters last Wednesday (April 11) at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union here in Vienna.

Lidar images

Morton and his team use lidar surveys to study how forests change when trees fall and gaps form in the canopy. Lidar is a remote sensing technique that allows scientists to essentially see through slices of the forest canopy, from the tallest trees to the shortest shrubs and grasses. NASA's low-flying planes equipped with lidar scanners send out up to 500,000 laser pulses per second to capture 3D images of the landscape below.

"With this airborne set of tools, we're able to make detailed three-dimensional maps across large portions of forest regions that have been inaccessible to us," Morton said.

However, scientists never had this type of high-resolution airborne lidar data from before and after a hurricane, Morton said. His team had already collected data for the Everglades in March 2017, covering 500 square miles (1,300 square kilometers) of wetlands. So when Hurricane Irma hit on Sept. 10, the researchers took the opportunity to fly over the same area again in December.

Just how bad was the carnage?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hurricane Irma's wind speeds of more than 140 mph (225 km/h) ripped trees out of the ground and sheared limbs off trees across the Everglades.

Morton said that about 40 percent of the area they could see in the images was covered with gaps from broken branches and fallen trees. A NASA announcement about the findings noted that the average height of the canopy shrank by 3 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 meters) because of the damage.

"This degree of damages to the coastal mangroves in Florida is quite high," Morton told Live Science.

There could be some serious consequences beyond the Everglades if the mangrove trees do not recover, Morton said. One region that may be in particular trouble is theTen Thousand Islands area.

"The coastline will change, as mangrove trees stabilize sediment that helps create islands," Morton said.

Without these islands, the tides flow differently and storms could affect inland ecosystems more severely, Morton added.

He added that changing coastlines will also affect the way the area is impacted by rising sea levels.

The same researchers had scanned the rainforests of Puerto Rico before the island was struck by both Irma and later Hurricane Maria. This week, the team returns to Puerto Rico for a post-storm survey to assess the damage and potentially identify landslide threats, according to NASA.

Original article on Live Science.