Humans Probably Practiced Brain Surgery on This Cow 5,000 Years Ago

About 5,000 years ago, humans used crude stone tools to puncture a hole in a cow's head, making it the earliest known instance of skull surgery in an animal.

It's unclear whether the cow (Bos taurus) was alive or dead when the operation took place, but if it was alive, the animal didn't survive for long, given that its skull shows no signs of healing, researchers said in a new study.

However, the intent of the surgery remains a mystery. If the operation — known as trepanation, a primitive type of brain surgery — was meant to save the cow, it would be the oldest known evidence of veterinary surgery on an animal, said the study's lead researcher, Fernando Ramirez Rozzi, director of research specializing in human evolution at France's National Center for Scientific Research in Toulouse. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

It's also possible that Neolithic humans were simply using the cow to practice trepanation, "in order to perfect the technique before applying it to humans," Ramirez Rozzi and study co-researcher Alain Froment, a biological anthropologist at the Museum of Man, an anthropology museum in Paris, wrote in the study.

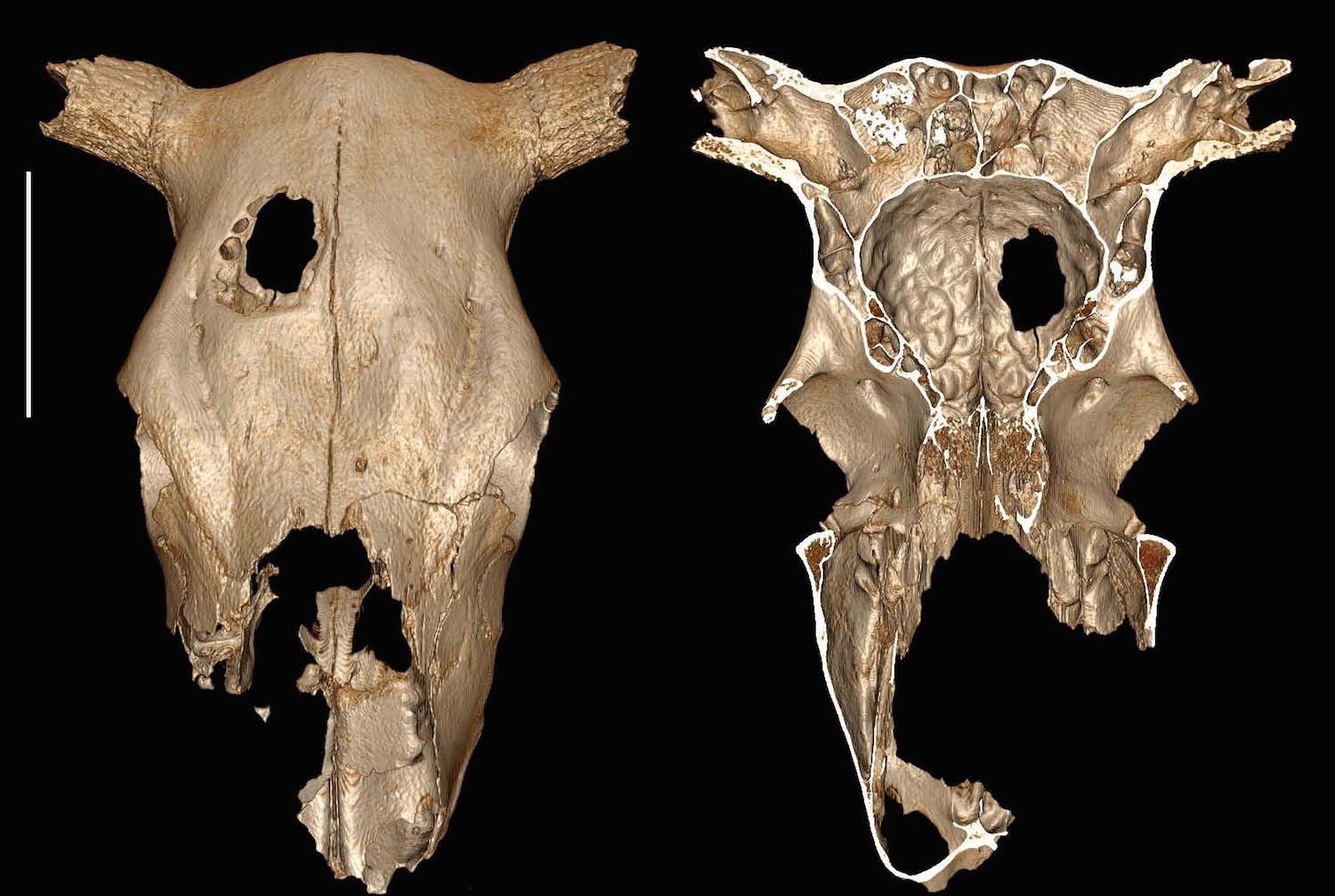

Researchers unearthed the ancient cow skull during an excavation lasting from 1975 to 1985 at the Neolithic site of Champ-Durand in Vendée, a region on the Atlantic coast of western France. An analysis showed that the cow skull dated to sometime between 3400 B.C. and 3000 B.C., and that the animal was clearly an adult, the researchers found.

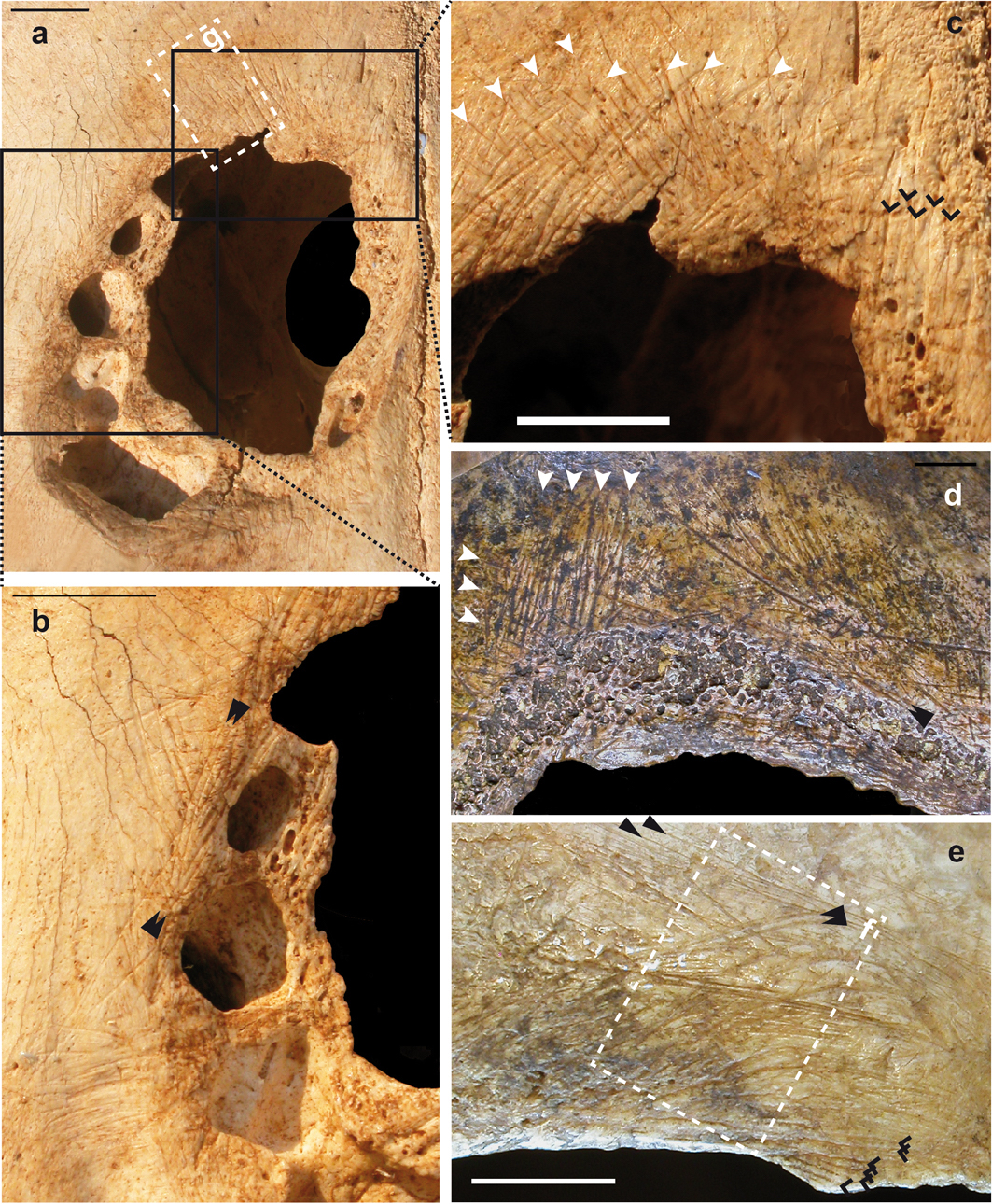

When past archaeologists first looked at the nearly complete cow cranium, they thought another cow must have caused the gouge. But the hole — which is 2.5 by 1.8 inches (6.4 by 4.6 centimeters) — was so peculiar that one of the original researchers asked Ramirez Rozzi and Froment to take a second look at it in 2012.

"At that time, we looked, and very quickly, we saw that it was trepanation in the cow skull; it was not a goring at all," Ramirez Rozzi told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If another animal had gored the cow, the violent blow would have caused fractures or splintering around the wound, the researchers said. And "no evidence of such a fracture, either internally or externally, can be seen," the researchers wrote in the study. Nor does the hole look like it was caused by an infectious disease, such as syphilis or tuberculosis, Ramirez Rozzi and Froment noted.

While using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers saw cut marks around the hole in the cow's head that looked eerily similar to scrape marks seen on the skulls of human trepanation patients, Ramirez Rozzi said.

The earliest evidence of trepanation in a human skull dates to the Mesolithic period, which lasted from about 8000 B.C. to 2700 B.C., the researchers said. Archaeologists have several ideas about why ancient people would scrape or drill a hole into a skull. Perhaps the technique was meant to solve a medical condition, such as epilepsy, or maybe it was part of a ritual, the researchers said.

In the cow's case, it's not clear why Neolithic people would have gone the extra mile to save a cow with some kind of medical disorder, Ramirez Rozzi said. It's more likely that these ancient people were using the cow's skull for trepanation practice, he said.

The study was published online today (April 19) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.