These 'Dirty' Thunderstorms Fill the Sky with As Much Smoke As a Volcanic Eruption

Wildfires can fuel "dirty" thunderstorms that fill the stratosphere with as much smoke as a volcanic eruption.

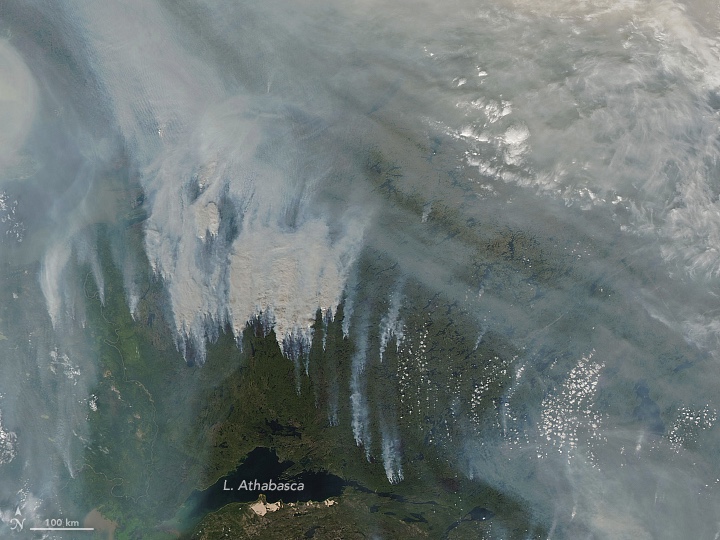

That revelation comes from a study on the biggest fire-fueled thunderstorm event on record, which occurred on the night of Aug. 12, 2017, in British Columbia, Canada.

Last year was a record breaker for wildfires in that region. And on that August evening, the heat from fires burning in relatively remote forests in British Columbia combined with the right atmospheric conditions to generate a series of four thunderstorms in a 5-hour period. [Infographic: Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom]

These fire storms are called pyrocumulonimbus storms, or pyroCbs. Like regular thunderstorms, they produce lightning and are very tall. But pyroCbs are also filled with smoke.

"You end up with this very dirty thunderstorm," David Peterson, a meteorologist with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory who presented his findings last week at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna. "Essentially, this is a giant chimney taking smoke from the surface to high altitudes, at least to aircraft-cruising altitudes."

The enormous smoke plume from the pyroCbs in British Columbia drifted over Europe and then eventually encircled the entire Northern Hemisphere. Using satellite data, Peterson's team observed the signal from this smoke in the lower stratosphere — the second layer of Earth's atmosphere, above the troposphere — for several months later.

"This was the mother of all pyroCbs," Peterson said. "Normally, when you see something like this, you think volcanic eruptions — that's what normally puts a lot of material into the stratosphere — but it's all coming from these wildfire-driven thunderstorms."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For comparison, the explosive 2008 eruption of Mount Kasatochi, an island volcano in Alaska, sent about 0.7 to 0.9 teragrams (nearly 1 million tons) of aerosols — tiny, suspended particles — into the stratosphere, Peterson said. For months afterward, people around the Northern Hemisphere documented unusually colored sunsets, thanks to the sulfate aerosols and ash the volcano injected into the atmosphere.

Peterson's team estimated that the British Columbia pyroCb event sent about 0.1 to 0.3 teragrams (about 200,000 tons) of aerosols into the stratosphere — which is comparable to the amount seen with a moderate volcanic event, and more than the total stratospheric impact of the entire 2013 fire season in North America, he said.

It's well known that catastrophic volcanoes can influence the global climate. The huge 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, one of the largest in living memory, lowered temperatures around the world by an average of 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius).

While such major volcanic events are sporadic, Peterson said, pyroCb events occur every year. But scientists have not studied these storms enough to understand their potential impact on the climate.

Original article on Live Science.