Iridescent Algae Glow with Their Very Own Opals

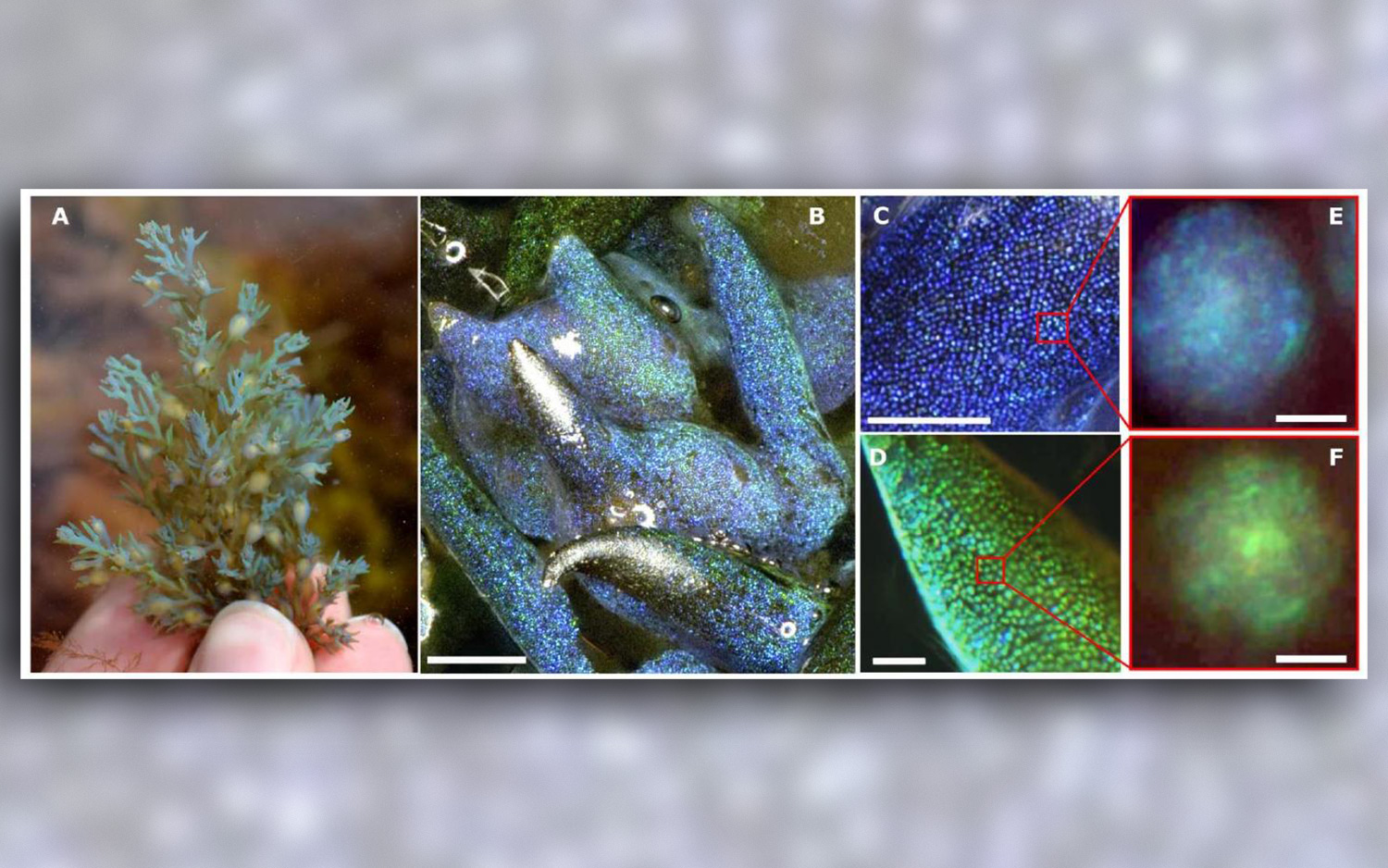

Algae can be glamorous, too: In the crisp, clear waters off the Atlantic coast in the United Kingdom, an unassuming, bushy seaweed glows in deep blues and greens. It turns out that this species is packed with opals — but, not the gemstone.

Rainbow wrack (Cystoseira tamariscifolia) is a type of brown alga found in the Mediterranean Sea and off the Atlantic coast of Europe. In the water, these algae glow. And although there are many glimmering organisms that live in the water — for example, bioluminescent jellyfish and lantern fish — most produce their own light.

Rainbow wrack, on the other hand, doesn't. Instead, just like the precious gemstone, it uses a crystal structure to reflect sunlight, according to a new study published April 11 in the journal Science Advances.

To study the shimmering seaweed, a group of researchers gathered the plant from a typical tourist-inhabited beach in southwest England during low tide. Using a variety of microscopy techniques, they discovered that the alga's cells contained baggies of "opals." [Gallery: Eye-Catching Bioluminescent Wonders]

Again, not the gemstone. Physicists use the term "opal" to describe any material with a very specific, tightly packed lattice structure, said senior study author Ruth Oulton, a physicist at the University of Bristol. Whereas gemstone opals are made from spheres of silicon dioxide, this algal opal is made from oil droplets called lipids. But all "opals" reflect light in very similar ways. (Opals are also found in insects: shiny beetles and some butterflies have hard opal structures on their exteriors.)

It's very rare for plants to have opal-like structures, but if they do, they're usually found in a hard exterior, like cellulose in cell walls, Oulton told Live Science. In the case of rainbow wrack, "it's the first time that an opal's been found that's not made of hard material inside a living thing."

What's more, the researchers found that rainbow wrack reacted to the light, changing its structure to dim and brighten itself, depending on the conditions. When there was ample light, the alga took apart its tightly packed opal structure to dim its glow. But when surrounded by near darkness, within a few hours it re-ordered all of the spheres back together into a lattice. Soon, it was glowing again.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers don't know exactly why rainbow wrack adopted this mechanism. But because this species lives in an area where changes in the tides sometimes leave it exposed on the beach and other times buried under 9 feet (3 meters) of water, they think it could have evolved to regulate the amount of light that reaches its chloroplasts — organelles that direct photosynthesis in cells. It's more than likely not a coincidence that the baggies of opals are surrounded by chloroplasts, Oulton said.

"What we know is seaweed itself can change [its] opal … when it gets lighter, the opal structure disappears," Oulton said. "When [a] beetle dies, the opal is still there, but if the seaweed were to die, all of it would disappear," she added.

Scientists can't yet replicate the process of turning the opals on and off in the lab, but they'd like to be able to. After talking to some chemists, the team figured out that this new finding could open up new possibilities, such as biodegradable displays. For example, if they can mimic rainbow wrack's process of packing and unpacking opal structures based on light, researchers may be able to create biodegradable packaging and labels from something as commonplace as coconut oil.

This could take the form of labels on food packaging that turn a different color, based on expiration dates; or plastic in packaging that totally disintegrates after a while, the researchers said.

In the meantime, rainbow wrack will continue to sway in high tides, looking glamorous as always.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.