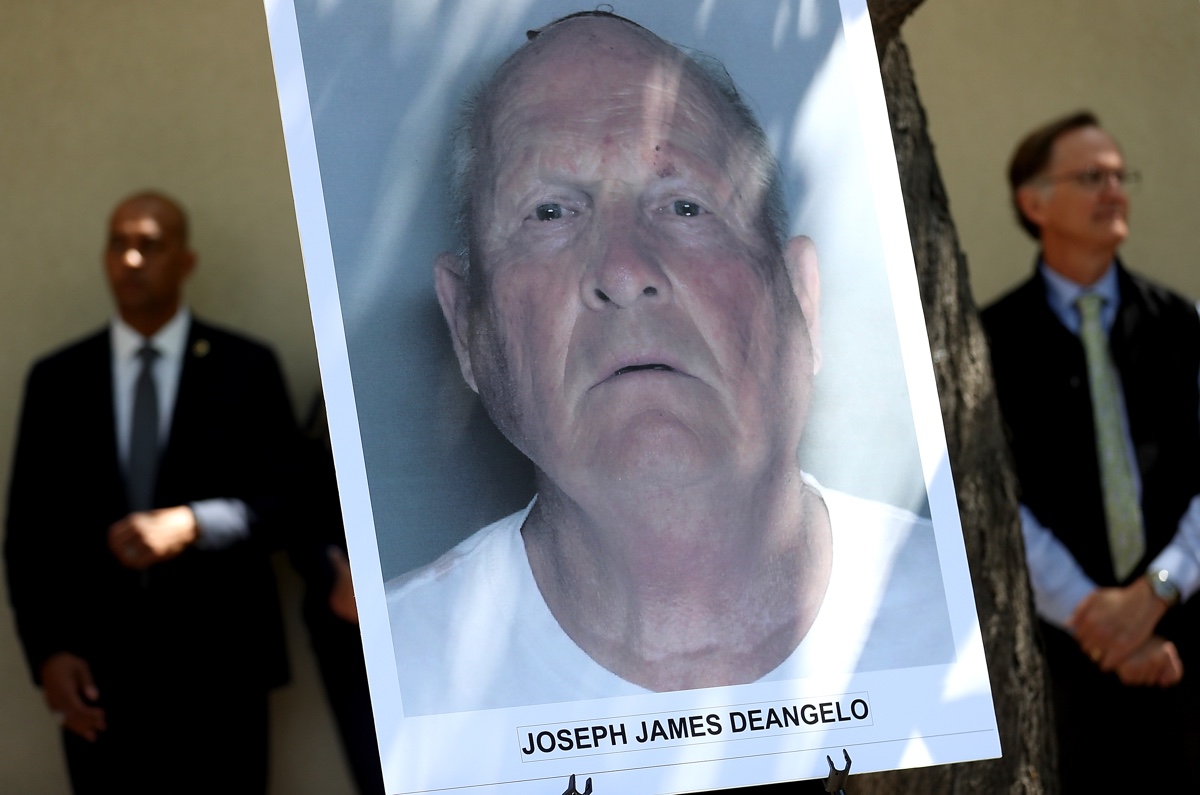

How the Golden State Killer's DNA Nabbed Him

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 12:51 p.m. E.T. on Friday, April 27.

DNA testing kits such as 23andMe can tell you all about your family's ancestry … but they can also potentially catch a serial killer.

The notorious "Golden State Killer," known for a series of rapes and murders in California in the 1970s and 1980s, evaded capture for decades, but his genes finally caught up to him. Armed with DNA that the killer left behind at various crime scenes, investigators used a shot-in-the-dark method to track him down: They painstakingly searched through numerous genetic profiles on popular genealogy websites to see if they could find DNA that matched that of the murderer — and they just about did, according to the Sacramento Bee. In fact, the investigators homed in on the genetic profile of someone who appeared to be related to the killer. The bulk of the search was done on GEDmatch, an open-source genealogy website that makes users' genetic information available for anyone to see without needing a court order, according to the San Jose Mercury News.

By the time police began intense surveillance on 72-year-old suspect Joseph James DeAngelo, they were strongly suspicious he was the killer, the Bee reported. They just needed stronger evidence than his relative's DNA. So, they waited for him to discard something holding his own DNA on it. [Unraveling the Human Genome: 6 Molecular Milestones].

Though law enforcement officials didn't reveal what objects they got DeAngelo's DNA from, they would've eventually gotten it from something or another. We discard our DNA everywhere: We leave behind dead skin cells on our keyboards, shed strands of hair or eyelashes, and leave bits of saliva on the rims of glasses. For forensic scientists, this "discarded DNA" is often the key to pinning a crime to a suspect.

Thanks to modern DNA techniques and interest, DeAngelo was arrested on Tuesday (April 24).

Genetic fingerprinting is the bar code of justice

Modern genetic fingerprinting techniques need only a small sample of DNA, even a discarded scrap of it, to read a person's unique genetic code, said Angelique Corthals, an assistant professor and forensic anthropologist at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. And at-home DNA testing kits work in a similar way to those techniques.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can actually get DNA from a 20,000-year-old individual, [so] surely we can get a full sequence from a person who shed their cells just a couple of days ago," Corthals told Live Science.

Over 99 percent of our DNA as humans is the same, but reading that remaining 1 percent allows forensics experts to pinpoint exactly who we are. Save for identical twins, each person has a unique genome. (Fun fact: Twins do have unique fingerprints.)

It's like scanning a bar code, Corthals said. "Based on the similarity of patterns between discarded DNA and the evidence that was collected at the time of the crime, you can basically, pretty much ensure that you have a match," she said. "And that pattern doesn't require you to sequence the entire genome of a person, so you can just target those areas which will be informative."

Why modern forensics can solve decades-old crimes

Since DNA sequencing came onto the scene, time is typically not a factor in catching a killer; officials usually sequence the DNA from a crime scene at the time of the crime or shortly thereafter. This way, they have the unique pattern ready to go when they need to compare it with a suspect's DNA, Corthals said. Sometimes, police even freeze the DNA for future use or freeze-dry it in a powder form; both methods allow them to keep DNA for, hypothetically, millions of years.

But the collection of DNA itself can be time-sensitive. Genetic material can be damaged with time if it isn't preserved properly; it can unravel or break under heat and chemicals, or get hidden in a tangle of contaminants. [7 Diseases You Can Learn About from a Genetic Test]

"Anything that's older than a couple of days will always be a lot more prone to contamination," Corthals said. That contamination can include genetic material from the people who handle the DNA or other animals that trample around it, or even chemical deposits. But "there are many techniques nowadays to sort out what is contamination," Corthals added. New technology called a lab-on-a-chip evades contamination by testing DNA samples right there at the crime scene.

Of course, this is all if the suspect hasn't wiped the scene of his or her traces. Although wiping all traces of DNA is difficult to do, an experienced person would know how to kill DNA, by wiping it with chemicals or by heating it up, Corthals said. "When you heat up sugar in a pan, you get caramel," Corthals said. Same with DNA — you get a "garbled mass of nothingness." This is why it's more difficult to extract DNA from burn victims, though it's not impossible.

So why did it take so long to find the alleged Golden State Killer? "You actually would be surprised how many cases of murders go unsolved — even murders that are from a potential serial killer," Corthals said. "If it's true that the perpetrator was a cop, he would have been well-versed with what forensics [professionals] do when they go into a crime scene, so he would've made sure a lot of evidence would've been wiped out from [the] scene itself."

But we know that investigators had samples of the killer's DNA from the crime scenes. So it's more likely that detectives simply didn't have a sample of the killer's DNA to compare the collected samples with, Corthals said. "You always need a comparison, [so] if you don't have the comparative material, you just have evidence lying in your locker," Corthals said. "Technology itself cannot solve what detective work does."

No matter how well-versed he was in forensics, it seems the alleged Golden State Killer didn't prepare for an age of genetic curiosity.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to include additional information on the DNA testing service that was used to identify a suspect in the Golden State Killer case.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.