No, a Woman Wasn't 'Eaten Alive' By Scabies. Here's What Likely Happened.

An elderly woman in a Georgia nursing home died after reportedly being "eaten alive" by scabies, a skin disease caused by parasitic mites. But can these mites really kill a person?

Experts say that while the mites themselves don't directly lead to death, they can set the stage for serious, and potentially fatal, bacterial infections.

The 93-year-old woman, Rebecca Zeni, died in 2015 at the Shepherd Hills Nursing Home in LaFayette, Georgia, according to local news outlet WXIA-TV. An autopsy report lists the cause of death as "septicemia due to crusted scabies," WXIA-TV reported. A number of news outlets, including WXIA-TV, reported that Zeni was "essentially eaten alive" by the mites.

However, Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said that such headlines were hyperbolic. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

"It's not that the scabies mites themselves are killing" a person, Adalja said. Rather, these mites cause a disruption of the skin — a major barrier that protects your body from infectious microorganisms. With the skin compromised, "all the bacteria that live on the skin have a much easier road to get into your bloodstream," Adalja told Live Science.

This can lead to a bacterial infection in the bloodstream, which can cause potentially life-threatening complications, including an overwhelming immune response known as sepsis.

Adalja likened a patient with severe scabies to a burn victim, who is also vulnerable to bacterial infection due to skin injury.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Deaths tied to scabies are rare, but Adalja said it is "not surprising" that a scabies infection could lead to fatal complications in some patients, including the elderly — who may be at greater risk for scabies than younger people because they have a weaker immune system.

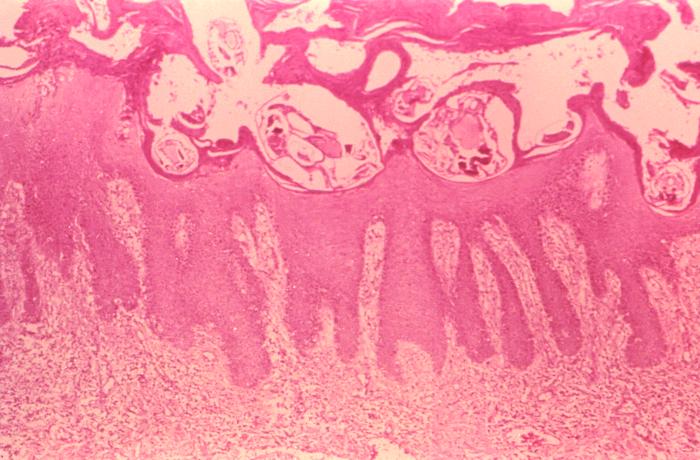

In people with scabies, the microscopic mites, known as Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, burrow into the upper layer of the skin and lay eggs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The condition causes a rash and intense itching. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies that can occur in those with weakened immune systems. These patients have thick crusts of skin that contain a large number — sometimes millions — of mites.

Scabies is contagious, and usually spreads through prolonged contact with the skin of someone with scabies. The disease can spread rapidly in crowded environments such as nursing homes, the CDC says.

When a person with scabies scratches, the individual can transfer bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, into the skin, which leads to the development of infections on the skin's surface, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Such superficial infections can, in turn, develop into deeper skin infections, as well as sepsis, if not treated.

Most people with scabies can be cured with prescription lotions or creams, which kill the mites. However, crusted scabies often requires stronger medicine such as ivermectin — an anti-parasitic medication, according to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). Many patients with crusted scabies need more than one dose of the treatment to cure the disease, the AAD says.

Zeni’s family has filed a lawsuit against PruittHealth, which operates Shepherd Hills Nursing Home, WXIA-TV reported.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.