Editor's Note: This story was updated at 5:10 p.m. E.T.

There's nothing like staring up at the night sky to make you feel small.

But when looking out into the cosmos, you might also wonder: What is the most massive known object in the universe?

In some ways, the question depends on what is meant by the word "object." Astronomers have spotted structures like the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall — a colossal filament of gas, dust and dark matter containing billions of galaxies that stretches for about 10 billion light-years in length — which could contend for the title of biggest object ever. But classifying this assembly as a unique object is problematic because it's hard to figure out exactly where it begins and ends.

"Object" actually has a clear definition in physics or astrophysics, said Scott Chapman, an astrophysicist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. "That's something bound together by its own self-gravity," he said, such as a planet, star or the stars orbiting within a single galaxy.

With this in mind, it's a bit easier to figure out what's in the running for the most massive thing in the universe. The award could go to different entities depending on the scale being considered, but each prizewinner has provided scientists insights into the limits of size and mass in the cosmos. [Big Bang to Civilization: 10 Amazing Origin Events]

Biggest planet, star and galaxy cluster

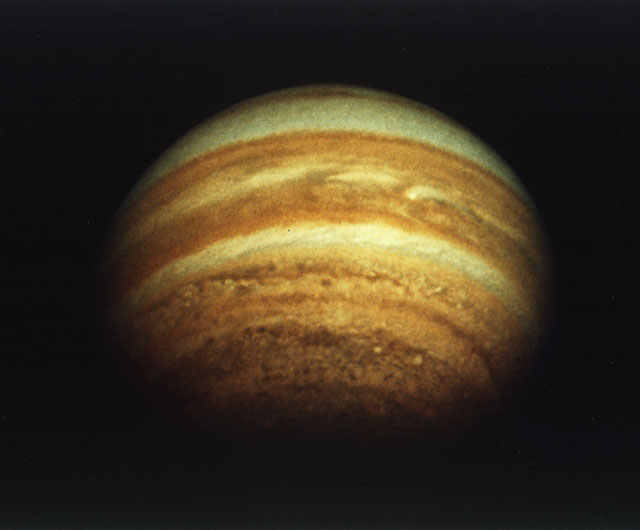

For our relatively tiny species, the planet Earth is plenty big, at about 13 septillion lbs. (6 septillion kilograms) — or 13 with 24 zeroes after it. But it's not even the largest planet in the solar system, being dwarfed by the outer giants Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and mighty Jupiter, which weighs in at 4.2 octillion lbs. (1.9 octillion kg), or 4.2 with 27 zeroes after it. Researchers have uncovered thousands of planets orbiting other stars, including many that make our local giants look puny. Discovered in 2016, HR2562 b is the heaviest exoplanet found to date, with a mass 30 times that of Jupiter. At that size, astronomers are unsure whether to classify the behemoth as a brown dwarf, which would make it a type of small star rather than a planet. [By Jove! 7 Weird Facts About Jupiter]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

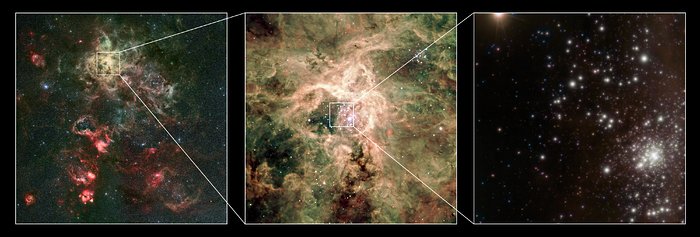

Stars themselves can grow to enormous sizes, with the most massive known star, R136a1, being somewhere between 265 and 315 times heavier than our sun, which is a mind-boggling 4.4 nonillion lbs. (2 nonillion kg), or 4.4 with 30 zeroes after it. Located 130,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a companion galaxy orbiting our Milky Way, R136a1 is so big and bright that the light it emits is actually tearing it apart, according to a 2010 study in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The electromagnetic radiation streaming from the star is powerful enough to carry away material from the surface, causing the star to lose about 16 Earth's worth of mass every single year. Astronomers are unsure exactly how such a self-destructive star could form and how much longer it will hold itself together.

Galaxies are the next objects up the size scale of the cosmos. The Milky Way galaxy is already mind-bendingly massive, stretching 100,000 light-years from end to end, containing approximately 200 billion stars, and weighing about 1.7 trillion times the mass of our sun. But it can't compete with the central galaxy of the Phoenix Cluster, a leviathan 2.2 million light-years across that contains about 3 trillion stars, according to NASA. At the center of this beast is a supermassive black hole — the largest ever seen — with an estimated mass of 20 billion suns. The Phoenix Cluster itself is an enormous accumulation of approximately 1,000 galaxies all orbiting one another about 5.7 billion light-years away with a total mass of about 2 quadrillion suns, which is 2 with 15 zeros after it, according to a 2012 paper in the journal Nature.

But even that goliath can't compete with what is likely the most massive object ever seen — a recently discovered galactic protocluster known as SPT2349, which was described April 25 in the journal Nature.

"We hit the jackpot with this structure," Chapman, whose team uncovered the record-breaker, told Live Science. "More than 14 very massive individual galaxies crammed into the space of something not much larger than our Milky Way."

Spotted when the universe was just a tenth of its current age, the individual galaxies in this pileup will eventually combine into one gargantuan galaxy, the most massive in the universe. And it's just the tip of the iceberg, Chapman said. Further observations have revealed that the total structure contains around 50 additional galaxies that will all settle into an object known as a galactic cluster, in which many galaxies all orbit one another. The previous most massive record-holder, the appropriately named El Gordo Cluster, weighs the equivalent of 3 quadrillion (or 3 with 15 zeroes after it) suns, but SPT2349 is likely to outweigh it by at least four to five times.

That such an enormous object could form when the universe was just 1.4 billion years old was surprising to the researchers, since computer simulations suggested it would normally take much longer for such large objects to appear.

"The central massive galaxy forms incredibly early and much more explosively and rapidly than we would have imagined," Chapman said. "Just the blink of the eye on the cosmic timescales."

Given that humans have searched only a fraction of the sky for such things, even more massive objects might be lurking out there in the universe, he added.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the name of the massive galaxy pileup that is the biggest known object. It is SPT2349, not the Dusty Red Core.

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.