Meet Kim, the First Spider to Jump on Demand

A tiny but proficient jumper named Kim is the first spider ever trained by scientists to leap on demand.

Teaching her to jump when and where they wanted her to wasn't easy. Of the four spiders the researchers tried to train, only one — which they eventually nicknamed Kim — would obligingly hop between parallel platforms and leap to higher or lower levels. By studying Kim, the scientists hoped to better understand how jumping spiders fine-tuned their jumps, depending on the purpose of the leap, the distance of their target and the jump's direction — upward or downward. [Creepy, Crawly & Incredible: Photos of Spiders

After observing and measuring Kim's performance, the scientists described their findings in the most detailed study of spider jumps to date, published online May 8 in the journal Nature: Scientific Reports.

The regal jumping spider (Phidippus regius), which measures only 0.5 inches (12 millimeters) long, is part of a group that is well-known for using swift, long-distance jumps to catch fast-moving insect prey or navigate tricky terrain and avoid threats. And while most jumping spiders measure between 0.1 and 0.4 inches (3 to 10 mm), they are capable of leaping horizontally up to 6 inches (160 mm) from a standstill.

"The force on the legs at take-off can be up to five times the weight of the spider. This is amazing," lead study author Mostafa Nabawy, a researcher at The University of Manchester's School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, said in the statement.

"If we can understand these biomechanics, we can apply them to other areas of research," Nabawy said.

Might as well jump

Previous studies examined spiders' jump speed and body position, but much about their jumping was still unknown, such as how they adjusted their posture to compensate for different conditions, the amount of energy that powered their jumps and how much their jumps relied on muscular force, rather than hydraulic pressure that sends blood rushing to their legs, the study authors reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To investigate the spiders, they built a structure with two movable platforms that could be fixed at different levels and distances, and then tried to train four female P. regius spiders to jump between the platforms, by carrying them back and forth to familiarize them with the apparatus.

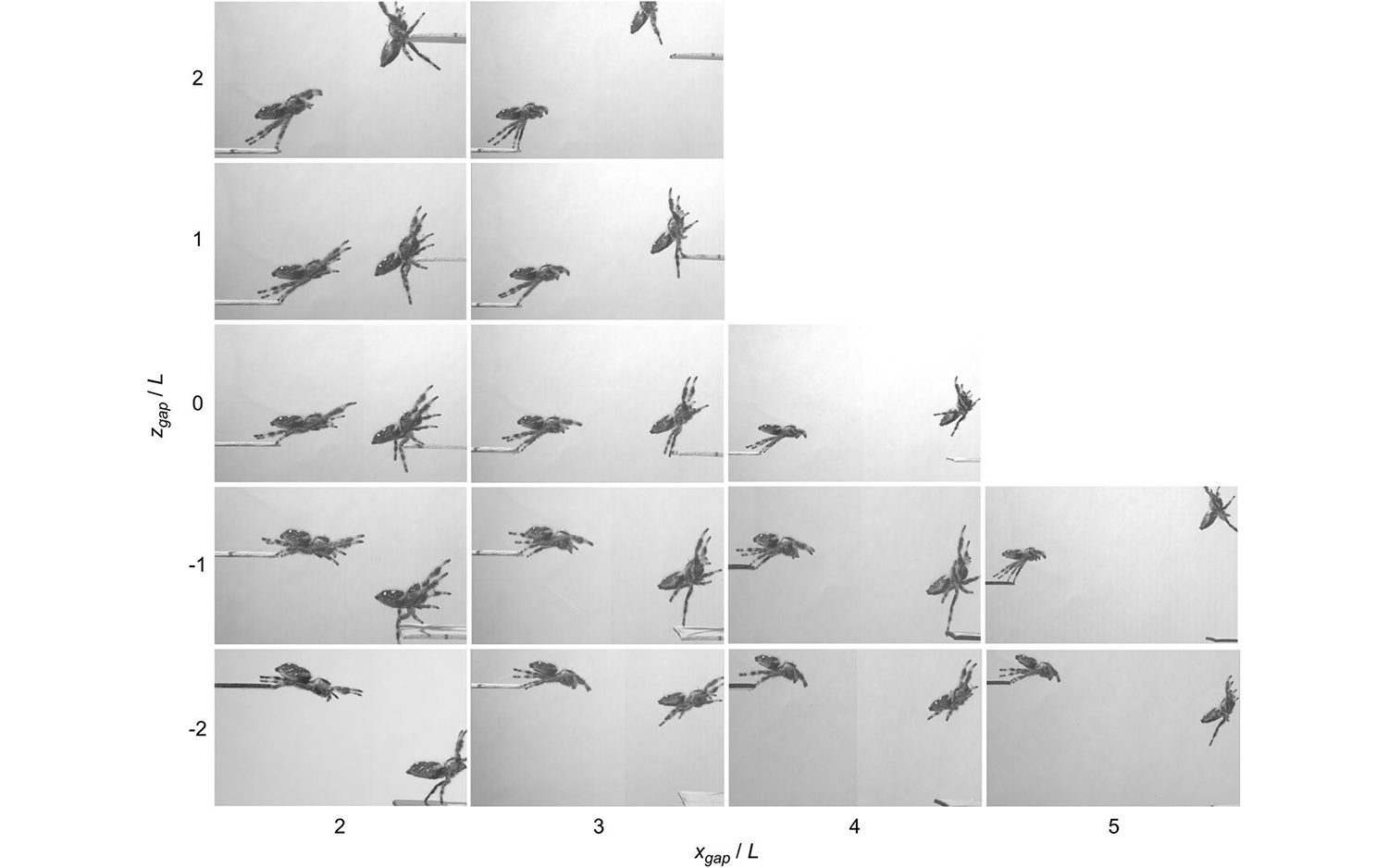

Most of the spiders showed no interest in the experiment. Kim, however, jumped at the opportunity, becoming the scientists' lone source of data. She performed in 15 jumping tasks, leaping up, down and across the platforms, while the researchers filmed her with high-speed cameras. They recorded her speed, landing positions, leg and body angles, and lengths of the jumps, and then calculated how much energy Kim spent on every leap.

They also scanned and modeled Kim in 3D, to better visualize the structures and movements of her legs and body.

The researchers found that Kim deployed different strategies depending on where she had to jump. She adjusted the position of her legs depending on the distance of the targets, and she used lower-angled jumps to travel shorter distances, and steeper jumps for longer distances.

The short-range horizontal jumps tended to be lower and faster, requiring Kim to expend more energy but minimizing the amount of time she was in the air — and likely increasing her chances of catching prey. By comparison, long-distance horizontal hops or jumps to a higher or lower platform required her to use less energy, according to the study.

Spiders' leg movements are known to employ both muscles and hydraulic pressure — mechanisms in their bodies send blood swiftly flowing to their limbs when they extend their legs. But the scientists noted that there was enough force generated by Kim's leg muscles alone to fuel her leaps, without requiring her to rely on hydraulic pressure to propel swift takeoffs.

However, further research would be necessary to confirm whether the spiders do, in fact, push off solely with muscular power, the scientists reported.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.