What Can Human Mothers (and Everyone Else) Learn from Animal Moms?

Mother's Day celebrates the accomplishments of human mothers, but how do moms across the animal kingdom cope with the demands of pregnancy, birth and child rearing?

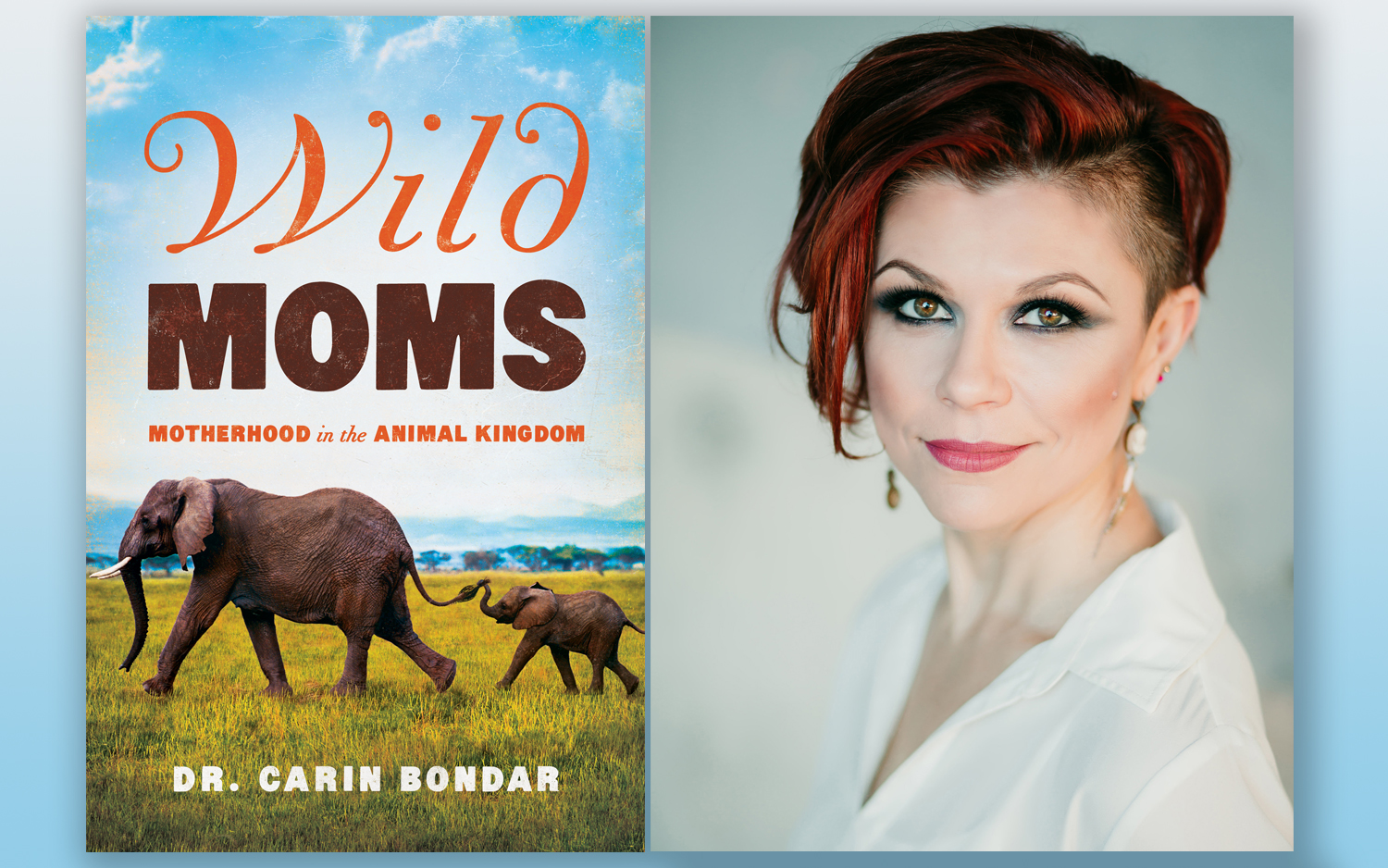

In "Wild Moms" (Pegasus Books, 2018), author, biologist and mother Carin Bondar investigates motherhood in the natural world, sharing the strategies used by numerous species to bear and nurture their offspring.

The challenges of motherhood in the wild are daunting — everyday survival concerns such as avoiding predators and finding food are amplified when a female has a little one (or several) to protect and nourish. In some social animals, such as lions or gorillas, new threats can even emerge from the animal's own community, as dominant males often kill infants sired by other males, when they take over a group.

And some obstacles are unique to individual species. In humans, our comparatively narrow pelvises are excellent for upright walking, but they aren't the best fit for our babies' large skulls, making birth more difficult and dangerous than it is for our closest living primate relatives. Meerkat females that hope to reproduce must first prove themselves as the dominant female in their group, or forfeit raising their own young to help the "queen" with her litters.

Many animal mothers also face the tough decision of having to choose between their offspring, nurturing one and neglecting another, so that the fittest — and the mother herself — will have a better chance at survival.

In her book, Bondar takes on these and other fascinating aspects of motherhood — from dolphin moms teaching newborns how to swim (and breathe); to lion "communes" where groups of mothers nurse each others' cubs; to mourning practices among chimpanzees for deceased infants. Bondar recently spoke to Live Science about the vast diversity of mothering approaches in the animal kingdom, revealing many surprising parallels to the practices of human mamas.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science: Being a mother is hard work — more so for some than for others. What are some of the harsh realities of animal motherhood that might make human mothers think, "I don't have it so bad after all?"

Carin Bondar: Just based on the length of gestation, an elephant is a good example. They're pregnant for nearly two years, so by the time they actually give birth, they've already lent their bodies to this offspring for a lengthy period. And if that offspring dies — which often will happen in the animal kingdom — that's such a significant investment that's just gone. [For How Long Are Animals Pregnant? (Infographic)]

For birthing, humans do have it pretty bad, but not as bad as the poor hyena, which has to give birth through her pseudopenis. This is basically a long tube — picture a foot-long hot dog, and you have the idea. She has to give birth to two cubs through that, and for first-time moms the rate of death is significant — it's something like 30 percent — and the asphyxiation rate for cubs is extremely high. For decades, it's been one of the great mysteries of hyena biology — why would they evolve this structure that make birthing so difficult and so dangerous? But the social benefits to having this pseudopenis are thought to be more important than the cost of giving birth.

For the early phase of mothering, all primate moms have it pretty difficult, and that's because primate moms have babies that are so needy — ours are among the neediest — but they're also very complicated. Apes have personalities to consider as well as basic survival behaviors, and primate moms often have a very steep learning curve when it's their first time.

This is very similar to human moms — at least, to me. I was in a state of shock for many months after I had my first child; I had no idea what to do! I was kind of comforted to learn that other primates have this very steep learning curve as well, it's not like you get it right your first time, like, for example, a duck mom. The babies hatch and she just goes, "Hey, follow me over here!" They have the genetic mechanisms in place to parent, and they know what they're doing. It's not like that for monkeys and apes.

Live Science: In your book, you mention a disturbing drawback to the steep learning curve for primates — some first-time macaque mothers demonstrate physically abusive behavior toward their young. What could explain why a monkey would hurt her baby?

Bondar: Scientists are becoming bolder in their assertions that animal emotions play a role; it's an emerging area of science. Animals are subject to many of the same processes and basic neurobiology of emotion as we are — love, connection and also depression and the dark side of emotions. There's depression in many monkeys and apes, associated with changing levels of certain neurotransmitters and many of the same hormonal factors that are associated with depression in humans.

When we're taking about brains that are as complicated as the ones that monkeys and apes have, there's room for things to misfire. We're learning how to quantify these things, especially with populations that are very well studied, and that's why we know about things like infant abuse in macaques, because there are these huge populations that are relatively free-living that we have been studying for many decades. And so we're able to get a much greater and more comprehensive look at what happens in a population behaviorally.

Live Science: What about animal mothers that don't involve themselves in raising their young at all — such as cuckoos, who leave their eggs in other birds' nests. Isn't that taking a big risk, abandoning your baby to a possibly hostile stranger?

Bondar: It's so jarring when you first learn about these animal moms that lay eggs not only in another mom's nest, but in the nest of a completely different species. And they never come back, then never check in — it's basically just lay your eggs and go. This is called brood parasitism and it's a really successful strategy. And what's interesting is that we do see emotional attachment in birds, so it's fascinating that this other strategy has evolved to counteract that completely — but that's why I love biology!

For birds, the eggs need to be incubated, and then nestlings need food — there's a lot of care required for baby birds, and cuckoos are able to avoid all of that. And that's pretty significant, because what it means is that they can simply put more effort into laying more eggs immediately — they get ahead by simply saving their energy to lay more. And for birds that have this strategy, their overall populations on a global scale are increasing, because as more climates open up to them, they can find more species to parasitize — and they're good to go.

Live Science: Motherhood can mean having to make tough choices. What kind of hard choices do wild animal moms sometimes have to face?

Bondar: This question makes me think of seals and sea lions. A lot of the aquatic mammal moms have this massive investment to make, especially those who live in northern climates. Their babies need a ton of fat to be able to stay warm, and it's also very dangerous, so there's huge investment on the part of these moms.

Often what we see is a strategy that sounds utterly heartless. If there's a "toddler" that's still breast feeding, an aquatic mammal mom will almost always hedge her bets by having another calf. But if there aren't enough resources to go around, the calf has to be starved to death — basically, the toddler will push the newborn off the boob, and the mom lets it happen. In the long run it's worth it, as far as genes and the future generations are concerned. But I'll never believe that it's not emotionally devastating for any mom.

Live Science: In our closest primate relatives, how are birth and motherhood integrated into the social fabric of animals' lives?

Bondar: Humans have diverged in this really strange direction — we have our own houses, and we take our babies into them, and we try to stick it out, and be strong, and pretend that everything's great. Other apes don't do that. Other ape mothers are playing the role of midwives, helping with the delivery, taking the baby immediately and allowing the mom to rest. That's not to say it's all lovey-dovey — it isn't. But there's more of a sense of community around the initial bonding process, within the direct social group. That aspect of parenting seems to be something that humans are kind of cheating ourselves on, perhaps because we've internalized it and we've made it into a competition.

Live Science: When you were writing this book, was there any point where you came across a mothering strategy for an animal and thought to yourself, as a mother, "I have to try that!" or "I wish I could do that!"

Bondar: I'm a mother of four, and I had postpartum depression all four times — it was crappy! I've since learned that there are actually some fairly significant lines of evidence suggesting that ingestion of the afterbirth can guard against postpartum depression. We don't understand the mechanics of it, but it's thought that there's some aspect of the neurochemicals, steroids and hormones in the afterbirth, that safeguard moms against a lot of things.

Humans are unique in that we're one of the few species that does not consume the afterbirth — apes, monkeys and mammals do. And that's something that humans seem to be missing, maybe it's because we've thought about it a little too much and we've decided that it's gross. But there's actually a lot of biological evidence that suggests that we're getting it wrong. Had I the opportunity to do it all over again — which I'm happy that I don't! — I'd probably take more charge of my own birthing processes.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.