Lab-Grown Human-Chicken Hybrid Embryos Are No 'Frankenfowl'

Scientists recently combined human stem cells with chicken embryos, but that doesn't mean the researchers are breeding flocks of "frankenfowl."

Rather, the scientists are looking closely at how those embryonic cells organize themselves, to better understand how embryos develop and how cells build specialized body structures.

Experiments that graft cells onto a growing embryo date to nearly 100 years ago, and in 1924, such experiments in amphibians led scientists to discover "the organizer," a region of embryonic cells that manipulates the development of other cells. But an organizer in primate embryonic cells (humans included) has been elusive — until now. A new study describes the first evidence of a human organizer, marking, according to the researchers, a significant breakthrough in the study of developmental biology. [3 Human Chimeras That Already Exist]

Because of ethical limitations attached to working with human embryos, experiments looking for human organizers could be done only with stem cells, which are then grafted to embryos belonging to other animals such as chickens, the scientists wrote in the study.

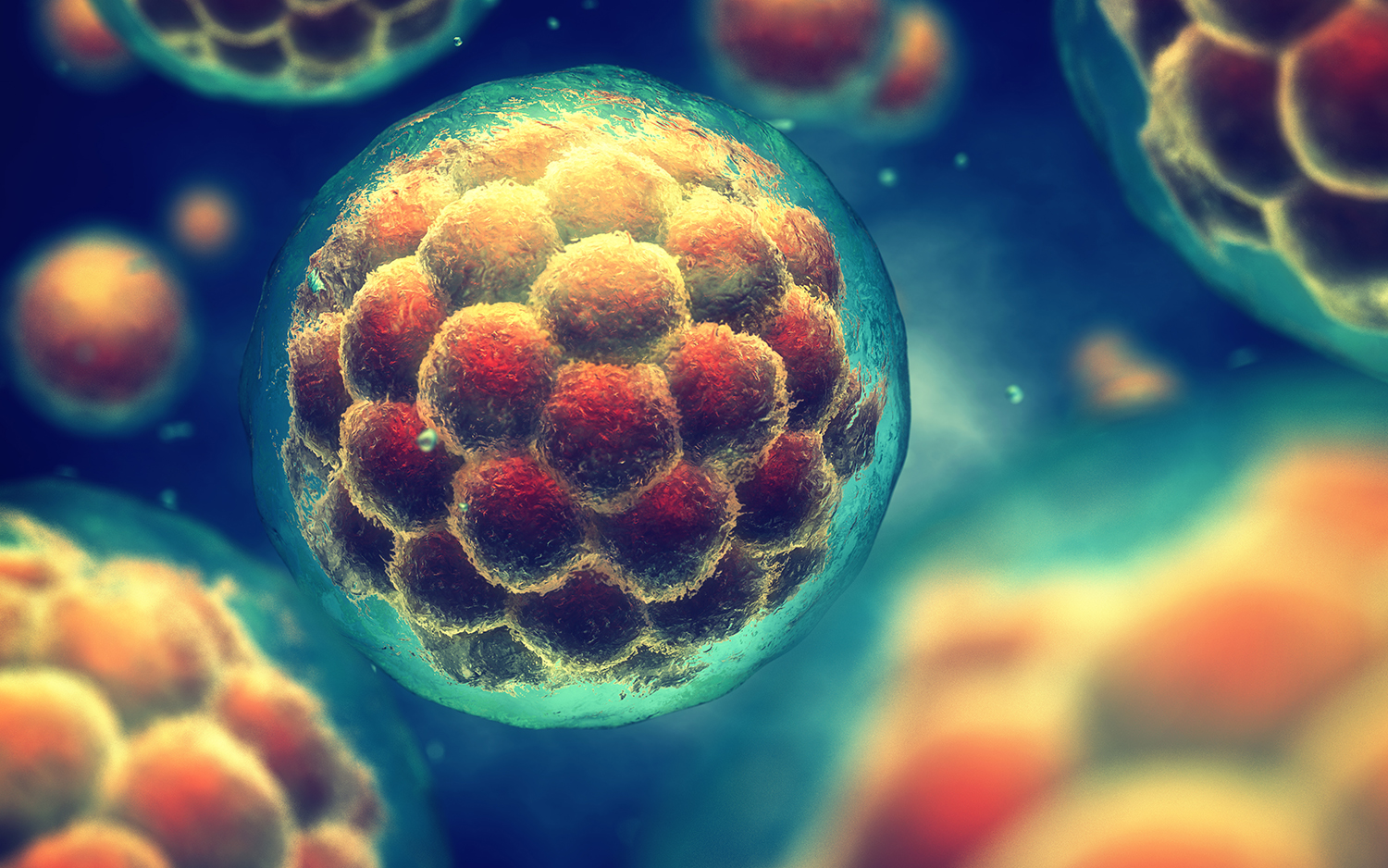

Combining human stem cells with animal embryos creates animal models known as chimeras, which contain cells from both the host and the cell donor. These chimeras therefore have two sets of DNA. Since 2016, scientists have integrated human stem cells into pig and sheep embryos as part of an investigation into the possibility of growing human organs in those animals. And in 2017, experiments produced the first viable pig embryos that incorporated human cells, Live Science previously reported.

Finding the organizer

For the new study, researchers used special disks to cultivate early stage human stem cells and then introduced growth-stimulating proteins. The scientists found that after they added these proteins, called Wnt and Activin, the stem cells began forming tissue that produced proteins typically found in organizers. This was the first time that organizer-like cells had been grown from human stem cells, the study authors wrote.

But the real test lay in what would happen after the researchers grafted this cluster of cells to a developing embryo. When they introduced these stem cell colonies into chicken embryos, the human cells survived and mingled with the host cells, according to the study. Then something amazing happened — the human cells assembled into a type of tissue that eventually forms a backbone, and the cells also began instructing the chicken embryo cells to turn into tissue for a nervous system.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Generating a human organizer "closes the loop" that pioneering embryologists initiated almost a century earlier, the researchers wrote in the study. The finding hints that the role of an organizer in embryonic cell development has been retained along evolutionary pathways that span the vertebrate tree of life, "from frogs to humans," the scientists said.

The success of the human-chicken chimeras also presents new possibilities for future research exploring early development in human embryos, the researchers concluded.

The findings were published online May 23 in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.