Ötzi the Iceman Was a Heart Attack Waiting to Happen

This story was updated May 30 at 12:02 p.m. EDT.

If a modern heart doctor could give medical advice to the iceman Ötzi — the man who was preserved as a mummy after his murder about 5,300 years ago in the snowy Alps — it would be this: Stop eating so much fatty meat and consider taking medications that lower your blood pressure and cholesterol.

This advice is based on a new comprehensive look at the iceman mummy's cardiovascular health. A full-body computed tomography (CT) scan showed that Ötzi had three calcifications (hardened plaques) in his heart region, putting him at increased risk for a heart attack. [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Otzi the Iceman]

Ötzi also had calcifications around his carotid artery, which carries blood to the head and neck, and in the arteries at the base of his skull, which carry blood to the brain. Both hardened plaques likely elevated Ötzi's risk of a stroke, said Dr. Seth Martin, a preventive cardiologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore who wasn't involved with the new study.

Granted, because Ötzi didn't have access to modern medicines during his lifetime, such as cholesterol-lowering statins, "we'd be focusing on a plant-based, vegetarian diet," Martin told Live Science. "Folks who follow a more plant-based or Mediterranean diet — that's the type of diet that can help prevent heart disease."

It's too bad Ötzi likely had a taste for meat. In an earlier study, researchers found that Ötzi's last meal included the fatty meat of a wild goat, as well as wild deer and grains.

If Ötzi's condition were bad enough (and if he had a time machine that could transport him to modern times), doctors might give him a carotid endarterectomy, a surgery that involves opening or cleaning the carotid artery to help prevent stroke, Martin said. Ötzi could also undergo coronary bypass surgery, a procedure that diverts blood flow around the blocked artery, Martin noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

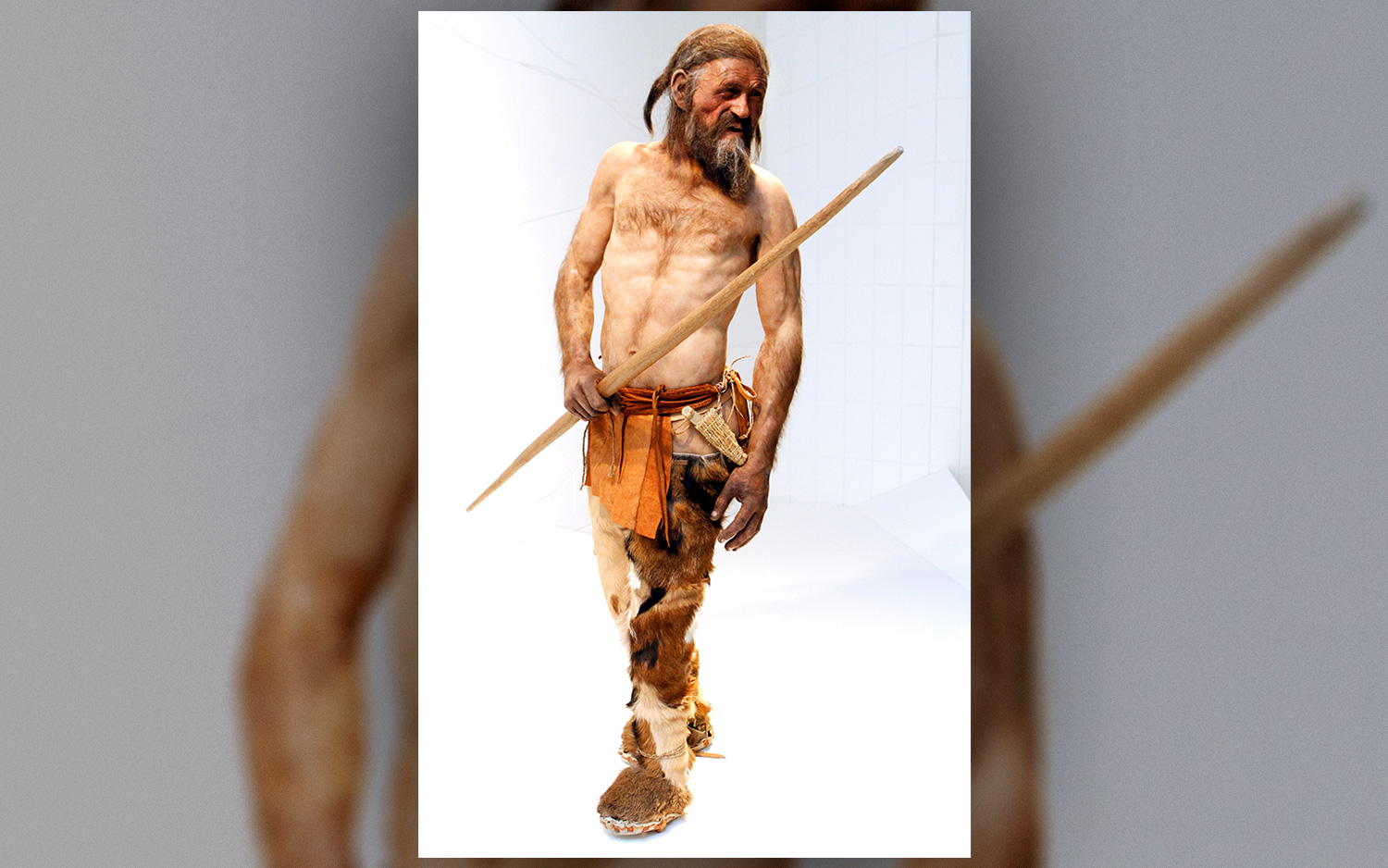

Ötzi's health

Ötzi may be old, but he was found fairly recently. Hikers found him buried in the Italian Alps in 1991, and he is now housed at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. The iceman is one of the most studied mummies in the world: Researchers now know that he had bad teeth and knees; lactose intolerance; a probable case of Lyme disease; stomach bacteria that causes ulcers; and 61 tattoos inked on his body, Live Science previously reported.

Now, the new study suggests that if Ötzi hadn't been killed by a blow to the head and an arrow that pierced his shoulder when he was about 46 years old, he might have faced health problems from these plaques down the road.

An earlier study in the journal Global Heart found that Ötzi had a genetic predisposition for atherosclerosis, a narrowing of the arteries from fatty deposits, Live Science previously reported. What's more, CT scans done at the time showed signs of generalized atherosclerotic disease in in some of his arteries, including the carotid arteries, the distal aorta and the right iliac artery, the earlier study found. However, it was not known before that Ötzi also had calcifications in his heart, which indicates a more advanced atherosclerosis with an increased risk of stroke or heart attack, said Albert Zink, the head of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Academy, who was not involved with the new study.

Given that Ötzi wasn't overweight, didn't smoke tobacco, regularly exercised and likely didn't have a high-fat diet (at least by today's standards), it appears that his genes — and not his daily routine — explained his health condition.

"I suspect that lifestyle didn't play a major role in his development of plaque," Dr. Philip Green, an interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science. Despite the suggestion that Ötzi go vegetarian, Zink sees it another way. "Compared to modern standards, he would not be considered as a risk patient," Zink told Live Science. "So, I think a different diet, such as vegetarian or vegan, wouldn’t have helped Ötzi." [9 New Ways to Keep Your Heart Healthy]

In the new study, the researchers examined a newer CT scan of Ötzi that was done in 2013. This was Ötzi's first, complete head-to-toe CT scan; his two arms poked out at odd angles, so Ötzi didn't fit in a regular CT machine. Thanks to a new, larger CT scanner at the Central Hospital in Bozen-Bolzano, the researchers were able to image Ötzi's entire body, including his abdomen and chest, allowing them to pinpoint the hardened plaques.

There is no doubt Ötzi is one of the oldest cases of vascular calcification, and "a medical example showing that a genetic predisposition is probably the most important trigger factor for arteriosclerosis and coronary heart disease," study co-researcher Patrizia Pernter, a radiologist at Bozen-Bolzano, said in a statement.

The study was published online May 28 in the German and Austrian journal Advances in the Field of X-Rays (RöFo – Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Röntgenstrahlen).

Editor's Note: This story was updated to include additional information about Otzi's medical history.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.