How Did Easter Island Statues Get Their Massive 'Hats'?

Archaeologists put on their thinking caps to solve a long-standing puzzle about another kind of cap: the enormous stone "hats" that sit atop the heads of colossal statues on Easter Island, a place also known as Rapa Nui.

The solemn, carved faces of the imposing rocky figures, or moai, are a dramatic sight, towering up to 33 feet (10 meters) high and weighing as much as 82 tons (74 metric tons). Many of the statues are topped by red stone cylinders called pukao, carved separately from the statues and made of a different type of rock.

And researchers finally have answers about how those hefty toppers were transported and lifted into place, reporting the findings May 31 in the Journal of Archaeological Science. [Photos of Walking Easter Island Statues]

Rapa Nui, located in the Pacific Ocean about 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) east of Chile, was first populated by people around 800 years ago. Over time, these people crafted about 1,000 giant statues, which they may have moved into position by "walking" them upright along roads, rocking them from side to side with ropes to travel long distances across the volcanic island.

Prior studies suggested that pukoa represented a type of hairstyle worn by the Rapa Nui people. But it was unclear if pukao were placed on top of the statues before the moai were moved into place or afterward, and experts were also uncertain about exactly how the large headpieces were maneuvered onto the giant heads, the researchers wrote.

Rock and roll

In the new study, the scientists photographed and digitally modeled 50 pukao — some on statues and some abandoned on the ground — and 13 unfinished cylinders from the pukao quarry on Rapa Nui. They then looked for structural similarities that might offer clues about how the giant stones were prepared, moved and installed.

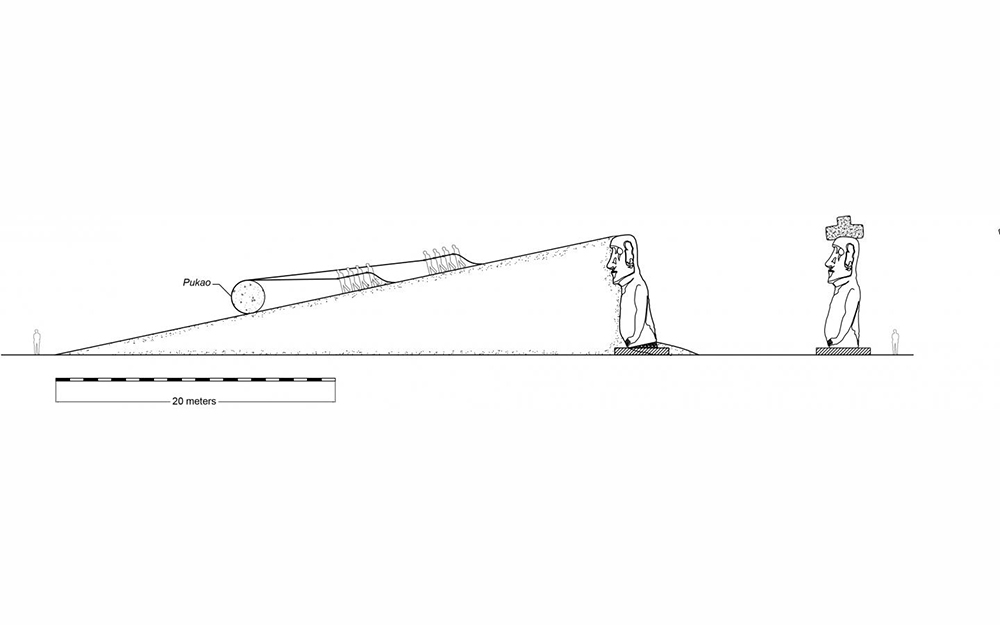

Sizable pukao weighed as much as 13 tons (12 metric tons) and measured as big as 6.5 feet (2 m) in diameter, the researchers reported. Pukao found scattered around the island were bigger than the ones perched on statues; this told the scientists that the cylinders were likely rolled unfinished to sites where statues already stood. Chips of the distinctive red stone found near statue-mounted pukao hinted that they were carved into their final shapes on those sites, the scientists wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To install pukao, workers used dirt to build ramps at the front of forward-leaning statues. People at the top of a ramp would have hoisted the hat up to a statue's head using a process called parbuckling, often used to right capsized ships, the study suggested. First, the workers would have attached a single long rope to the steepest part of the incline, wrapped the ends around the stone and pulled the ends to drag the cylinder up. Even the biggest pukao could have been moved this way by 15 or fewer workers; the technique would have stabilized the stone and kept it from rolling back down, according to the study.

Previous research noted that construction of the statues on Rapa Nui led to widespread deforestation, with trees sacrificed as building materials or to clear land for roads or agriculture to feed the imagined thousands of workers that must have been required for the statues' construction, the study authors reported.

However, the new findings about the ingenuity and efficiency of the Rapa Nui people paint a different picture. This research suggests that the enigmatic builders maintained a more sustainable relationship with their island ecosystem "and used their resources wisely to maximize their achievements and provide long-term stability," study co-author Carl Lipo, a professor of anthropology at Binghamton University, said in a statement.

"These were quite sophisticated people who were well-tuned to the requirements of living on this island," Lipo said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.