'Lost' NASA Tapes Show Humans Sort of Caused Global Warming on the Moon Too

There is a decades-old mystery at NASA: Why did the moon's temperature suddenly rise nearly 4 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) right after the first astronauts planted their flags there? When scientists first encountered this puzzle in the early 1970s, they knew that lunar dust — or regolith — could give astronauts a fever; was it possible that astronauts were giving the moon a fever right back?

Seiichi Nagihara, a planetary scientist at Texas Tech University, suspected that the key to explaining this mysterious lunar heat wave lurked in temperature readings recorded by Apollo astronauts between 1971 and 1977. The only problem was that hundreds of the reels of magnetic tape holding those records went missing nearly 40 years ago, thanks to an archival blunder.

Now, after a grueling eight-year search, Nagihara and his colleagues have tracked down and restored more than 400 reels of those lost NASA tapes. In a new study published April 25 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the researchers used these tapes to propose a logical (if slightly embarrassing) hypothesis to explain the temperature increase: The astronauts, later nicknamed the "dusty dozen," may have been way too dusty for their own good. [5 Mad Myths About the Moon]

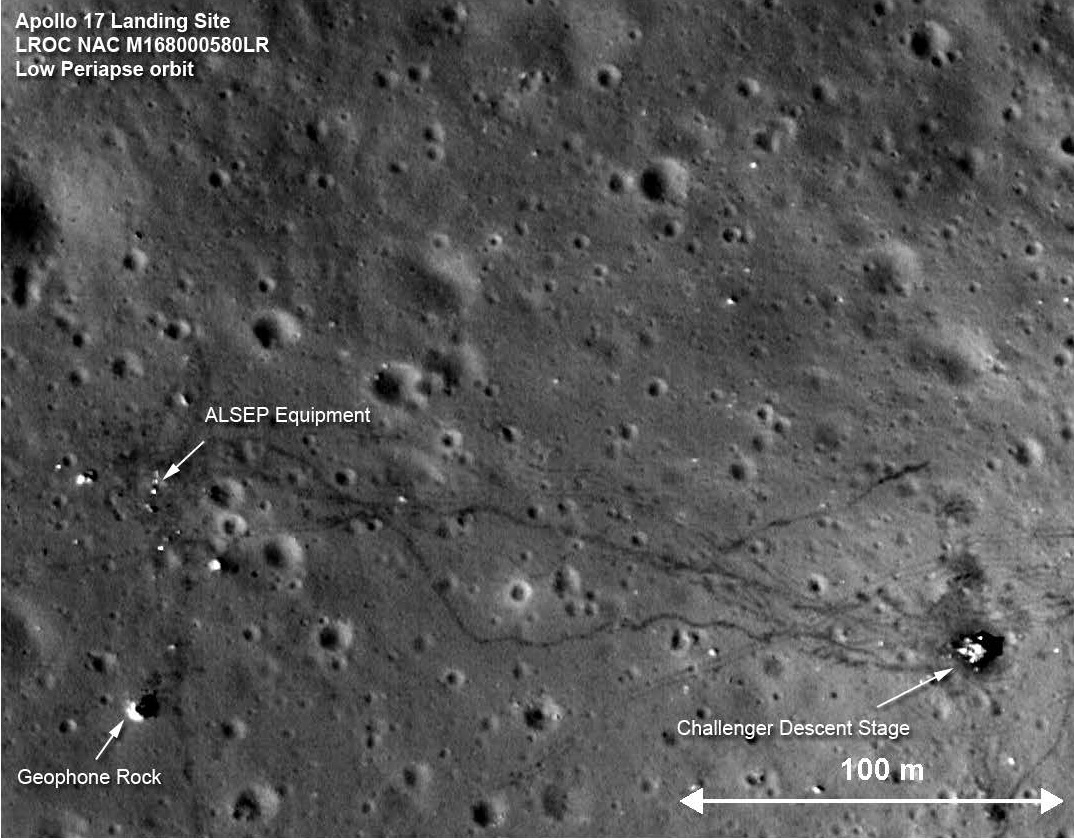

"You can actually see the astronauts' tracks, where they walked," study co-author Walter Kiefer, a senior staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston told the CBC. "And we can see … where they scuffed dirt up — and what it leaves behind is a darker path."

According to the new study, the 12 Apollo astronauts who walked on the moon between 1969 and 1972 kicked aside so much dust that they revealed huge regions of darker, more heat-absorbing soil that may not have seen the light of day in billions of years. Over just six years, this newly exposed soil absorbed enough solar radiation to raise the temperature of the entire moon's surface by up to 3.6 degrees F (2 degrees C), the study found.

"In other words," Kiefer said, "the astronauts walking on the moon changed the structure of the regolith."

Finding the lost Apollo tapes

Astronauts first planted temperature probes on the moon's surface during the Apollo 15 and 17 missions, in 1971 and 1972. While these probes transmitted data steadily back to the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston until 1977, only the first three years of recordings were ever archived with the National Space Science Data Center.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For their new study, Kiefer, Nagihara and their colleagues embarked on a quest to find the missing tapes. The researchers tracked down 440 of these tapes at the Washington National Records Center in Suitland, Maryland; unfortunately, that trove of data represented only about three months of temperature records taken in 1975.

To augment the newly recovered records, the team pulled hundreds of weekly performance logs from the Lunar and Planetary Institute. The logs included temperature readings taken from the Apollo probes between 1973 and 1977, meaning the researchers could fill in some of the gaps left by the other missing tapes.

Climate change on the moon

After several years of extracting and analyzing data from the archaic tape reels, the researchers discovered that probes planted near the moon's surface recorded a greater and faster temperature jump than the probes planted deeper down found. This indicated that the temperature spike was beginning at the surface and not within the moon itself, the researchers said.

A quick study of lunar surface photos taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera provided another crucial clue. The photos showed that areas near the Apollo landing sites were crisscrossed with dark streaks where the astronauts had walked or driven about the moon's surface, apparently kicking a lot of ancient dust aside.

In fact, the researchers said, the mere act of installing the temperature probes may have thrown off those probes' measurements by altering the surface environment around the instruments — and significantly increasing the surface's temperature.

"In the process of installing the instruments, you may actually end up disturbing the surface thermal environment of the place where you want to make some measurements," Nagihara told the American Geophysical Union. "That kind of consideration certainly goes in to the designing of the next generation of instruments that will be someday deployed on the moon."

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.