Don't Stare into a Laser Pointer Beam. You Could Burn a Hole in Your Eye.

Laser pointers may jazz up your PowerPoint presentation, but they can pose serious hazards to your eyes if you use them the wrong way. Case in point: A boy in Greece burned a hole in his retina after repeatedly staring into a laser-pointer beam, according to a new report.

The 9-year-old boy's parents brought him to the eye doctor because he was having vision problems in his left eye, according to the report, published yesterday (June 20) in The New England Journal of Medicine.

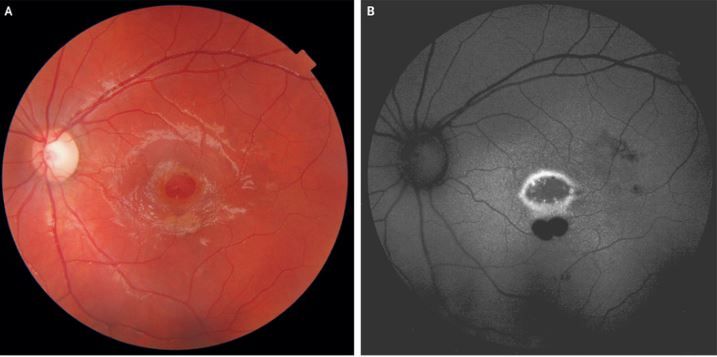

An eye exam revealed a large hole in the boy's macula, a part of the eye's retina that's responsible for central vision, or the ability to see things straight in front of you, according to the National Eye Institute.

The boy "reported playing with a green laser pointer and repeatedly gazing into the laser beam," the report said. ['Eye' Can't Look: 9 Eyeball Injuries That Will Make You Squirm]

Health officials have warned for years about the possible dangers of laser pointers for people's eyes. The energy from a laser pointer aimed into the eye "can be more damaging than staring directly into the sun," according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The FDA restricts the sale of laser pointers to a maximum power of 5 milliwatts. However, laser pointers may not have the proper labeling, or they may have a higher power than indicated on the label, making it difficult for consumers to know exactly how powerful a laser pointer is, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. In addition, people can buy more powerful laser pointers over the internet, according to the report. It's unclear how powerful the laser pointer in the Greek boy's case was.

An eye test revealed the boy's vision to be 20/20 (normal) in his right eye but 20/100 in his left eye, the report said. A person with 20/100 vision needs to be 20 feet away from a reading chart to see letters that a person with normal vision can see at 100 feet, according to the American Optometric Association.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The damage to the boy's eye was too severe for him to benefit from surgery, according to the report. A year and a half after the boy's doctor visit, his vision remained about the same, the report said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.