These Skeletons from an Ancient Egypt Cemetery Were Riddled with Cancer

Archaeologists have uncovered six cases of cancer while studying the bodies of ancient Egyptians who were buried long ago in the Dakhleh Oasis. The finds include a toddler with leukemia, a mummified man in his 50s with rectal cancer and individuals with cancer possibly caused by human papillomavirus (HPV).

The researchers found these cancer cases while examining the remains of 1,087 ancient Egyptians buried between 3,000 and 1,500 years ago.

Extrapolating from these cases, the researchers estimated that the lifetime cancer risk in the ancient Dakhleh Oasis was about 5 in 1,000, compared with 50 percent in modern Western societies, wrote El Molto and Dr. Peter Sheldrick in a paper published in a special cancer issue of the International Journal of Paleopathology. "Thus, the lifetime cancer risk in today's Western societies is 100 times greater than in ancient Dakhleh," they wrote. [Photos: Ancient Egyptian Cemetery with 1 Million Mummies]

Molto, a retired anthropology professor at Western University in Ontario, Canada, cautioned that some people living at Dakhleh could have died of cancer without any traces being left in their remains and that people in the ancient world tended to have shorter life spans than people today. However, even accounting for these factors, the researchers believe the risk of cancer was considerably lower in ancient Egypt.

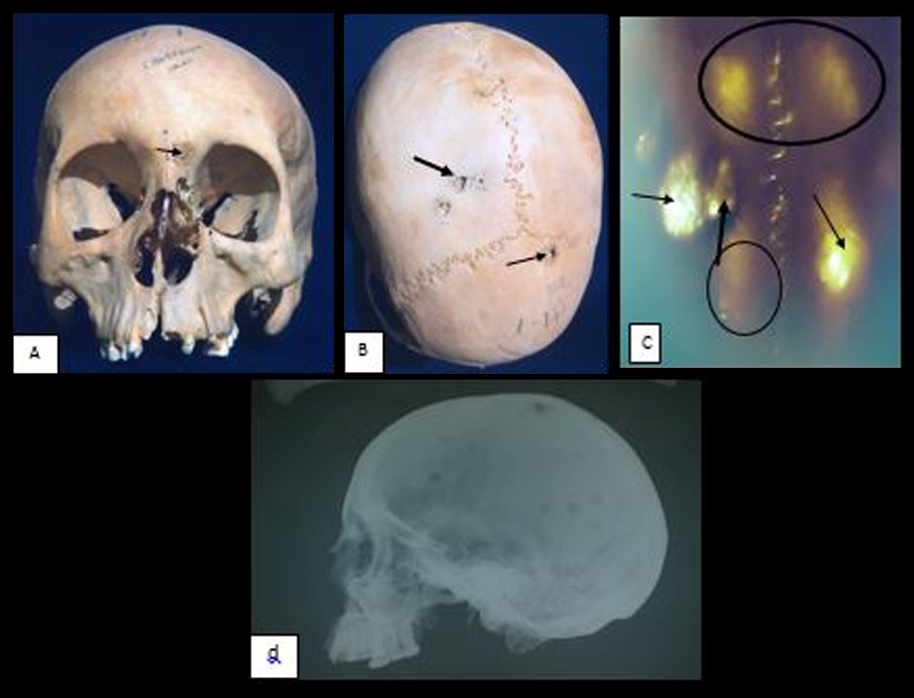

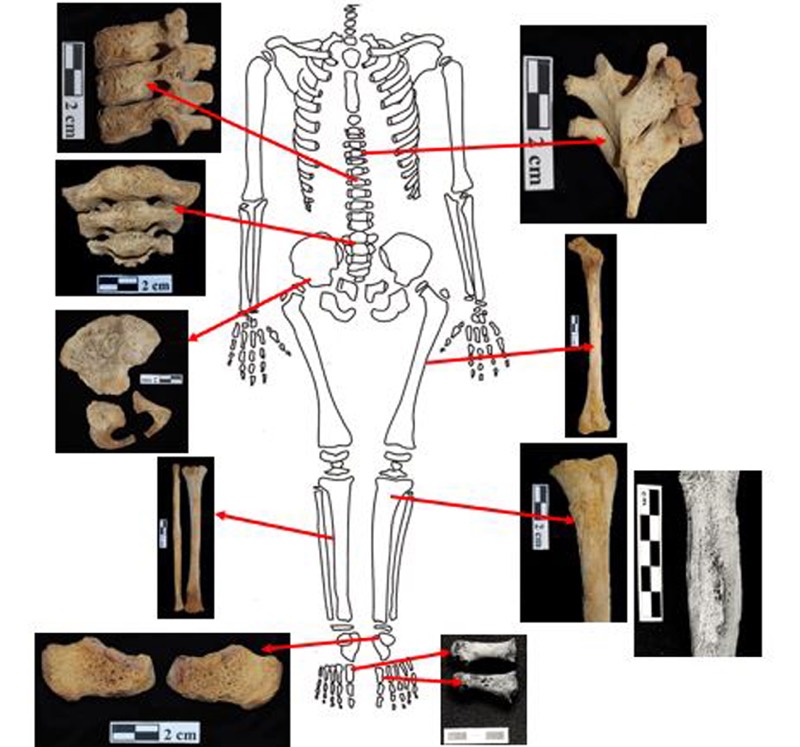

In five of the six cases, scientists determined that they had cancer by studying lesions (holes and bone damage) on their skeletons. Those holes were left when cancer spread throughout their bodies. For instance, a woman in her 40s or 50s had a hole on her right hip bone that is about 2.4 inches (6.2 cm) in size that researchers believe was caused by a tumor. In one case (the man in his 50s with rectal cancer), an actual tumor was preserved. Researchers cannot be certain where the cancers originated in many of the cases.

Young adults

Three of the six cases (two females and one male) were people in their 20s or 30s, an age when it is rare for people to get cancer, the researchers said.

"When the Dakhleh cases were first presented at professional meetings, a common comment against accepting the diagnosis of cancer was that 'their ages were too young,'" wrote Molto and Sheldrick, a physician in Chatham, Ontario, in their paper, referring to the three young adults. [Image Gallery: Digging Up a Cemetery in Dakhleh Oasis]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, recent research has revealed that HPV is a major cause of several forms of cancer, including those that often affect young adults. "HPV is a confirmed cause of cancer of the uterine cervix and testes, and it evolved in Africa long before Homo sapiens emerged," wrote Molto and Sheldrick in their paper.

"The two female and the male burials from Dakhleh, all young adults, could have, respectively, developed cancer of the uterine cervix and testicular cancer," the authors wrote. "We know from current cancer epidemiology research that both types of cancers peak in the young adult cohorts."

While scientists were not able to genetically test the three young adults to see if they had HPV, other studies confirm that it did exist in the ancient world, Molto and Sheldrick wrote, noting that the virus likely existed in the ancient Dakhleh Oasis.

No ancient treatments

So far, research into Egyptian medical texts and human remains have revealed no indication that the ancient Egyptians had a specific treatment for cancer.

"They knew that something nasty was going on," Molto told Live Science. However, "we have no indication as to specific treatments for cancer, because they didn't understand [what cancer was]," Molto said, adding that the ancient Egyptians may have tried to treat some of the symptoms such as skin ulcers.

The researchers said they hope that in the future, data will be gathered on cancer and other diseases in the modern-day Dakhleh Oasis. This data could then be compared to the ancient rate to provide more clues as to how the risk of cancer has changed over time.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.