Future Astronauts Must Perform Surgery in Space — and It Will Be Gross

There's already enough to worry about when planning a one-way trip to Mars. Did you pack enough sunblock to deflect the deadly cosmic radiation? Will there be enough water there? What if your assigned procreation partner doesn't like you? Now, scientists writing in the British Journal of Surgery have provided one more thing to fear: floating blobs of infectious bodily fluids.

According to the authors of a new paper published last week (June 19), runaway blood, urine and fecal matter are just some of myriad possible complications of space surgery that likely await future astronauts. In a review of studies called simply "Surgery in space," the team of researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and King's College Hospital in London scoured six decades of scientific literature to compile the most comprehensive (and fascinating) list of those complications yet. [7 Everyday Things That Happen Strangely in Space]

"Future astronauts or colonists will inevitably encounter a range of common pathologies during long‐haul space travel," the authors wrote in the new review. "Novel pathologies may [also] arise from prolonged weightlessness, exposure to cosmic radiation, and trauma."

And right now, at least, humans are woefully unprepared to deal with it.

Surgery in space

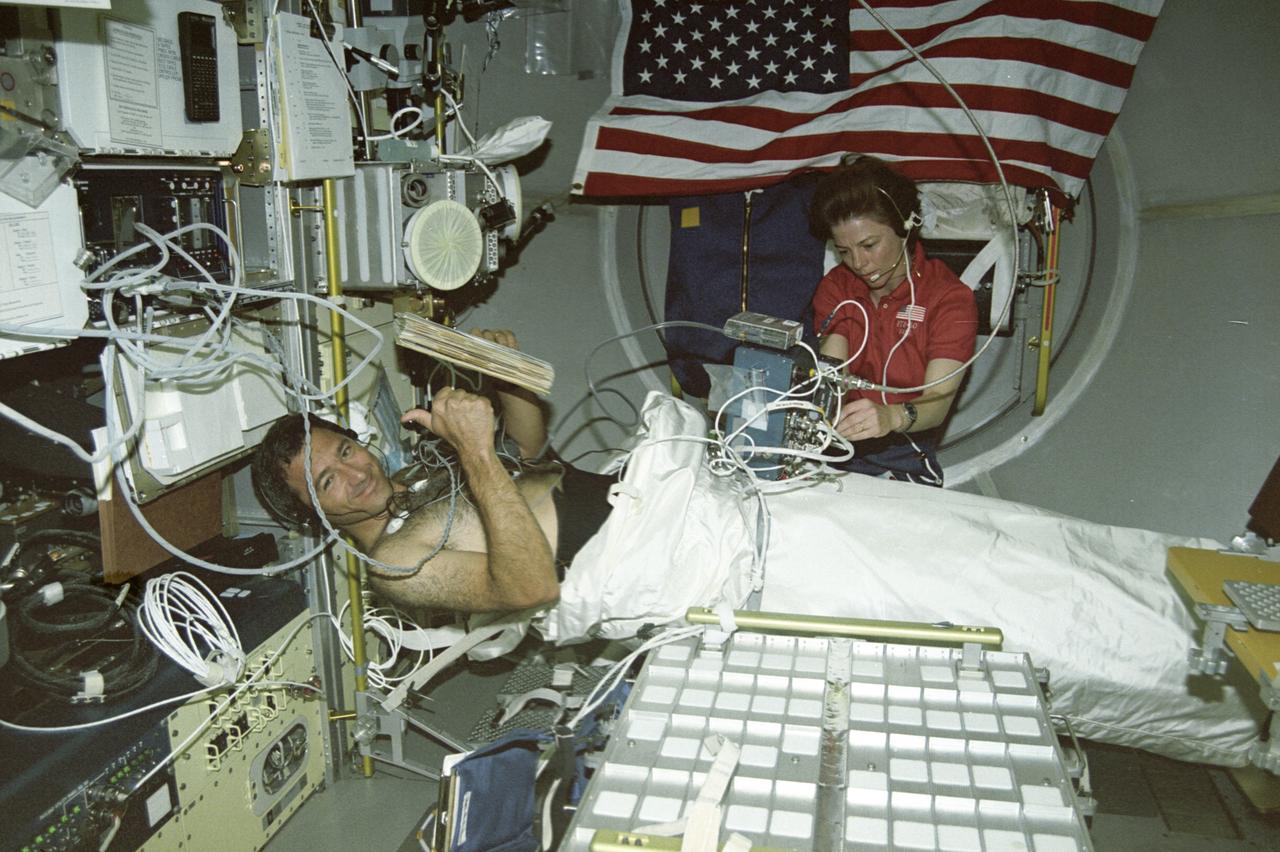

There's a lot in space that can hurt an astronaut but not a lot of good ways to deal with those hazards. Currently, the go-to method for treating medical emergencies aboard the International Space Station involves returning astronauts to Earth as soon as possible, the authors of the review wrote.

On Mars — which currently takes about 9 months to reach under favorable conditions — running home will not be an option. And having a doctor on Earth perform surgery remotely with the help of medical robots is equally unfeasible.

"The distance between Earth and Mars is 48,600,000 miles [78,200,000 kilometers], meaning a communication delay of anywhere between 4 and 22 minutes for radio signals," they wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If surgery in space is necessary, then, it will have to be performed in person by highly trained humans. This poses problems of its own. For starters, storage space on existing spacecraft is scarce enough as it is, without having to accommodate a small hospital.

"It would be impossible to carry all the equipment necessary to treat every anticipated space [condition]," the authors wrote.

One way around this, previous studies have suggested, is 3D printing. Instead of launching ships into the void carrying every medical tool known to humanity, send them aloft with a digital database of 3D-printable templates for every medical tool known to humanity. This way, astronaut doctors could print only the precise tools they needed, when they needed them.

A floating bowel

The surgery itself will be another challenge. To combat microgravity aboard the ship, patients will have to be physically restrained, the authors wrote. Once the patient is secured, wrangling the bodily fluids that are leaking from that patient's open wounds will be another, messier challenge.

"Because of the surface tension of blood, it tends to pool and form domes that can fragment on disruption by instruments," the authors wrote. "These fragments may float off the surface and disperse throughout the cabin, potentially creating a biohazard."

Worse still: Without gravity holding the patients' bowels in place, they may float up and rest against the patients' abdominal walls while the patients are restrained, the authors wrote. This increases the risk that the patients' bowels would be accidentally "eviscerated" during surgery — leaking gastrointestinal bacteria into the patient's body and the ship at large.

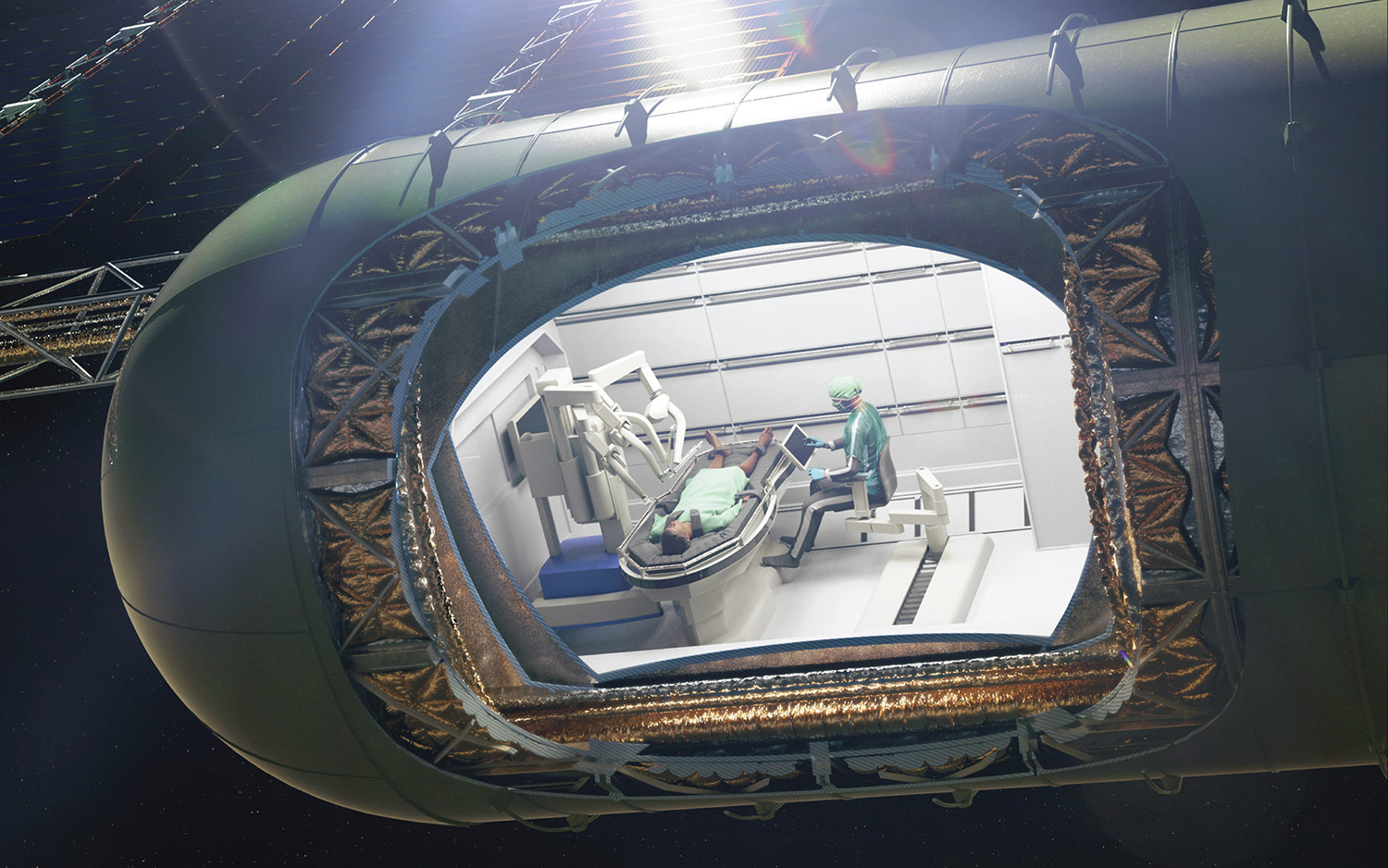

One proposal for avoiding contamination by blood and … whatever else … to cover the patient in a "hermetically sealed enclosure" separate from the rest of the ship. This could take the form of a specialty "traumapod," the researchers wrote, which would be a small, sealed medical module built into future spacecraft.

Humans have a way to go before any of these novel problems are under control, but the world's space agencies are working hard on solutions. NASA has been experimenting with telemedicine in an underwater laboratory designed to simulate a space environment, the authors wrote, and several labs have been investigating stem-cell-based drugs that could help astronauts automatically regenerate their bones and other tissues in microgravity.

With enough innovation, space — the final frontier of medicine — can be conquered, one ruptured bowel at a time.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.