No Aliens, But Scientists Find More Evidence for Life on a Saturn Moon

Large, carbon-rich organic molecules seem to be spewing from cracks on the surface of Saturn's icy moon, Enceladus, according to a new study of data collected by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. The discovery means that Enceladus is the only place besides Earth known to satisfy all the requirements for life as we know it, space scientist and study co-author Christopher Glein said in a statement from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio.

So do aliens live there? It's definitely possible, but probably not what you're imagining.

"We cannot decide whether the origin of this complex material is biotic or not, but there is astrobiological potential," Nozair Khawaja, a planetary scientist at the University of Heidelberg in Germany and lead author on the study, told Gizmodo. What he means is that scientists are unsure of the source of these heavy molecules, but it could be from a living organism. [Cassini's Greatest Hits: Best Photos of Saturn and Its Moons]

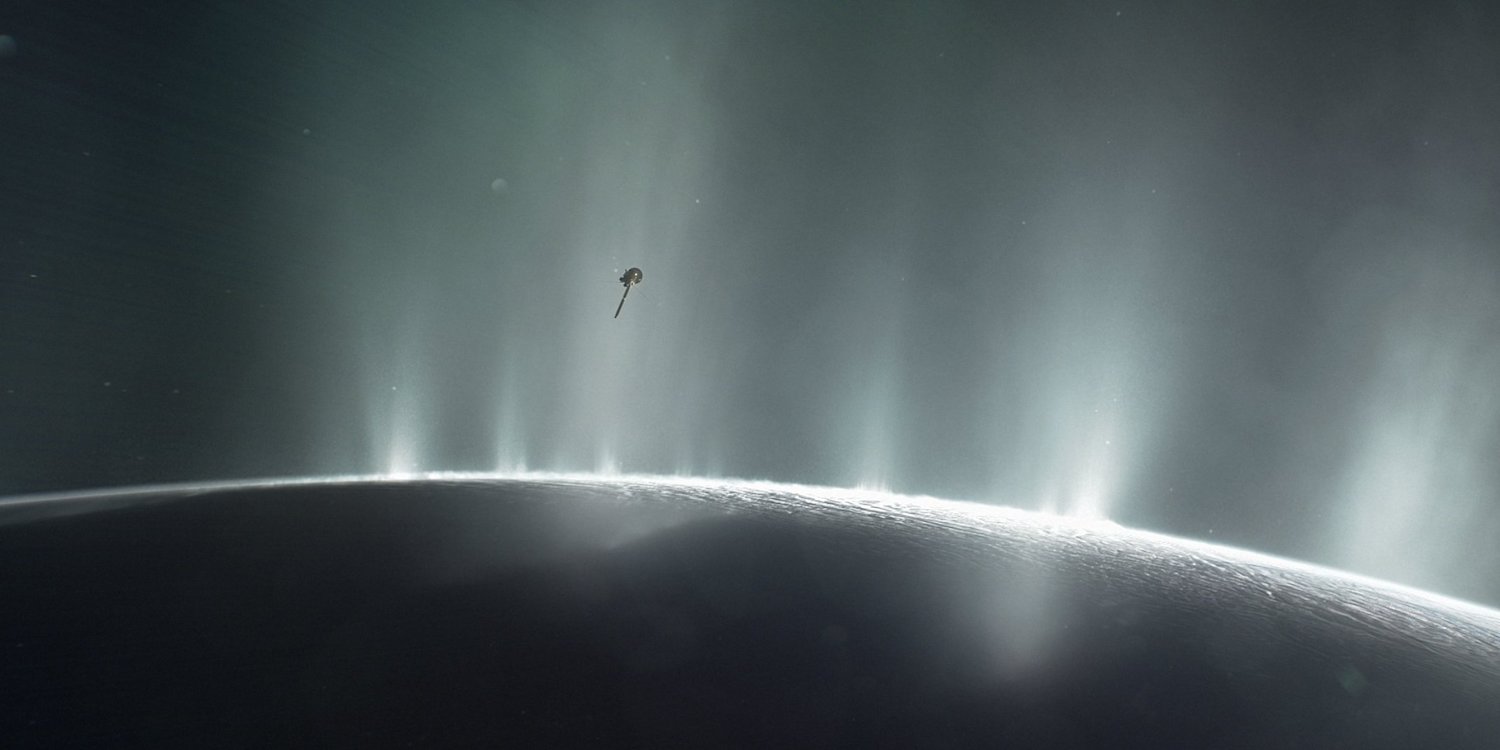

Beneath its icy crust, Enceladus holds a warm, mysterious ocean that sits above a rocky core. Enormous plumes of icy vapor hundreds of miles high escape from the subsurface ocean into space through cracks in the crust. Instruments aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft grabbed samples from those plumes during the craft's close flyby of Enceladus on Oct. 28, 2015. Cassini analyzed the samples using the Cosmic Dust Analyzer and a mass spectrometer. Researchers then reviewed the data and found the telltale signs of large, complex, carbon-rich molecules.

Until now, Cassini had detected only much smaller organic molecules with molecular masses less than 50 atomic mass units. These newly discovered molecules have molecular masses over 200 atomic mass units and are classified as macromolecules. And they're complex: They're made up of large chains and rings of carbon. "This is the first evidence of large organic molecules from an extraterrestrial aquatic world. They can be generated only by equally complex chemical processes," planetologist and study director Frank Postberg, of the University of Heidelberg, explained in a statement released by the university.

These types of molecules also don't dissolve in water, which means "gas bubbles probably transport the molecules to the surface, where they form an organic film," Khawaja said in the Heidelberg statement. "From there, it is launched into space together with ocean water droplets."

Cassini has also detected molecular hydrogen in the plumes emerging from Enceladus' surface — a key ingredient for life as we know it. "Hydrogen provides a source of chemical energy supporting microbes that live in the Earth's oceans near hydrothermal vents," Hunter Waite, an atmospheric scientist and principal investigator of the study, said in the statement from SwRI. With that in mind, the researchers wonder if these complex organic molecules could be coming from hydrothermal vents like the ones on Earth's seafloor, which are home to hundreds of primitive life-forms such as tube worms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Whether or not the source of these complex molecules is biological remains unclear, so the researchers look forward to the next generation of exploration to help them figure that out. "A future spacecraft could fly through the plume and analyze those complex organic molecules using a high-resolution mass spectrometer to help us determine how they were made," Glein said. "We must be cautious, but it is exciting to ponder that this finding indicates that the biological synthesis of organic molecules on Enceladus is possible."

The study was published June 27 in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Kimberly has a bachelor's degree in marine biology from Texas A&M University, a master's degree in biology from Southeastern Louisiana University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is a former reference editor for Live Science and Space.com. Her work has appeared in Inside Science, News from Science, the San Jose Mercury and others. Her favorite stories include those about animals and obscurities. A Texas native, Kim now lives in a California redwood forest.