Famed British Geologist Was Spectacularly Wrong About Stonehenge

In 1923, famed British geologist Herbert Henry Thomas published a seminal study on Stonehenge, claiming to have found the precise spots where prehistoric people had quarried the stones.

There was just one problem with his analysis: It was wrong. And it has taken geologists about 80 years to get it right, a new study finds.

"At best, he [Thomas] was forgetful and sloppy, but at worst he was being deceptive," said study co-researcher Rob Ixer, a geologist at the University of Leicester and an honorary senior research associate at the Institute of Archaeology at University College London, in England. [Stonehenge Photos: Investigating How the Mysterious Structure Was Built]

In addition to debunking Thomas' influential work, the researchers announced an additional Stonehenge discovery: Prehistoric people likely didn't boat the stones though Bristol Channel on the way from where the stones were quarried, in western Wales, to where Stonehenge stands today, in Salisbury Plain.

Rather, ancient people probably used a so-called inland superhighway, although this finding has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, said Ixer and study co-researcher Richard Bevins, a geologist at the National Museum Wales. Such a monumental procession would have been akin to transporting the space shuttle Endeavor in a parade, for all to see and celebrate, the archaeologists said.

Thomas' work

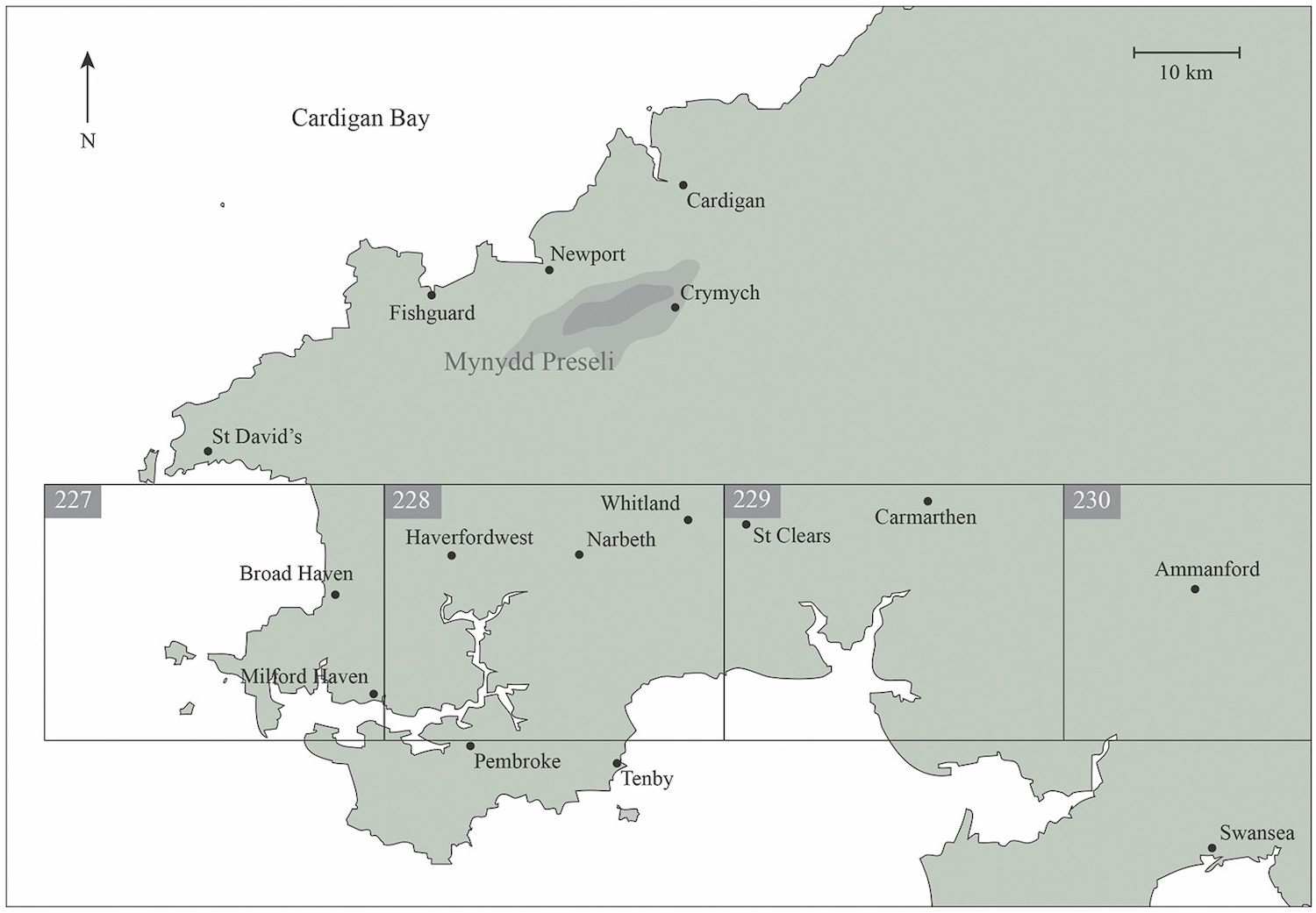

To debunk Thomas' work, Bevins and Ixer donned their Sherlock Holmes hats and examined Thomas' maps and rock samples. Thomas (1876-1935) was a geologist for the British Geological Survey who spent just one day in December 1906 surveying Mynydd Preseli (meaning "Preseli Mountains" in Welsh, although today many people call it the "Preseli Hills").

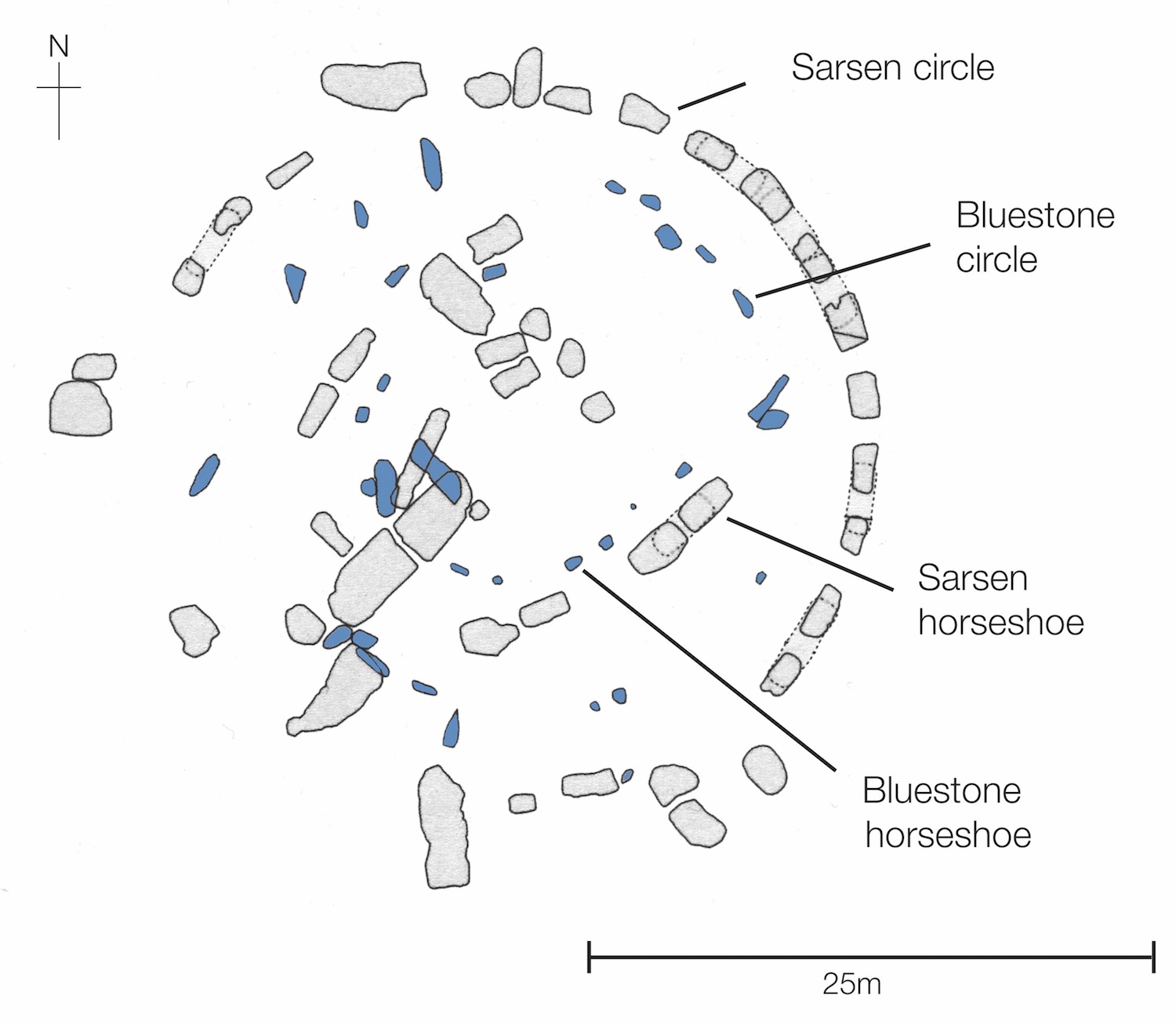

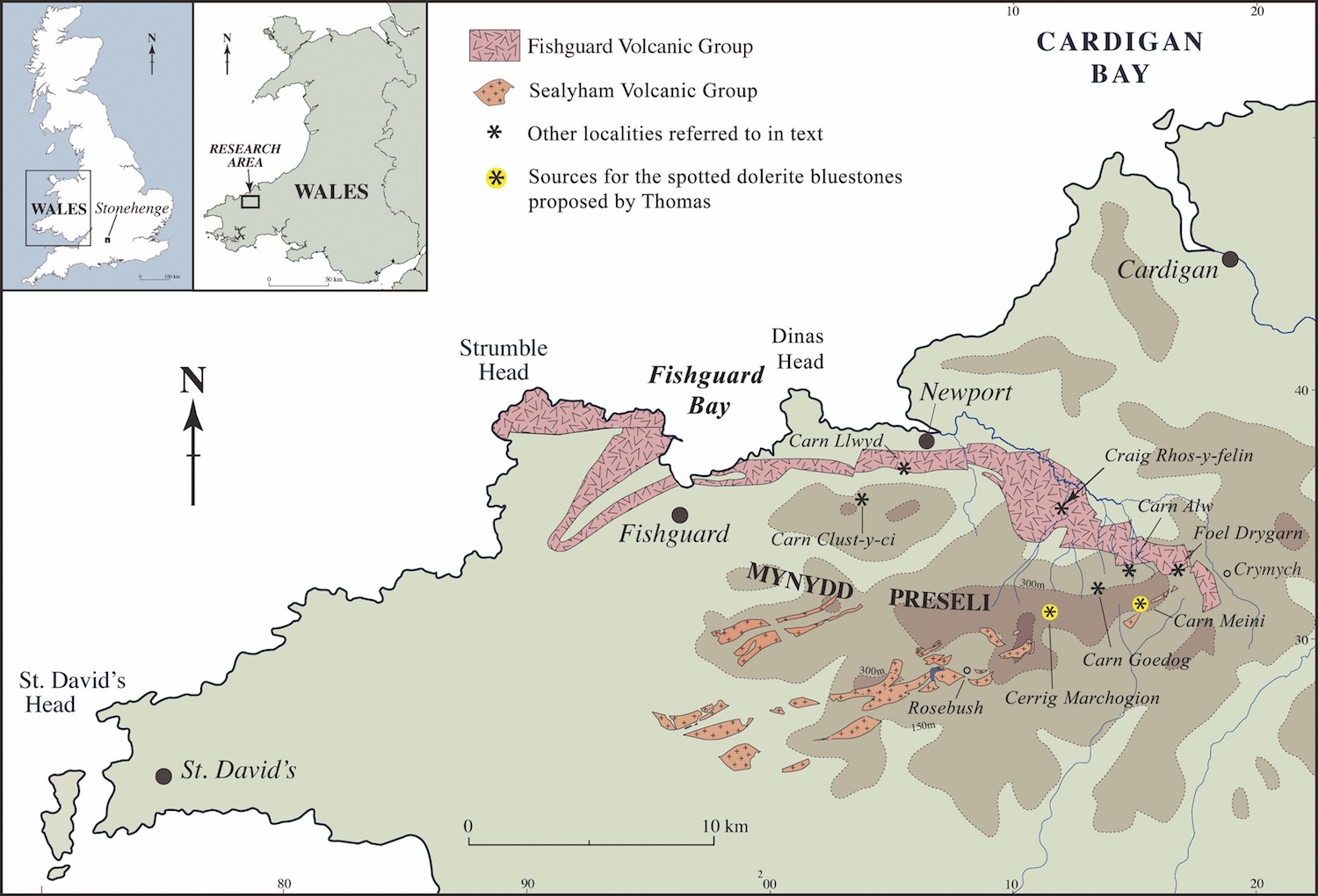

During his Preseli Hills visit, Thomas collected several samples of distinctively spotted dolerite, a type of bluish gray stone of the same kind used in Stonehenge's smaller bluestones, at an outcrop called Carn Meini. About 10 years later, the Society of Antiquaries of London had a package containing debris from Stonehenge's bluestones (named for their bluish tinge when wet or broken) sent to Thomas and asked him to determine the stones' provenance.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Upon opening the parcel from the society, Thomas immediately recognized these Stonehenge samples as being identical stones of Carn Meini, the researchers wrote in the study. Thomas also identified another spot on the southern slope of the Preseli Hills, called Cerrig Marchogion, as a spotted dolerite outcrop.

Thomas was so widely respected that nobody questioned his work for decades. Moreover, it led to the idea that, after getting the bluestones from Carn Meini, the prehistoric people then traveled southward, downhill, to Milford Haven, where they apparently picked up Stonehenge's purplish-green altar stone (made of sandstone) and then possibly boated the stones though Bristol Channel as one leg of the trip back to Salisbury Plain, Ixer said. [In Photos: A Walk Through Stonehenge]

Doubting Thomas

After spending 10 years examining various rocky outcrops in the Preseli Mountains, Bevins and Ixer realized that Stonehenge's bluestones did, in fact, come from the Preseli Mountains, but from completely different outcrops than Thomas had initially identified.

"Once we realized he got everything wrong, we went back to the material he used, the specimens he used, the thin sections he used, the maps he used. And we could see that time and time again, he slightly changed this — or let's say he forgot," Ixer told Live Science. "Thomas only looked at no more than 20 or 30 thin sections in total. Whereas Richard [Bevins] and I have looked at a couple hundred thin sections of the same material, including all of his."

The archaeologists published their results in a number of studies, showing that the bluestones came from other outcrops in the Preseli Hills: Craig Rhos-y-felin and Carn Goedog, Live Science previously reported. These outcrops are farther north than the ones Thomas suggested in his 1923 study, and about 140 miles (225 kilometers) away from Stonehenge.

In the new study, the scientists noted that "Thomas was without doubt an excellent petrographer," but his work wasn't complete, given he had spent just one day in the Preseli Hills and had only collected 15 samples. Moreover, archaeologists and geologists today use high-tech tools, such as "X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for whole rock geochemistry, or ICP-MS laser ablation techniques for mineral composition determinations" that Thomas had no access to, they wrote in the study.

The study was published online June 28 in the journal Antiquity.

Bluestone route

The newly identified outcrops completely change the possible route prehistoric people took while transporting the stones to Stonehenge.

Given that Craig Rhos-y-felin and Carn Goedog are on the northern side of the Preseli Hills, it's unlikely that Thomas' proposed route would have worked, Ixer said. Basically, prehistoric people would have needed to drag the stones southward, up the mountain and then downhill again — an arduous task, Ixer said.

"Nobody would drag the stones up the Preseli Hills only then to drift them down south to Milford Haven," Ixer said. And going to the sea from the northern slopes isn't ideal, either. "You've actually got to make a long sea journey all the way around the south coast of Wales," he said. "So, it seems a pretty unlikely suggestion."

Previously, Thomas and another famous British geologist, Sir Kingsley Dunham, had floated the idea that Stonehenge's altar stone came from Milford Haven. But new, unpublished research suggests that the altar stone came from the Senni Beds, a sandstone formation that stretches across part of Wales to Herefordshire in eastern Wales, The Times reported.

Now, it looks like the prehistoric people quarried the bluestones at Craig Rhos-y-felin and Carn Goedog and then traveled inland, picked up the altar stone at Herefordshire and then traveled southward on an ancient "superhighway," to Stonehenge, Ixer said. [In Photos: Hidden Monuments Discovered Beneath Stonehenge]

Both findings — the newly published study and the unpublished work — emphasize the idea not to blindly accept published work as gospel, Ixer noted.

"No serious paper in the last 60 years has discussed Stonehenge without quoting Thomas or starting with Thomas," Ixer said. "It's perhaps the single most famous 20th century Stonehenge paper." But though the general location of the Preseli Hills was correct, the specific outcrops Thomas named were not, and that influenced how people thought of possible routes prehistoric people took back to Stonehenge, Ixer said.

"In this case, the damage has gone down the decades, really," Ixer said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.