Oldest Fossil of a Baby Snake Discovered Trapped in Amber Tomb

A newly hatched baby snake that crawled out of an egg 99 million years ago in Southeast Asia never had the chance to grow up. Instead, it met a sticky end in a patch of resin that eventually formed the wee snake's amber tomb.

But while this Cretaceous-era hatchling from an ancient forest may not have survived long enough to see adulthood, its preserved remains — the oldest known fossil of a baby snake — are offering scientists a unique window into the distant past.

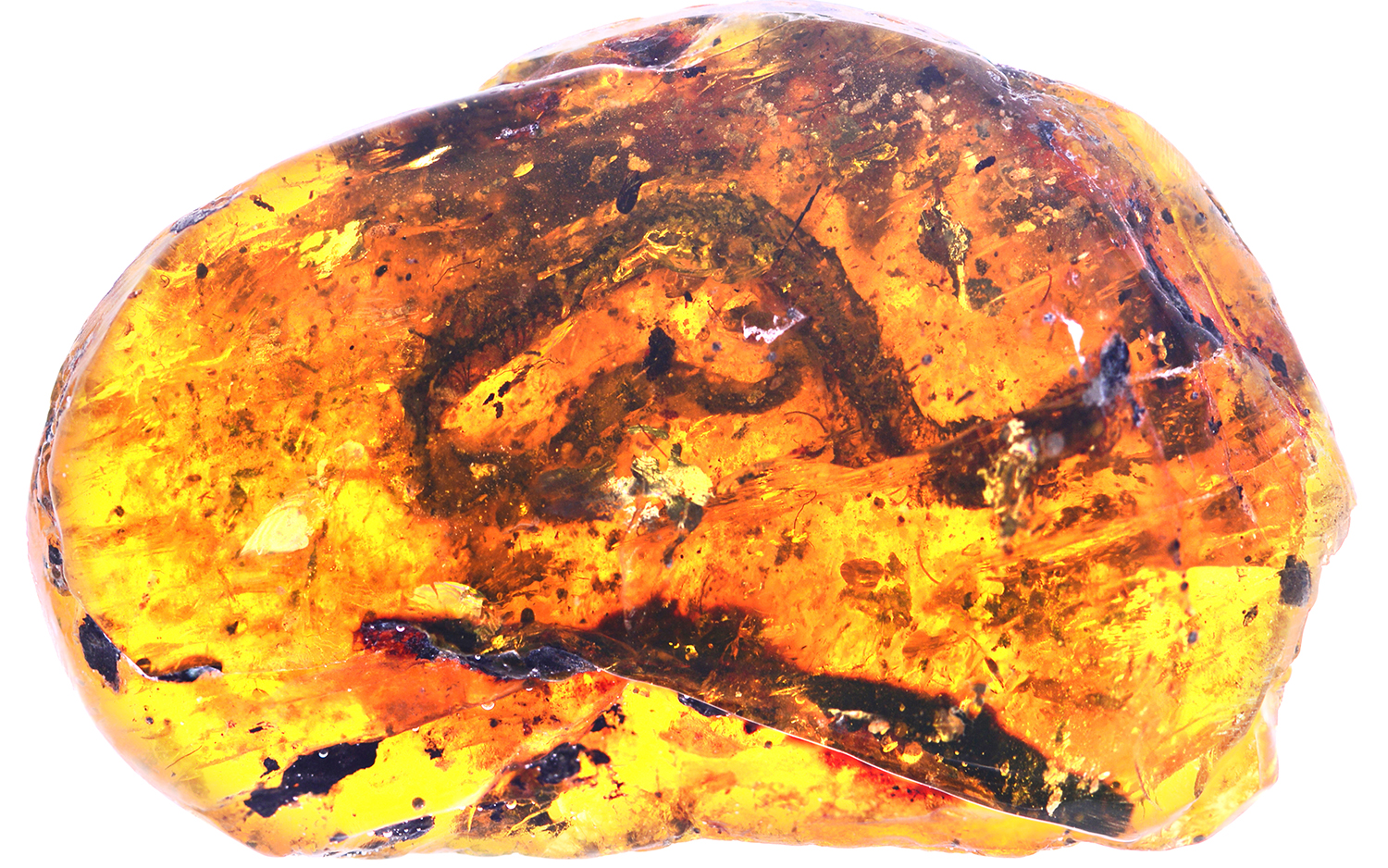

The chunk of amber holds two remarkable fossils: the tiny hatchling and a scrap of shed skin thought to belong to a larger snake. Both present intriguing evidence about the ancestors of modern snakes that lived millions of years ago, researchers reported in a new study. [Photos: Ancient Ants & Termites Locked in Amber]

Scientists have been finding amber specimens from Myanmar holding fossilized insects and plants for some time, but the discovery of vertebrate fossils inside amber is relatively recent, study co-author Michael Caldwell, a professor in the biological sciences department at the University of Alberta in Canada, told Live Science in an email.

And when amber preserves larger creatures with backbones, the results can be quite astonishing, such as the fossils of a tiny chick with "unusual plumage," mummified bird wings, a lizard with its tongue sticking out and a chunk of feathered dinosaur tail.

Entombed and intact

The piece of amber described in the study was originally privately owned and was later donated to the museum of the Dexu Institute of Palaeontology, near Beijing, where the researchers were able to analyze it, Caldwell said.

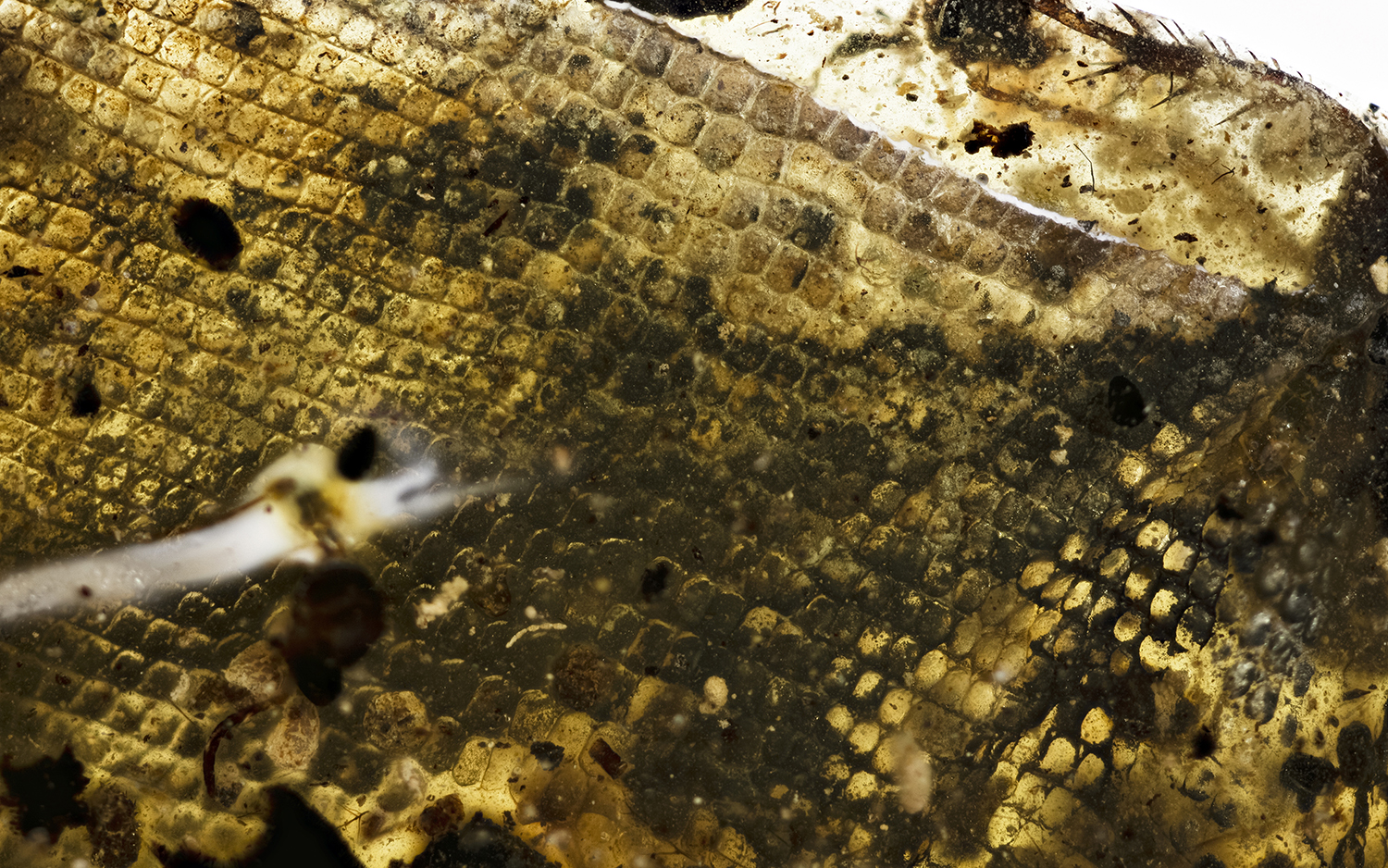

Inside the amber, the scientists found about half of the vertebrae of an intact fetal or newborn snake — about 97 bones in all — measuring about 1.9 inches (4.8 centimeters) in length. The head was missing, but the study authors were nonetheless able to identify it as a new species, naming it Xiaophis myanmarensis, Caldwell told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Even though it is a baby, there are very unique features of the top of the vertebrae that have never been seen before in other fossil snakes of a similar kind," he said. "Xiaophis fits into the base of the snake family tree, and into a group of snakes that appear to be very ancient."

The scientists were less successful in identifying the fragment of shed skin near the baby — the skin scrap was so small that they were unable to say for sure if it belonged to the same snake species as the preserved skeleton, they reported in the study.

Other organic debris trapped in the amber alongside the baby snake proved to be less exciting than the skeleton and skin, but it still offered valuable details about the ancient snake's habitat, Caldwell said in the email.

"Amber collects everything it touches — kind of like super glue — and then holds onto it for a hundred million years," he said. "When it caught the baby snake, it caught the forest floor with the bugs, plants and bug poop — so that it is clear the snake was living in a forest."

The findings were published online today (July 18) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.