We Are Now Living in a New Geologic Age, Experts Say

We are all in the midst of a new geological age, experts say.

This age, dubbed the Meghalayan, began 4,250 years ago when what was probably a planetwide drought struck Earth, according to the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).

The Meghalayan is just one of three newly named ages, the IUGS said in an announcement released July 13. The other two ages are the Greenlandian (11,700 years to 8,326 years ago) and the Northgrippian (8,326 years to 4,250 years ago), the IUGS said. [Spectacular Geology: Amazing Photos of the American Southwest]

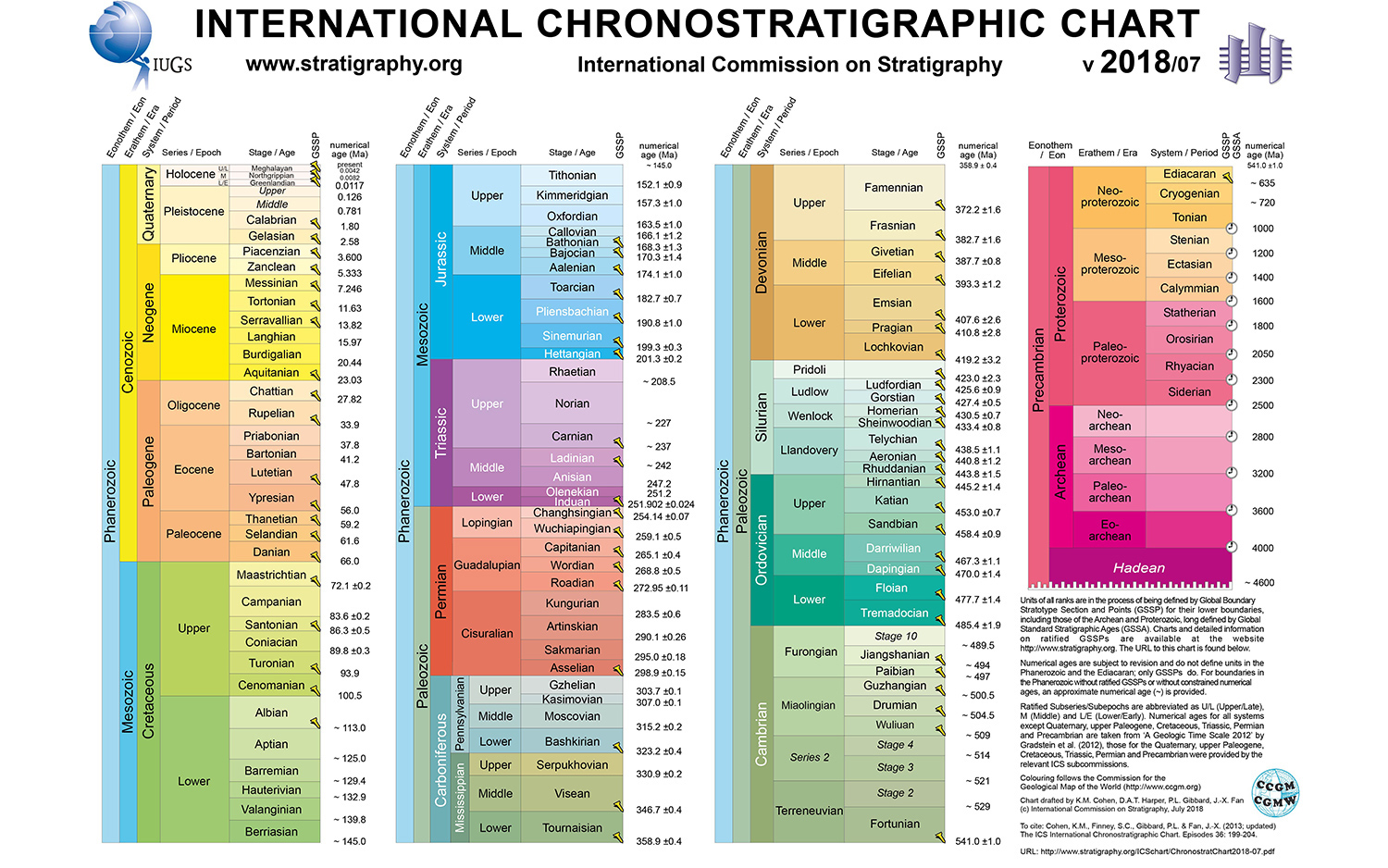

Geologists have systematically divided up, and named, all of Earth's roughly 4.54-billion-year history . From the longest to shortest, these lengths of time are known as eons, eras, periods and ages. Currently, we're in the Phanerozoic eon, Cenozoic era, Quaternary period, Holocene epoch and (as mentioned) the Meghalayan age.

The IUGS shared an image of the newly named ages in a tweet. However, the group later issued a correction about the Meghalayan's length. (That age goes to the present, not to 1950 as the IUGS mistakenly tweeted.) You can see a larger version of the newly updated chart (also called the International Chronostratigraphic Chart) here.

To determine the beginning time for each age, scientists looked at the unique chemical signatures found in rock samples from that time; each signature relates to a big climatic event, the IUGS said in a statement.

The Greenlandian, the oldest age of the Holocene (also known as the "lower Holocene"), began 11,700 years ago, as the Earth left the last ice age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Northgrippian (also known as the "middle Holocene") began 8,300 years ago, when Earth abruptly began cooling, likely because vast amounts of fresh water that came from Canada's melting glaciers poured into the North Atlantic and disrupted ocean currents, the BBC reported.

Meanwhile, the Meghalayan (also called the "upper Holocene") started 4,250 years ago, when a mega-drought devastated civilizations across the world, including those in Egypt, Greece, Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and the Yangtze River Valley, the BBC reported. This drought lasted 200 years and was likely prompted by shifts in ocean and atmospheric circulation.

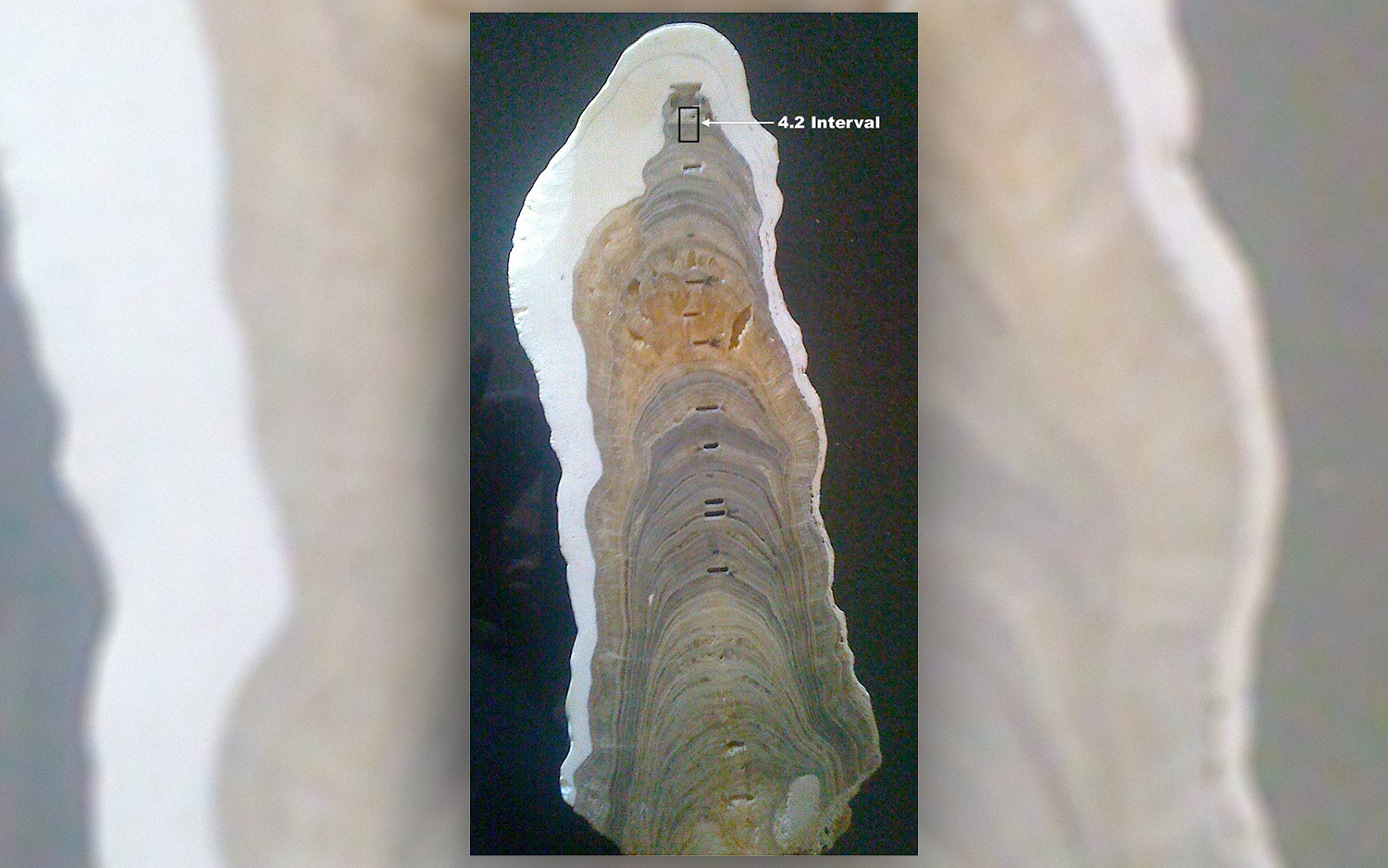

Geologists chose the name "Meghalayan" as a nod to a rock sample they analyzed from Meghalaya, a northeastern state in India, whose name means "the abode of clouds" in Sanskrit. By analyzing a stalagmite growing on the ground of Mawmluh Cave, geologists found that each of the stalagmite layers had different levels of oxygen isotopes, or versions of oxygen with different numbers of neutrons. This change marked the weakening of monsoon conditions from that time, the BBC reported.

"The isotopic shift reflects a 20 [percent to] 30 percent decrease in monsoon rainfall," Mike Walker, a professor emeritus of quaternary science at the University of Wales in the United Kingdom, who led the naming of the ages, told the BBC. [In Photos: The U.K.'s Geologic Wonders]

Walker added that "the two most prominent shifts occur at about 4,300 and about 4,100 years before present, so the midpoint between the two would be 4,200 years before present."

Controversial age

Not everyone is satisfied with the new naming scheme for the ages. The Meghalayan was introduced only six years ago, in a 2012 study in the Journal of Quaternary Science.

Some geologists say that it's too soon to name the Holocene's ages, as it's not yet clear whether the climatic shifts were truly global, the BBC reported. Meanwhile, the name "Anthropocene epoch" has been floated as a geologic period marked by the dramatic impact that humans have had on Earth, but this name hasn't been formally submitted to the IUGS yet, the organization said on Twitter.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.