Sharks Get Bigger Home Protected by Mexican Navy

Sharks can finally breathe a sigh of relief. Their home in Mexico's Revillagigedo National Park — North America's largest marine protected area — is now protected by none other than the Mexican navy, thanks in large part to a team of dedicated researchers.

This expansive upgrade didn't happen overnight. Rather, the hard work of researchers, who spent years tagging and tracking sharks, has finally translated into political policy, making the park's extension a reality.

"I'm very excited," James Ketchum, who helped tag the sharks while a graduate student at the University of California, Davis, and is now the conservation director of Palagíos Kakunjá, a nongovernmental organization for marine conservation, said in a statement published by UC Davis. "It shows all these years of work have been useful for something." [In Photos: Mexico's New Ocean Reserve Protects Stunning Biodiversity]

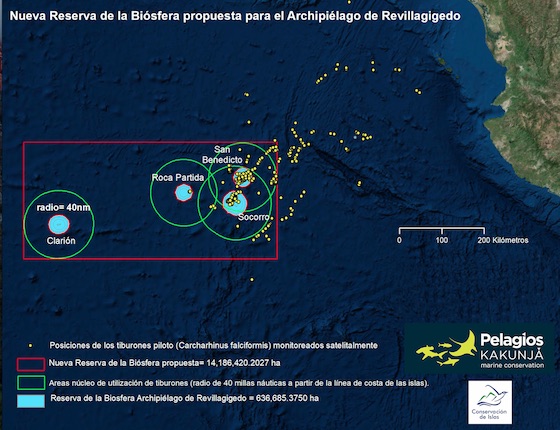

Revillagigedo National Park — also known as the "Galapagos of North America" — protects more than 58,000 square miles (150,000 square kilometers) around the Revillagigedo Archipelago, four volcanic islands about 300 miles (480 km) southwest of Baja Peninsula. Mexico announced the park's creation last November, Live Science previously reported, with the purpose of protecting sharks, giant manta rays, humpback whales, dolphins, fish and migrating birds.

"It used to be protected 6 miles [10 km] around every island," Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, who took part in the shark-tagging research as a doctoral student with Mexico's Interdisciplinary Center for Marine Sciences, said in the statement. "But thanks to all the information we gathered about the connectivity between all these islands, we were able to protect 40 square miles [100 square km] around the islands."

The researchers realized that the sharks need more than just 6 miles around each island after analyzing acoustic and satellite shark-tracking data from 2009 to 2015. They found that the sharks used large swaths around each island, sometimes up to 100 miles (160 km).

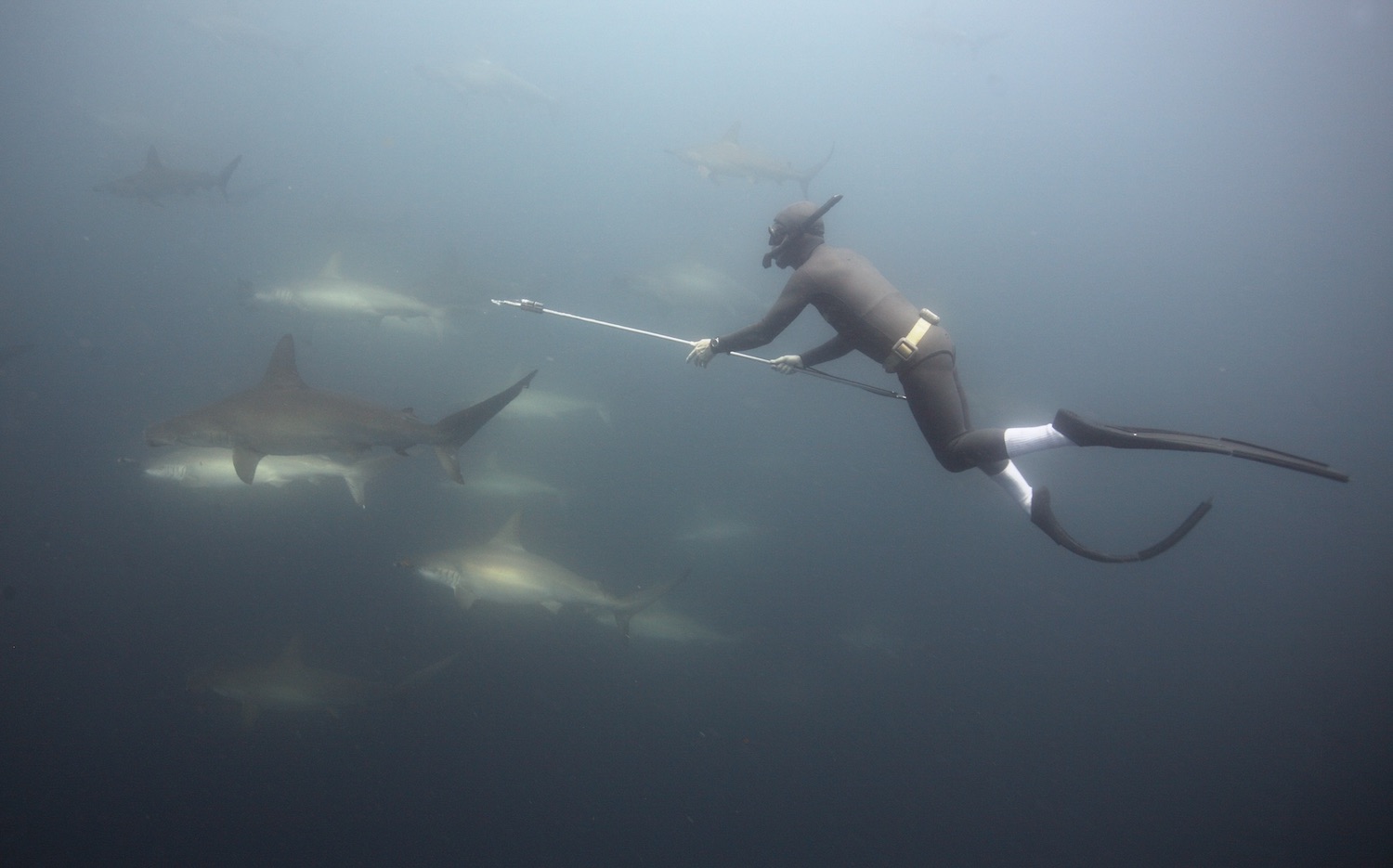

After tagging scalloped hammerhead sharks, the researchers showed that 40 nautical miles around each island would best protect the animals and their ecosystem.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using this research, the first park design was proposed in 2014 to the Mexican Commission of Natural Protected Areas. This proposal was even included in the site's official documentation as a heritage site with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The researchers later presented an expanded park design, which eventually morphed into the new national park, which became official on Nov. 24, 2017.

After the creation of Revillagigedo National Park, the Mexican navy agreed to patrol the area with boats and drones to ensure that the park remains protected, the researchers noted. Pew Charitable Trusts is also planning to help monitor the islands by satellite.

Sharks often get a bad rap in Hollywood and the media, but they're key predators that keep ecosystems within the ocean healthy.

"When you protect the highly mobile top predator, you protect the reef fishes and reef fauna that are less mobile," Ketchum said. "The idea is you're protecting everything. This archipelago had been highly exploited. The need for protection has been there for at least 20 years or more, and finally it has arrived."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.