This Mustached Monkey Likely Inspired Dr. Seuss' Lorax

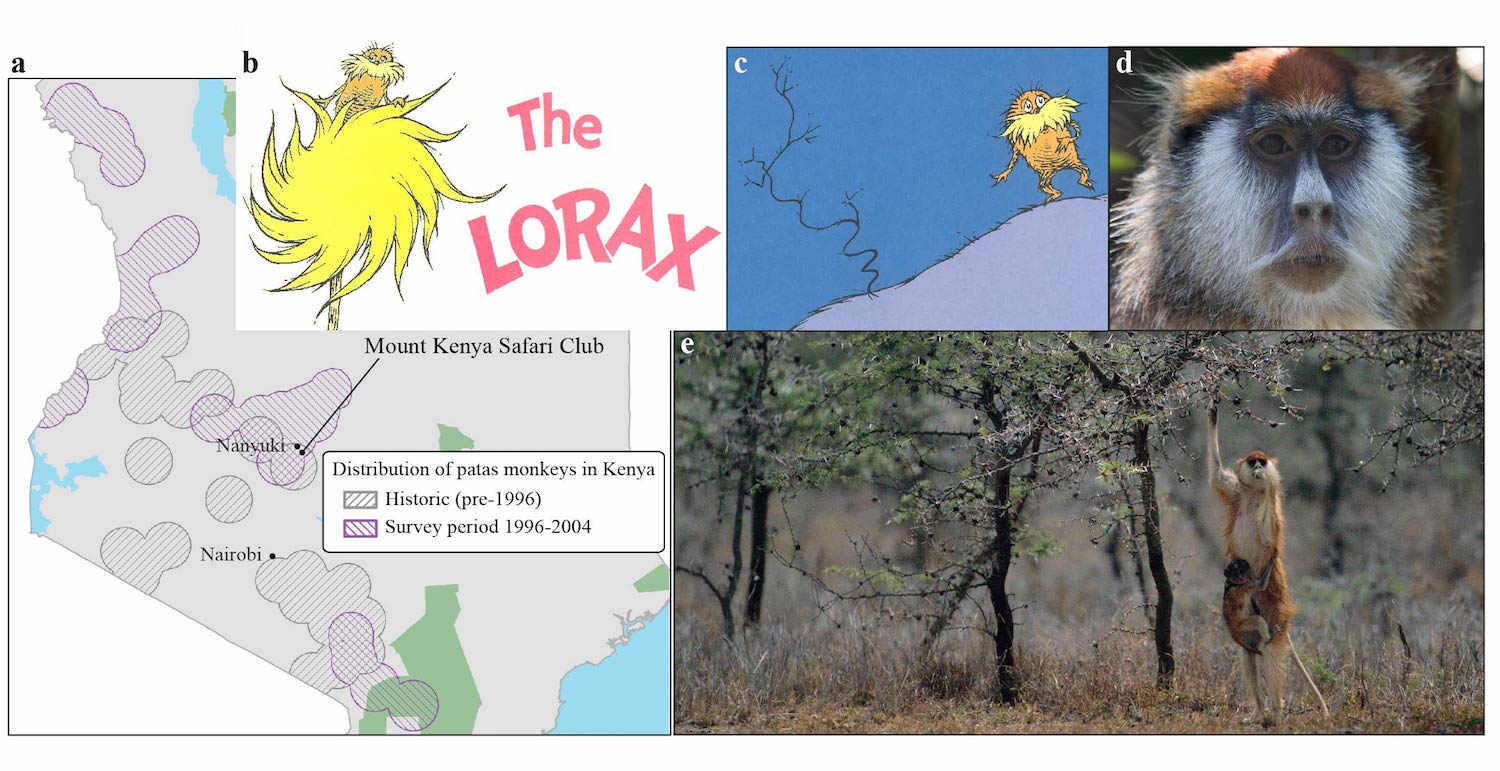

This realization, as well as the idea that Seuss' fictional truffula trees were inspired by the trees the patas monkeys depend on, may change how scholars interpret "The Lorax" (Random House, 1971), according to the study, published online today (July 23) in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Rather than seeing the Lorax as an eco-watchdog bent on being "sharpish and bossy" with big polluters (a view some scholars and environmentalists take), it makes more sense to appreciate the furry creature as a natural member of the ecosystem — one who is dismayed that his home is being destroyed, said study lead researcher Nathaniel Dominy, a professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. [Photos: Adorable and Amazing Guenon Monkey Faces]

"The Lorax was a participating member of the ecosystem," Dominy told Live Science. "I think his self-righteous indignation is much more forgivable and understandable if you take this different perspective."

However, not everyone is on board with this interpretation.

"The way the Lorax appears, following the chopping of the first tree, says to me that he's more of an eco-watchdog, since we don't see him playing in the idyllic landscape before the Once-ler [culprit] begins to destroy it," said Matthew Teorey, a professor of English at Peninsula College in Port Angeles, Washington, who has studied "The Lorax" but was not involved with the new study. "The Lorax pops into existence just as an environmentalist would."

Writing "The Lorax"

In a nutshell, "The Lorax" tells how a mysterious green creature known as the Once-ler begins harvesting beautiful truffula trees at the expense of the animals that depend on them. Despite the Lorax's protests, the Once-ler cuts down all the truffula trees, and the animals that lived there — the bar-ba-loots, the swomee-swans and the humming fish — all leave, saying goodbye to their former Eden.

But this creative story was a long time in the making. Theodor "Dr. Seuss" Geisel (1904-1991) wanted to write an environmental book for children, but he found little inspiration in the existing "dull" literature that was "full of statistics and preachy," Geisel said, according to "Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography" (Random House, 1995). So, his wife, Audrey Geisel, suggested that they travel to Kenya to lift him out of his funk.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The trip worked. After arriving at the exclusive Mount Kenya Safari Club in September 1970, Geisel had a breakthrough. He flipped over a laundry list and wrote 90 percent of "The Lorax" in one afternoon.

On a side note, Geisel began using the moniker Seuss — his mother's maiden name and his middle name — after he got kicked off the Dartmouth College humor magazine, the "Jack-O-Lantern," in 1925, when he was caught violating Prohibition's restrictions. He added the "Dr." to his name in 1927, saying that the honorific compensated for the doctorate he never received during his graduate studies in English literature at the University of Oxford in England, said study co-researcher Donald Pease, a professor of English at Dartmouth College. [10 Scientific Tips for Raising Happy Kids]

Monkey see, monkey do

All of this was old news to Pease, who wrote a biography about Geisel's life. But it was news to Dominy, who happened to strike up a conversation with Pease at a campus-wide dinner at Dartmouth.

Dominy was stunned to learn that Geisel had visited Kenya. Dominy often calls the patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas) the most Seuss-like primate; both are orange and have big, cream-colored mustaches. Even the voice of the Lorax (a "sawdusty sneeze") sounds like the 'whoo-wherr' calls of patas monkeys, he noted. Could one have inspired the other?

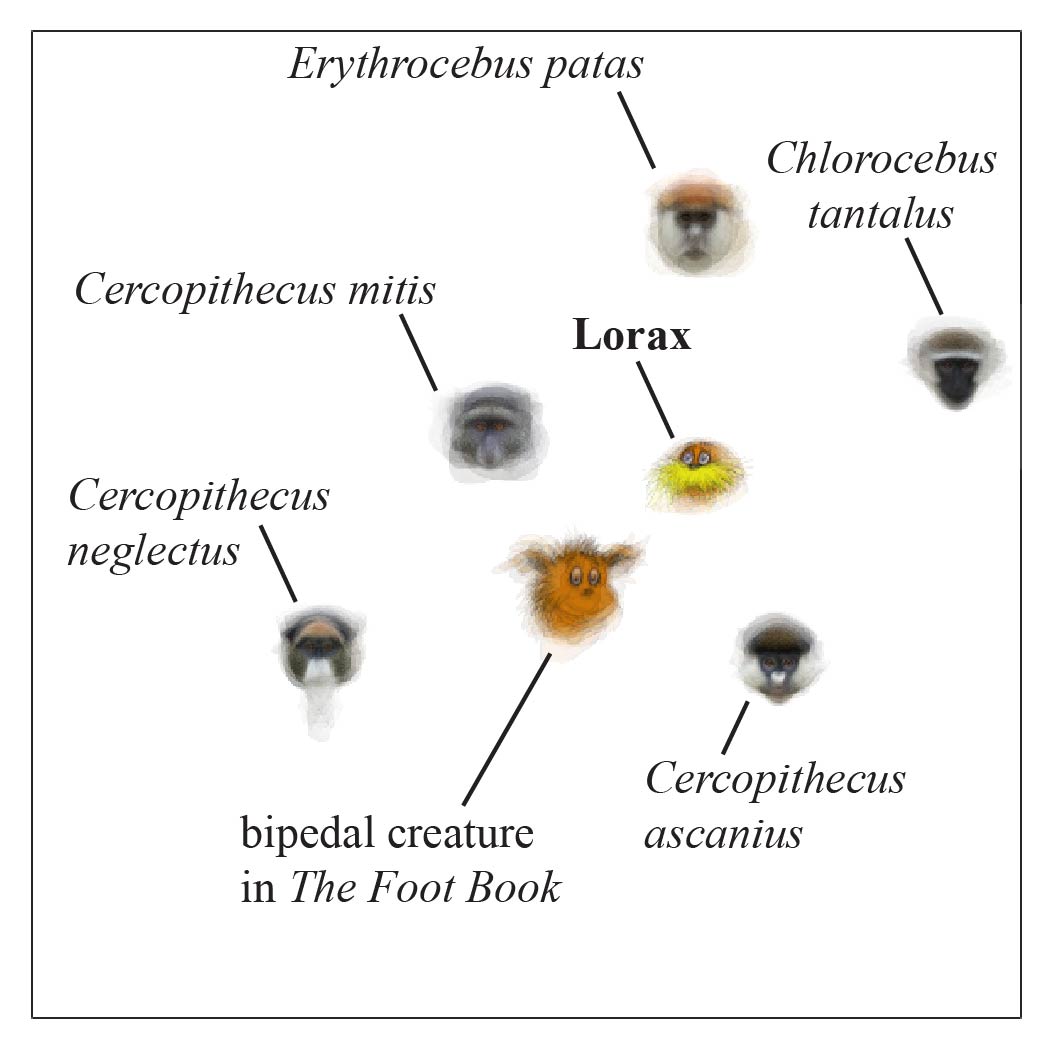

The two professors banded together to investigate, partnering with study-co-researcher James Higham, an associate professor of anthropology at New York University. Higham had previously developed a machine-learning technique that could tell apart similar-looking monkey species. The team fed the algorithm images of the Lorax, several monkey species and another orange Seuss-created creature from "The Foot Book" (published in 1968, before the Kenyan trip).

The result? The Lorax looked more like the patas monkey than it did the creature from "The Foot Book," supporting the idea that the patas monkeys inspired Seuss. (The algorithm showed that the Lorax looked even more like a blue monkey, or Cercopithecus mitis, but it's unlikely Geisel saw any of these on the safari, as blue monkeys live deep in the forest, Dominy said.)

In addition, when Geisel visited the Laikipia Plateau of Kenya, he said, "Look at that tree. They have stolen my trees," the researchers wrote in the study. Geisel was referring to his tree illustrations from previous books, published before he conceived of the truffulas, the authors said. It's unclear which tree Geisel saw, but it could have been the whistling thorn acacia (Acacia drepanolobium). This spindly tree provides food for patas monkeys, who eat its fruit, the ants that live on its branches and the sweet gum that exudes from the plant's bark, Dominy said.

While A. drepanolobium doesn't look like a fluffy (and fictional) truffula tree, it does resemble the wispy trees that remain near the Once-ler's home after all of the truffula trees disappear. It's anyone's guess whether this bare tree is meant to be a ravaged truffula or another species entirely, but again, it's possible that A. drepanolobium inspired Geisel when he wrote and illustrated the book, Dominy said.

Teorey agreed with the study's look-alike finding.

"It seems reasonable that the trees and monkeys would inspire the story's images and perhaps its characters, too," Teorey told Live Science.

Moreover, Teorey said he likes "the idea of the Lorax being an indigenous person or creature of the specific land exploited by the Once-ler." [Photos: Wild Animals of the Serengeti]

Art mirroring life

In "The Lorax," after the Once-ler begins destroying the environment, the bar-ba-loots leave first, followed by the swomee-swans (who, with smog in their throats, can no longer sing) and then the humming fish. Although Geisel probably didn't know it, this is what scientists call a trophic cascade, "where, as species disappear from the system, the system is unstable and has to reassemble," Dominy said. "And then, that propagates further species disappearing."

Just as in "The Lorax," real-life patas monkeys and acacia trees are rapidly disappearing. In the past 15 years, patas monkey populations have fallen by half in Kenya, Dominy said. And climate change is taking a toll on the acacia trees; as the climate becomes more arid, large animals, including giraffes, rhinos and elephants, feast on this tree's leaves. (During wet conditions, these large herbivores tend to diversify their diets — elephants eat more grass and black rhinos eat different woody species. But during dry spells, all three converge on the "poor Acacia drepanolobium, which itself is already water stressed." Dominy said.)

The more these animals eat the tree, the less it can withstand drought. "There's very few younger trees coming into the system, because adults just don't have the resources available to them to produce seeds and flowers," Dominy said. On top of that, many people harvest the trees to produce charcoal, he noted.

This is why the Lorax's message still rings true: "UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It's not."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.