This Blood Test Can Detect Brain Injuries, But Some Doctors Say It Might Be Pointless

A new blood test approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to detect brain injuries might reduce the number of potentially unnecessary brain scans, according to a new study.

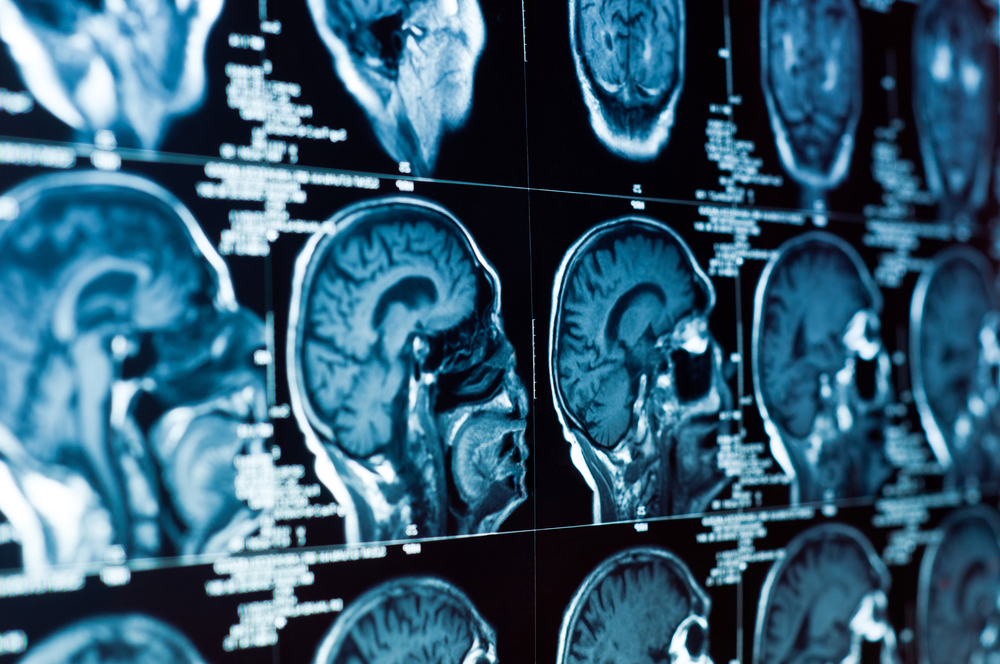

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) — which can range from relatively mild conditions (such as a concussion) to severe ones (such as bleeding in the brain) — can be difficult to diagnose. One way to diagnose the injuries is a CT scan, but these imaging tests can be very costly and expose patients to radiation.

In the new study, published July 24 in the journal The Lancet Neurology, the researchers argue that the blood test could reduce the number of unnecessary CT scans performed on patients suspected of having a TBI. However, several experts told Live Science that they weren't convinced the new test would be a significant boon to patients. [3D Images: Exploring the Human Brain]

The blood test, which was developed by Banyan Biomarkers Inc., works by looking for two proteins that indicate brain injury has occurred, according to the study. The proteins, called UCH-L1 and GFAP, are thought to be released mostly with brain injuries. (The company also provided funding for the study.)

The new study details the clinical trial that led the FDA to approve the test — the first of its kind to be approved in the U.S., though a similar test is already widely used in Europe. The clinical trial, which ran from 2012 to 2014, included nearly 2,000 patients with suspected brain injuries at 22 sites in Europe and the U.S. The patients in the trial had both the blood test and a CT scan within 12 hours of their injury (when the two proteins are most elevated). The blood test indicated a positive result if either one or both proteins were above a certain threshold and a negative result if both were below the limit.

The CT scan was used in the trial as the "gold standard" for determining how well the blood test found such injuries. The researchers found that the blood test had a nearly 98-percent specificity. In other words, it missed very few injuries. The blood test "missed" only three patients who'd had a CT scan that indicated injury but also had a negative blood-test result.

The findings suggest that the blood test could reduce the number of CT scans by 35 percent, said study co-author Dr. Robert Welch, an emergency-medicine physician and professor of emergency medicine at Wayne State University, in Detroit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In practice, the idea would be to draw blood from patients who have a suspected TBI and for doctors to use the results to decide whether to proceed with a CT scan, Welch told Live Science. (He noted that, while there are guidelines for when doctors should order a CT scan for a patient, the guidelines aren’t clear-cut and can be misinterpreted. As a result, many more CT scans are ordered than are necessary, Welch said.)

Still, not everyone is convinced that this blood test is necessary or that it will make a difference in the emergency room.

Is this blood test necessary?

Dr. Adam Sharp, an emergency-medicine physician and research scientist at Kaiser Permanente in California, who was not part of the study, said he agrees with a commentary that was published alongside the study. In the commentary, other researchers argued that the value of having such a blood test in clinical practice would be small, or even absent. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

"I strongly question how the blood test could improve [emergency room] care, costs or efficiency," Sharp told Live Science in an email. If physicians just used the guidelines put in place for when to do a CT scan, then the patients "would avoid the… unnecessary blood tests and might go home safely without any further testing."

The only people who would benefit from the broad use of these blood tests would be the developers who profit from it, Sharp added. "As of now, I would not recommend the added costs and inconvenience of drawing blood, when a decision rule (the guidelines) can perform the same," he said.

Dr. Edward Melnick, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University who was also not involved with the research, said that he thought the study was interesting but that it's not likely to change emergency care — at least in the short term.

"Since we already have high-performing clinical decision rules for [diagnosing TBI], diagnostic biomarkers do not add much to the literature," Melnick told Live Science. However, because the blood test is an "objective" measure that doesn't rely on doctors' guidelines, it could be preferable to patients and doctors, he added.

Welch, however, noted that his team's results demonstrated that the blood test could reduce CT scans by 35 percent compared with "usual care" practices, thus proving the value of the test. What's more, the study included only patients whose doctors thought a CT scan was necessary, he added. And the decision rules in place can miss minor bleeds, whereas the blood test would catch those in addition to bigger injuries, he said.

Still, Welch said that the turnaround time for the test results needs improvement. "For this test to be useful, it can't be a test that takes 2 or 4 hours," he said. "When I see a patient in the emergency department, I have to make a decision relatively quickly of if I have to scan them or not." That decision should be on the order of minutes, not hours, he said.

Welch hopes that this blood test, with such improvements, can be made available to patients by 2019, or by 2020 at the latest.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.