Forgotten 'Dinosaur' Fossil Actually Belongs to a Weird, Hippo-Like Beast

In the early 1950s, a mysterious fossil thought to belong to a dinosaur sat on display in the village hall in Fukushima, Japan. But a new analysis of the ancient bone reveals that it belonged to an entirely different animal: a weird, hippo-like creature that lived nearly 16 million years ago.

Much like today's hippopotamus, the creature — a member of the now-extinct genus Paleoparadoxia (Greek for "ancient paradox") — was a water-loving beast that gulped down aquatic plants for dinner, the researchers said.

The new analysis shows that much can be learned by studying long-forgotten museum fossils, said the study researchers, who detailed the unexpected rabbit hole they went down while investigating the bone's past. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"This study demonstrates that if enough information is provided in the first place — a trail of bread crumbs, if you will — mystery fossils and other museum objects can be tracked down," said Robert Boessenecker, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at the College of Charleston, in South Carolina, who was not involved with the study.

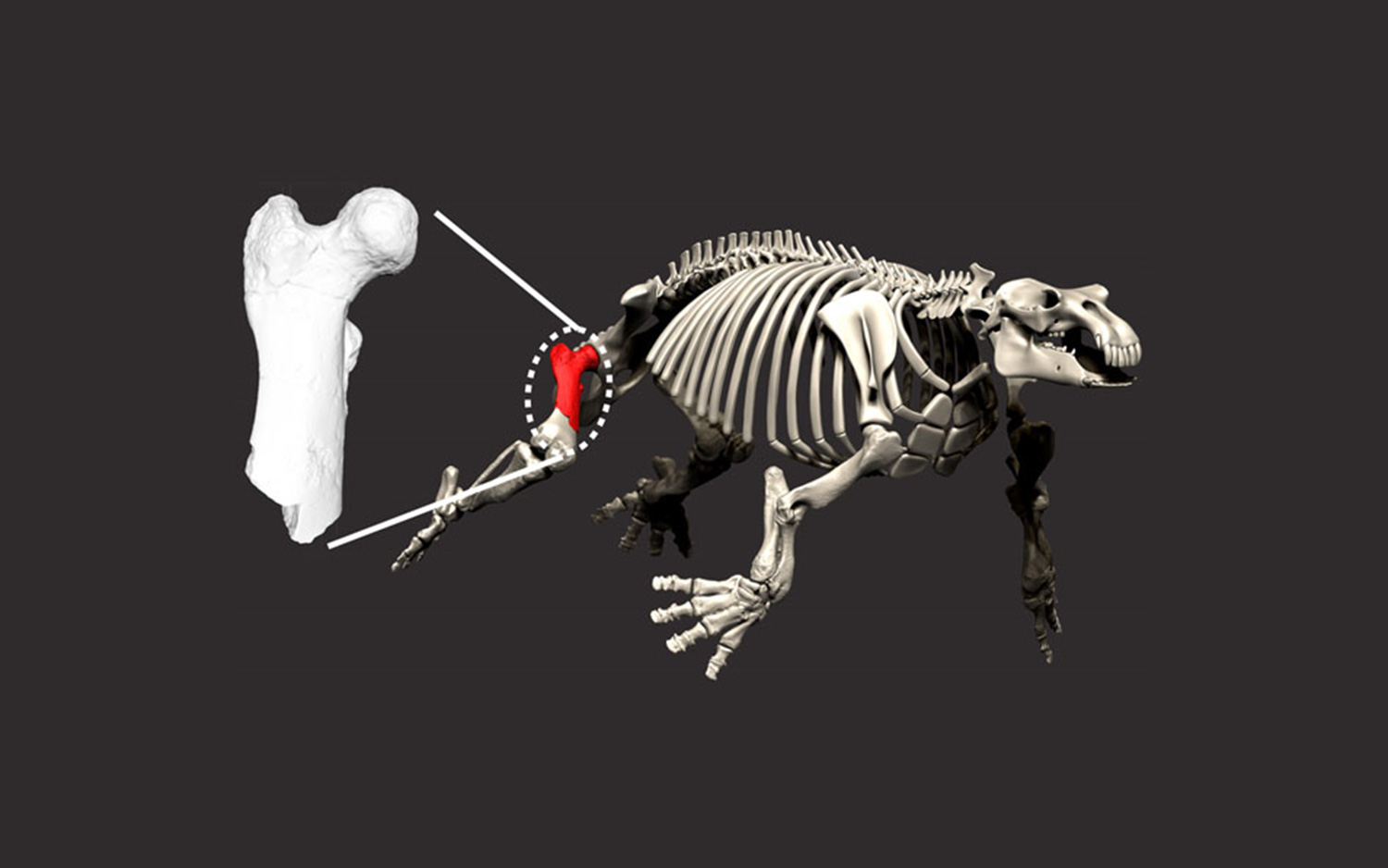

The so-called detective work began in 2017, when study co-researcher Yuri Kimura, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, found an old wooden box at the University of Tsukuba. The box contained the right femur (leg bone) of a desmostylia, an extinct order of aquatic mammals.

A slip of paper with the box noted that the uncatalogued bone was discovered by Tadayasu Azuma in Tsuchiyu Onsen town, in Fukushima City, in 1955. Kimura wanted to see if she could find more fossils at that location, so she and her colleagues traveled there to try to pinpoint the femur's origins.

After interviewing several locals and sifting through archived documents and photos from the 1950s, the researchers learned that the fossil and several other ancient bones were discovered in the early 1950s during the construction of a dam, possibly the Higashi Karasugawa River first dam.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An interview with Azuma’s oldest son offered a slightly different story. According to the son, he found the fossil while working on the third dam with his father. Because of these conflicting accounts, it's unclear which year and what dam the fossil is from, the researchers said. However, the son also knew that the fossil wasn't a dinosaur bone, and that it belonged to a desmostylus, so it's possible that the son had communicated with a scientist about the bone, but that the scientist did not formally report it, the researchers said.

Despite this, shortly after the fossil's discovery, people in the village began calling it a dinosaur bone. The femur was so famous that it was put on exhibit at the village hall. Luckily, the fossil was removed shortly before a devastating fire destroyed most of the city, including the village hall, on Feb. 22, 1954, as the researchers learned.

Zircon dating

To find the fossil's age, the researchers used zircon dating. Zircon is a mineral that contains the radioactive element uranium, which decays into the element lead at a specific rate over time, according to the American Museum of Natural History. This steady conversion rate allows scientists to date rocks with zircon crystals by analyzing the ratio of uranium and lead within the specimen.

The zircon-dating revealed that the Paleoparadoxia lived about 15.9 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch. That fit in perfectly with that researchers already know about Paleoparadoxia — a marine creature that could grow up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length and lived in the Pacific Ocean from about 20 million to 10 million years ago.

Moreover, the fossil also has visible muscle scars, "which makes the specimen useful for future studies that rely on accurate muscle maps for modelling studies of locomotion of the hind limb," the researchers wrote in the study.

"I was very impressed with this study," Boessenecker told Live Science. "The methods involved include a bit of geochemistry and a lot of good old-fashioned detective work."

The study was published online July 25 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.