How Do You Know If Your Cut Has Flesh-Eating Bacteria?

"Flesh-eating bacteria" is as scary as it sounds — a serious infection that spreads quickly in the body and can result in the loss of limbs and even death.

But the condition, known medically as necrotizing fasciitis, is also rare, with about 4 cases per 100,000 people occurring each year in the United States, according to a 2015 study.

Still, given the gravity of the condition — which destroys skin and muscle tissue — people with it need immediate medical care. But how do you know if your cut has flesh-eating bacteria?

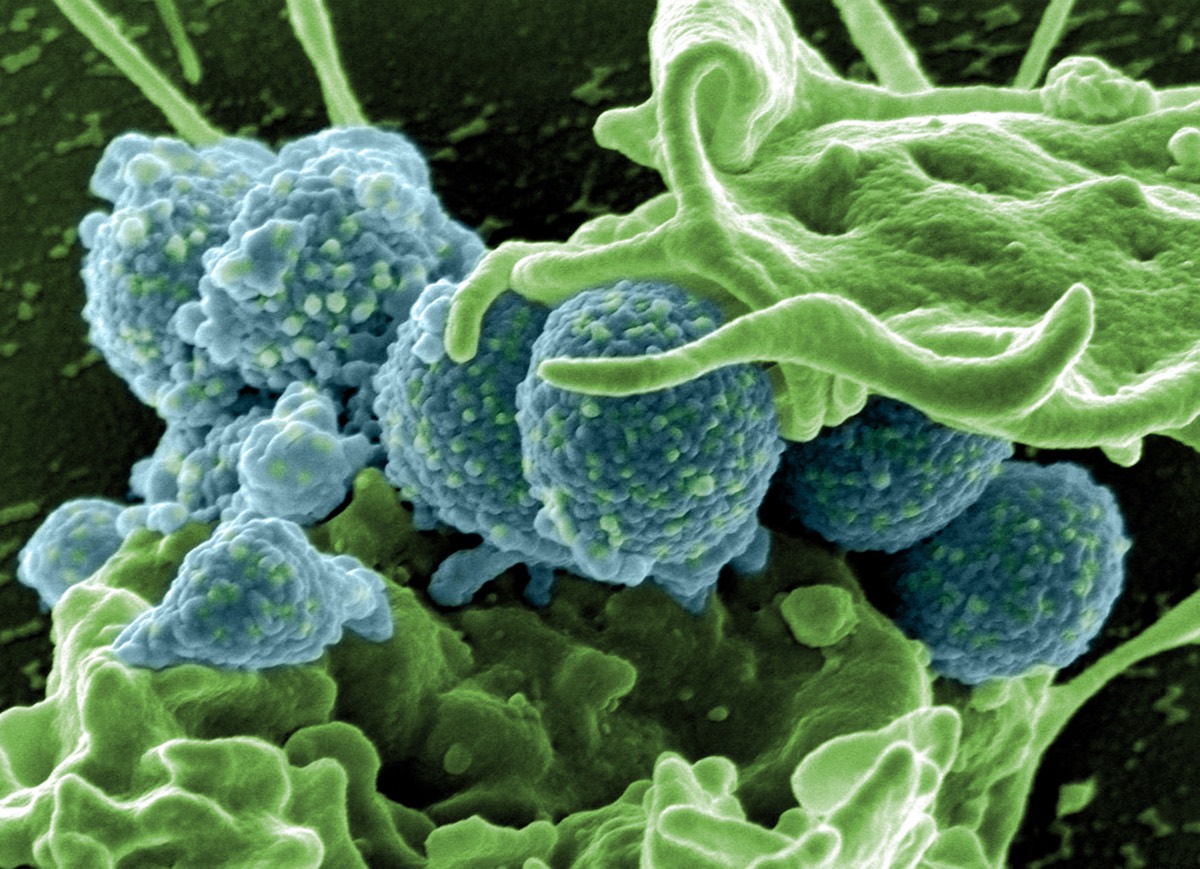

First, to clarify, there are several types of bacteria that can cause necrotizing fasciitis, including group A Streptococcus (group A strep), Klebsiella, Clostridium, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Most commonly, people get necrotizing fasciitis when the bacteria enter the body through breaks in the skin, including cuts and scrapes, burns and surgical wounds, the CDC says.

One feature of necrotizing fasciitis is "pain that's out of proportion" to the wound, said Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency care physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. People with the condition often report "exquisite pain and sensitivity," Glatter told Live Science. Some patients may also experience crackling sounds or sensations due to the presence of air under the tissue, he added. (Some species of bacteria that cause necrotizing fasciitis produce gas, which results in air under the tissue.) [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Other early symptoms include a red or swollen area of skin around the cut that spreads quickly, and pain beyond the area of skin that's red, according to the CDC. People who have these symptoms after injury should see their doctor right away, the CDC says. Symptoms often begin within hours of injury.

Patients may also experience flu-like symptoms, including fever, stomachache, nausea, diarrhea, chills and body aches, according to the National Institutes of Health's Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Later symptoms of the condition include ulcers, blisters or black spots on the skin and pus oozing from the infected area, the CDC says. As the infection spreads, a patient may become confused or delirious; and pain may appear to improve as nerves are destroyed, according to GARD.

Anyone can get necrotizing fasciitis, although the majority of people who develop it have other health problems that lower their bodies' ability to fight infection, including diabetes, kidney disease, cancer and liver disease, according to the CDC.

Another risk factor is exposing a wound to seawater that contains Vibrio vulnificus, another cause of necrotizing fasciitis.

Patients with necrotizing fasciitis need quick and aggressive treatments, Glatter said. The mortality rate is estimated to be between 25 and 35 percent, and sometimes as high as 50 percent, according to the 2015 study.

The condition is treated with strong, intravenous antibiotics, and with surgery to remove dead tissue. Sometimes, doctors need to amputate an infected limb to stop the infection from spreading, the CDC says.

Proper wound care can help prevent bacterial skin infections such as necrotizing fasciitis, according to the CDC. People are advised to clean all minor cuts with soap and water; cover open wounds with clean, dry bandages until they heal; and see a doctor for puncture wounds and other deep or serious wounds.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents