Why Are Dozens of Dead Animals Washing Up on Florida Beaches?

Scores of dead fish litter the shorelines of beaches in southwest Florida, and hundreds of dead and ailing sea turtles have washed up on shores there in recent weeks — all victims of a toxic red tide caused by the single-cell alga Karenia brevis.

Algal blooms occur seasonally in the Gulf of Mexico, when water conditions enable their populations to explode and spread. But this year's event includes especially high quantities of algae that produce a toxin, and the impact on marine wildlife is devastating, affecting sea birds as well as fish and turtles in unprecedented numbers, the Fort Myers News-Press reported.

The algae's toxins can also be dangerous to humans if inhaled, particularly for those people who have respiratory issues. Concentrations of algae in some coastal areas have been so high that the National Weather Service (NWS) issued beach hazard advisories over the weekend, warning about risks of respiratory irritation. Those warnings remain in effect as of today (July 30), according to the NWS. [10 Ways the Beach Can Kill You]

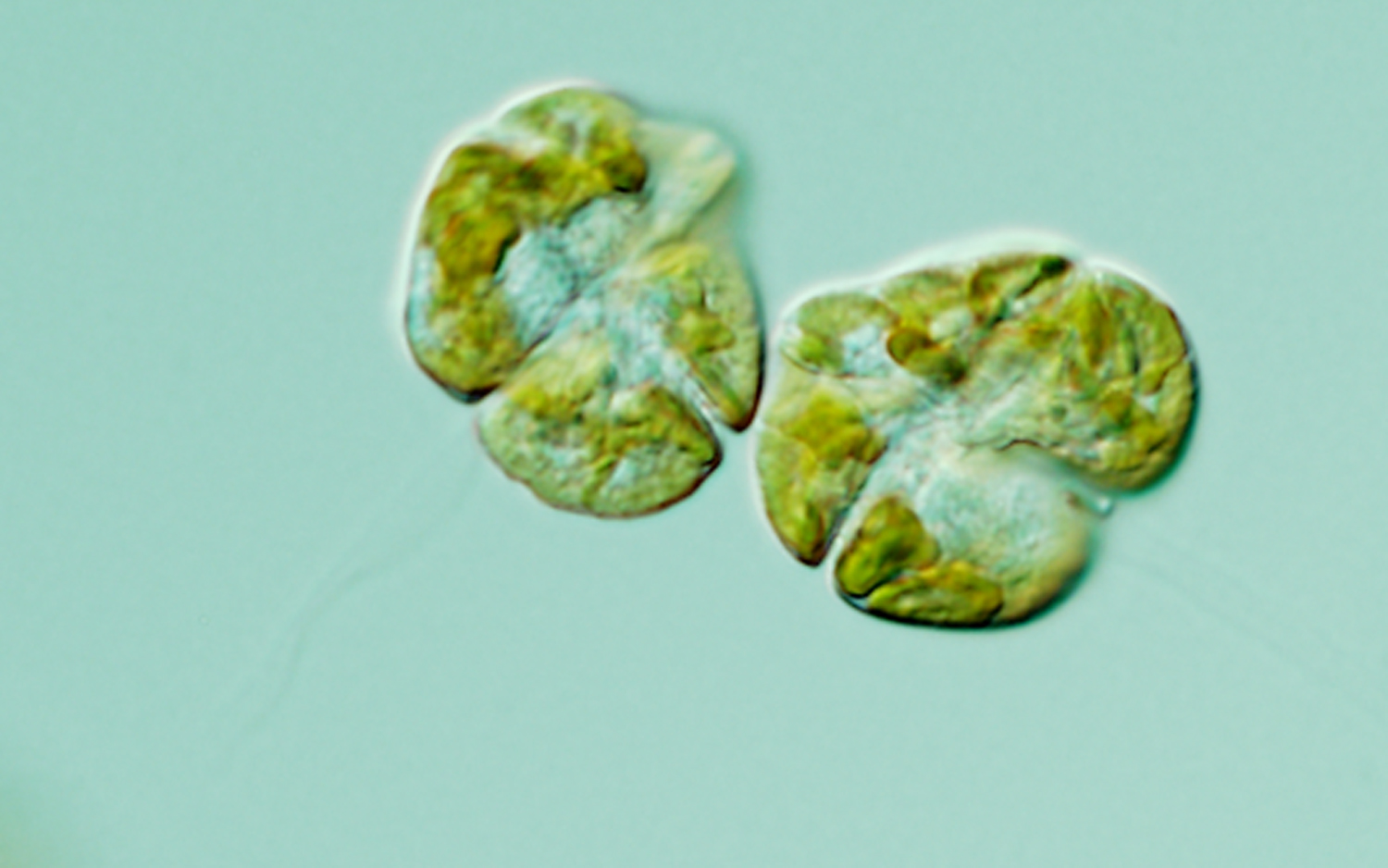

Though K. brevis algae individually appear greenish, in high enough concentrations their photosynthetic pigments often color ocean waters red or brown, earning the name "red tide," Michelle Kerr, a spokesperson for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), told Live Science.

Any algal blooms that produce toxins are typically called "red tides," she added. "Red tides caused by other algal species can appear red, brown, green or even purple. The water can also remain its normal color during a bloom," she said.

Toxins produced by these particular algae can be inhaled or ingested and affect marine animals' nervous systems, Kerr explained. Animals that consume the algae absorb its toxins; they then become poisonous to other animals. In this way, a red tide can generate toxic ripples that decimate an entire aquatic food chain, Kerr said.

A lethal bloom

Sea turtle mortality during the current red tide is far above average, with 287 dead or dying stranded turtles reported this year, Kerr said. By comparison, in previous years, the average number of stranded sea turtles reported for the same counties during the same time of year is usually half that number.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One rare casualty of the red tide this year was a young whale shark that washed ashore on Sanibel Island on June 22 — the dead shark tested positive for the K. brevis algae, according to the News-Press.

Dead fish have been washing up on Florida beaches "for months," the News-Press reported on June 27, and a special FWC hotline for reporting fish kills — masses of dead fish — has logged about 300 reports since the red tide first appeared in November 2017, Kerr told Live Science.

K. brevis typically exists at levels of about 1,000 cells per liter of ocean water near the Florida coast, according to the FWC. During algal blooms, which usually emerge in late summer or early fall, populations can climb to concentrations sufficient to kill fish — about 250,000 cells per liter of water — within just a few weeks, the FWC reported.

Harmful algae blooms are considered "high-concentration" if the ratio of algae to water is more than 1 million cells per liter, Kerr explained. A recent sample of waters near Florida's Sanibel Island, where the dead whale shark was found, showed 5 million algae cells per liter, Rick Bartleson, a chemist with the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation, told the News-Press.

Wildlife casualties of the red tide are likely even higher than suggested by the number of dead and dying animals found on beaches, as the majority of the algae's victims likely sink to the sea bottom, the News-Press reported.

People in close proximity to strong red tides can experience tearing eyes, sneezing or coughing; and those with asthma, emphysema or other respiratory conditions may be more vulnerable to the airborne toxins, according to the NWS advisory.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.