Astrophysicists Just Saw an Amazing Structure in the Sun's Outer Atmosphere

The sun is a giant, churning ball of gases, with an atmosphere that flings streamers and blobs of particles into space. Now, astrophysicists have found that inside the sun's atmosphere, what may seem like cosmic clutter hides some beautiful order.

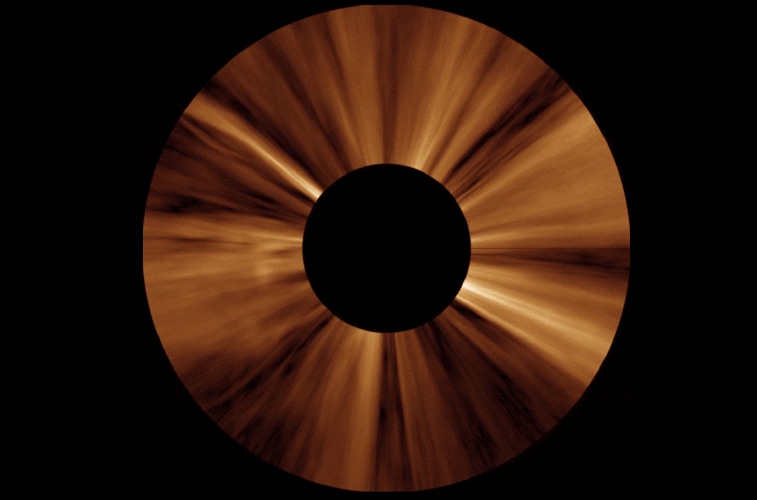

Particularly, they found and imaged finely detailed streamers, blobs and puffs that pop up in the outer corona, a layer of the sun's atmosphere that begins about 1,300 miles (2,100 kilometers) from the sun's surface and extends some 10 million miles (16 million km), according to their study published July 18 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Scientists knew a bit about the structure, or lack thereof, found inside the corona. "Anyone who has seen an eclipse knows that the corona is not homogeneous in the way that Earth's atmosphere is: There are dense regions and rarefied regions all over," said lead study researcher Craig DeForest, a solar physicist at the Southwest Research Institute's branch in Boulder, Colorado. [See Gorgeous Images of the Sun's Corona in Simulations]

And those different densities are driven by the sun's magnetic field, he added. Beyond that low-resolution understanding, however, they were sort of left in the dark.

Until now. "By looking through coronagraphs (ordinary visible-light cameras with special bits of metal in front, to block out direct sunlight), we can see individual structures in the corona," DeForest wrote in an email to Live Science, referring to the COR2 instrument aboard NASA's STEREO-A spacecraft, which orbits the sun between Earth and Venus.

One of the main reasons DeForest and his colleagues observed the relatively fine details inside the corona had to do with the advanced processing they used to eliminate any noise in the data — such as that from the light of background stars — used to create the images. And what they saw was somewhat mind-blowing.

Here's what they found: Once they got rid of the "noise," the team found structures within the corona's streamers — the streams of dense solar wind leaving the sun — that were just 12,500 miles (20,000 km) wide. "When we made the very best measurements we could using the COR2 instrument, eliminating the noise, we found that each bright streamer is made of myriad smaller, fiber-like strands," DeForest said. "Those strands are the 'structure' we talk about in the paper." [During Eclipses, Astronomers Try to Reveal the Secrets of the Solar Wind]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And, DeForest said, those "fibers" could be even smaller, so much so that the instrument couldn't resolve them.

They also found a lot of blobs, and yes, that is a technical word. It was coined in the 1990s by Neil Sheeley, of the Naval Research Laboratory, who saw the relatively small clouds of charged gas and created time-lapse movies of the phenomenon.

"They are tiny (compared to the corona, but large compared to Earth) puffs of plasma that are released by the sun," DeForest said. "They are common enough that you can usually find at least a few in a coronagraph movie, but rare enough that they are usually only in one or two features in the corona."

In this new study, he added, "We showed that the visible ones to date are just the large-scale tail of a wide distribution of them. Blobs, puffs and similar compact dense features are everywhere."

Beyond showing some pretty cool features of the sun's corona, the research could shed light on one of many solar mysteries.

"The outer part of the corona — the transition from the sun's atmosphere to the solar wind that fills the interplanetary void — is almost the last unexplored part of our solar system," DeForest said. "Nobody really knows how the corona disconnects from the sun."

For instance, deep in space, the solar wind can gust in wildly violent storms. But scientists don't know what triggers this "turbulence" in the first place.

If the sun is generating that turbulence, then the resulting complex structures should be visible from the very start of the solar wind's journey. But until now, scientists didn't have a sharp enough view of the corona to know one way or another.

The new view could provide the answers. "What we found is that each bright streamer in the outer corona is made of myriad smaller, fiber-like strands, down to sizes well under one-tenth of the smallest objects we could see before," DeForest said. "That is interesting because it means the outer corona is every bit as weird and inhomogeneous as the inner corona. That, in turn, gives new insight into the big questions of solar physics, like how the solar wind gets accelerated out into the void."

The Parker Solar Probe, which will begin a seven-year mission this month, will probe even deeper into this mystery and others, including why the sun's corona is 300 times hotter than the lower atmosphere, called the photosphere.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.