'Hobbits' Lived on the Same Island As Today's Pygmies, But They Aren't Related

Ever since finding the remains of the "hobbits" — a small-statured species of ancient human — on the island of Flores in Indonesia, scientists have wondered whether the modern Pygmy people who now call the island home were in any way related to them.

Now, researchers have found that the answer is "no," the modern-day Pygmies on Flores are not related to the ancient hobbits, who go by the scientific name Homo floresiensis.

While the genomes of modern Pygmy people on Flores have DNA sequences from other ancient human relatives — the Denisovans and the Neanderthals — they have "no evidence for gene flow with other archaic hominins," the researchers wrote in the study. [Image Gallery: A Real-Life Hobbit - Homo Floresiensis]

Scientists initially discovered the remains of H. floresiensis in 2003 in the Liang Bua cave on Flores, according to a 2004 study in the journal Nature. The modern-day Pygmy people live just a stone's throw away, and consider the cave a sacred place, said study lead researcher Serena Tucci, a postdoctoral fellow of evolutionary biology at Princeton University.

"The cave is a really important part of their life," Tucci told Live Science. "They believe the spirits of their ancestors live in the cave. It's not uncommon to findofferings of food in the cave. It's part of their culture."

After working and getting to know the Pygmies on Flores, the scientists began a collaboration with them — eventually sequencing and analyzing the genomes of 32 adults in an effort to learn more about the Pygmies' genetic history. (To communicate, the scientists worked with two translators — one to translate from English to Indonesian, and another to translate from Indonesian to the local language, Tucci noted.)

However, because scientists haven't been able to isolate DNA found in the ancient bones of H. floresiensis, they weren't able to simply look for chunks of "hobbit" DNA in the modern Pygmies. Rather, they used a new technique — developed in the lab of study co-senior researcher Joshua Akey, a Princeton University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology — that looked for any archaic genetic sequences in the Pygmies' DNA that the researchers couldn't assign to a known ancient human species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that the Flores Pygmies harbor about 0.8 percent Denisovan ancestry and have a little less Neanderthal ancestry than other East Asians do, Tucci said. But there were no chromosomal segments in the Pygmies' genomes that had unknown origins, meaning that the Pygmies don't appear to have any H. floresiensis in their ancestry, the researchers said.

"Genetically, they're not so different from other populations in that part of the world," study co-senior researcher Richard Green, an associate professor of biomolecular engineering at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement.

This finding adds "texture" to our understanding of ancient human species, said Mark Collard, chair of human evolutionary studies and a professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Canada who wasn't involved with the study.

"We seem to be looking at a scenario in which a population of modern humans left Africa around 100,000 to 70,000 years ago and began the process of colonizing Europe and Asia," Collard told Live Science in an email. But while these humans encountered and interbred with the Neanderthals and Denisovans, they did not mate with the hobbits, he said. [Photos: Earliest Known Human Fossils Discovered]

"This implies that the migrating modern humans did not recognize the hobbits as potential mates and likely simply replaced them through direct or indirect competition," Collard said.

Big and small

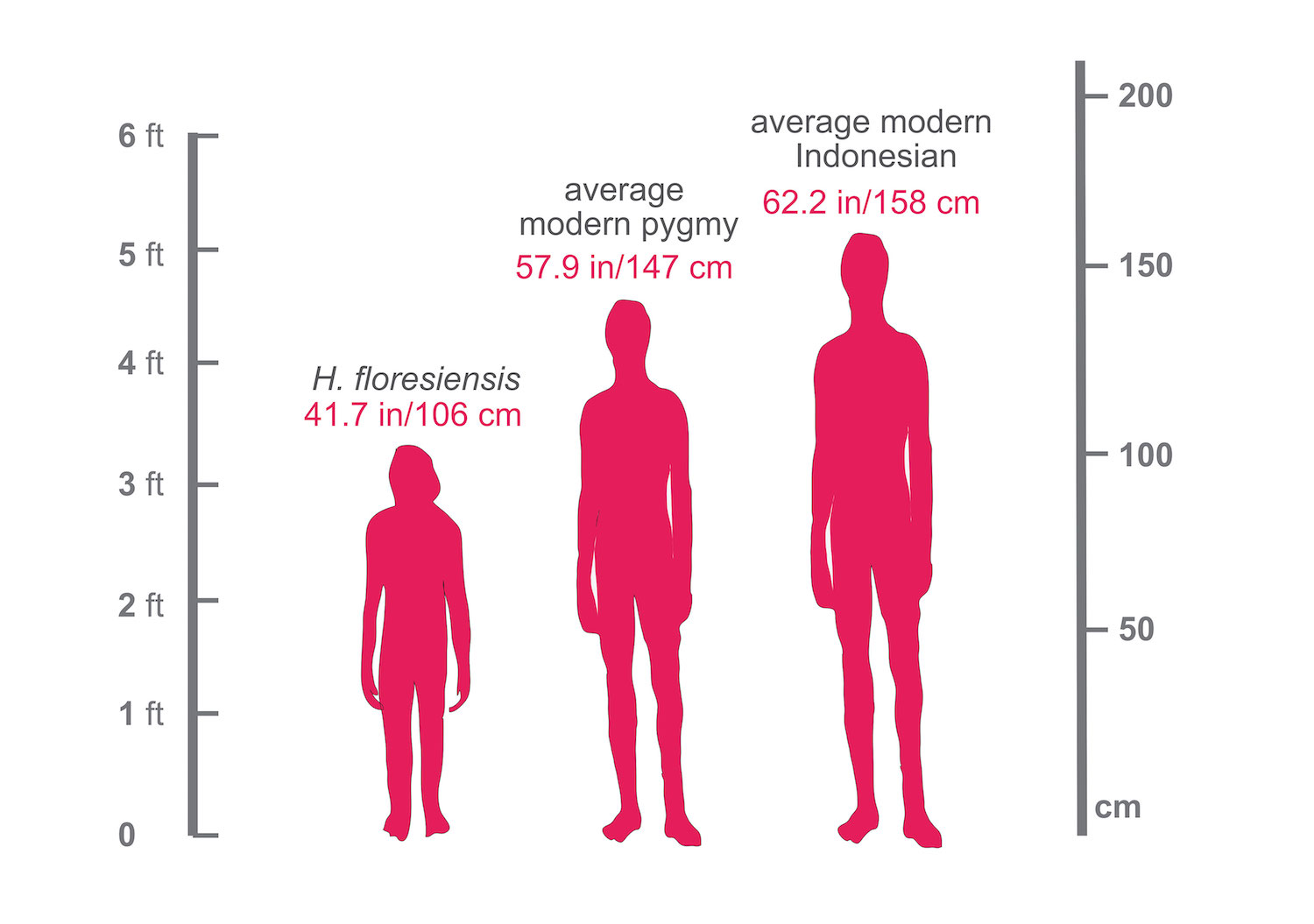

The hobbits were much shorter than today's Pygmies. While H. floresiensis stood an average of 3 feet 5 inches (1.1 meters), Flores Pygmies are about 4 feet 9 inches (1.45 m) tall.

It's possible that both groups became small due to the so-called island effect — when certain animals evolve to be smaller over time (possibly because there is less to eat on an island, so it's advantageous to be small) and other animals evolve to be larger (perhaps because of the lack of predators), Tucci said. For instance, Flores once had dwarf elephants, and the island still supports giant rats (Papagomys armandvillei).

The Pygmies' height does seem to be the result of this short-stature advantage. For example, the research team found that the Pygmies had a high prevalence of genetic variants associated with short height.

In effect, this means that the Pygmies didn't become short because of genes from an archaic hominin. Instead, they likely shrank over time because of selective pressuresin their island environment. "It means that these gene variants were present in a common ancestor of Europeans and the Flores Pygmies," Green said. "They became short by selection acting on this standing variation already present in the population."

Perhaps both the hobbits and the Flores Pygmies experienced "island dwarfing" due to the selective pressures on the island, the researchers said.

"[But] I'm less convinced by this argument," Collard said.

"Paleoanthropologists used to think that the hobbits are descendants of the large-bodied hominin species called Homo erectus, but recent work has challenged that hypothesis and suggested, instead, that the hobbits are the descendants of one of the small-bodied early hominin species," Collard said. "If the latter hypothesis is correct, then we may not be looking at a case of island dwarfing when it comes to the hobbits, at least not with respect to stature."

The study was published online Aug. 2 in the journal Science. The researchers plan to return to Flores to share the results with the Pygmies who live there, Tucci said.

"They were very excited about participating in the research," she said. "We are now working hard to organize a new expedition to bring the results back."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.